ByGone Muncie: 1910 terror attacks in Los Angeles have ties to Ebright Street in Muncie

At precisely 1:07 a.m. Oct. 1, 1910, a massive explosion destroyed the Los Angeles Times Building at the corner of First and Broadway streets. Twenty-one people died, and 100 more were injured.

The night before, an assailant placed a time bomb made of 16 sticks of dynamite in the back alley. The blast ignited barrels of flammable ink and a natural gas pipe, sending the structure ablaze. The Los Angeles Herald reported, “So quickly did the flames spread that the men on the second and third floors were cut off from an avenue of escape and many hurled themselves to the pavement.”

Similar bombs were discovered at the homes of Harrison Otis, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, and Felix Zeehandelaar, the secretary of the city’s Merchants and Manufacturers Association. Both devices were found before they blew — the timers had jammed. The device at Zeehandelaar's house was deactivated and collected as evidence. The bomb at Otis’ estate exploded when the cops tried to disarm it, though thankfully they ran to safety before the blast.

A day later, Los Angeles Mayor George Alexander hired private investigator William Burns to catch the perpetrators. Burns was also working on a similar case for the National Erectors Association, an early 20th century industry consortium of iron and steel companies. He was hired to gather evidence regarding a bombing campaign that targeted facilities of U.S. Steel and its subsidiary, American Bridge.

This period in United States history was marked with intense labor unrest. Poor working conditions, low wages and deadly disasters ignited explosive growth in trade unions. At rallies, strikes, and protests, local governments and industry barons sometimes responded with violence.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, for instance, ended with a hundred people dead. In May 1886, a deadly bombing at a Haymarket Square rally in Chicago resulted in a nationwide crackdown on organized labor. The Homestead Strike of 1892 and the Pullman Strike two years later both ended in brutal violence.

Still, new unions formed, including the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers (IW) in 1896. When labor negotiations failed with American Bridge in 1905, IW union members walked out. The company responded with open shops and strikebreakers. After months without resolution, radical leadership at IW launched a bombing campaign targeting American Bridge factories and open shop construction sites. The goal was to inflict expensive damage.

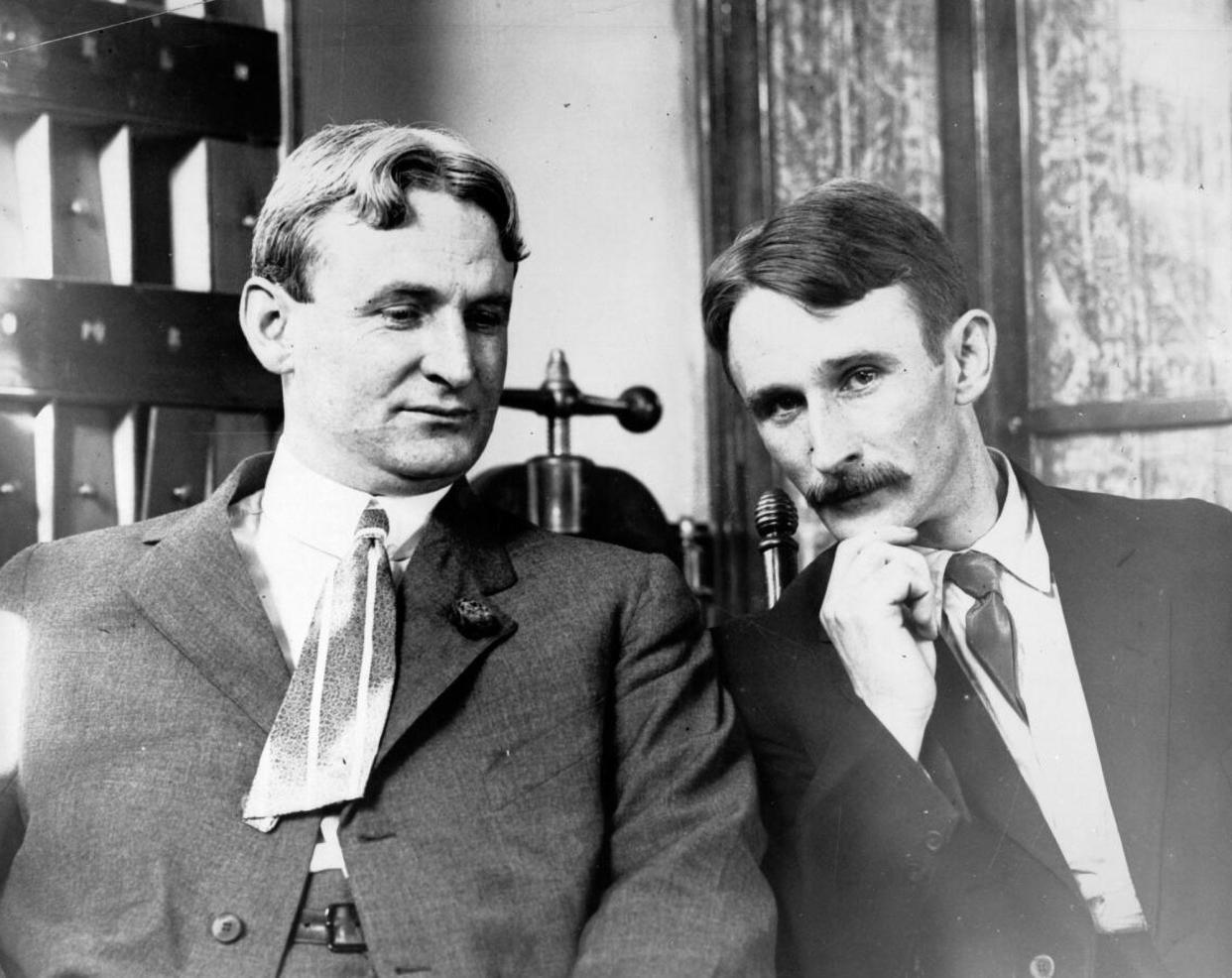

Detective William Burns had gathered info about the bombings from union spies, including Herbert Hockin, a member of the IW’s board of directors. Hockin had procured nitroglycerin for the campaign and managed some of the saboteurs. He worked under orders from IW’s president Frank Ryan and secretary-treasurer J.J. McNamara.

From Hockin, Burns learned that a man named Ortie McManigal planted many of the timebombs.

Detective Burns also suspected that IW was behind the Los Angeles Times’ bombing. California’s big cities had grappled with major labor unrest earlier that summer. The L.A. Times and its vocal publisher were staunchly anti-union through it all. The sentiment was widely shared by the Merchants and Manufacturers Association.

Burns gathered enough evidence to confirm his suspicions. McManigal and J.J.’s brother James McNamara were arrested at a Detroit hotel on April 14, 1911. Detectives found their suitcases packed with clocks and dynamite. A week later, J.J. McNamara was arrested at IW’s headquarters in Indianapolis, located in the American Central Life Building on Monument Circle.

Police found 100 pounds of dynamite in a basement vault. There was enough, according to the Indy Star, “to have wrecked all the surrounding property had it been discharged.” Detectives also raided a barn west of Indy, finding 17 sticks of dynamite and 2 quarts of nitroglycerin.

The bombings resulted in several sensational trials. Both McNamara brothers eventually pled guilty and were sentenced to prison. A federal trial over IW’s bombing campaign in Indianapolis a year later resulted in 38 convictions. Frank Ryan and Herbert Hockin served prison terms, while Ortie McManigal’s sentence was suspended.

McManigal got off because he had turned state's evidence and provided prosecutors with all kinds of juicy info. He had first met James McNamara in December 1909 at the Braun Hotel in Muncie. From McNamara, he learned how timing devices worked. The meeting was arranged by Hockin.

The trio then procured nitroglycerin. Although 1910 was at the end of the gas and oil boom in East Central Indiana, nitro was still widely available just outside of Muncie in the dwindling gas and oil fields. James McNamara had sourced it often from the region.

The bombers falsely presented themselves in the Magic City as "Watson & Sons" of Cleveland, dealers of fine art. In early 1910, they ordered 12 large custom wooden boxes from Delaware County Lumber on Council Street.

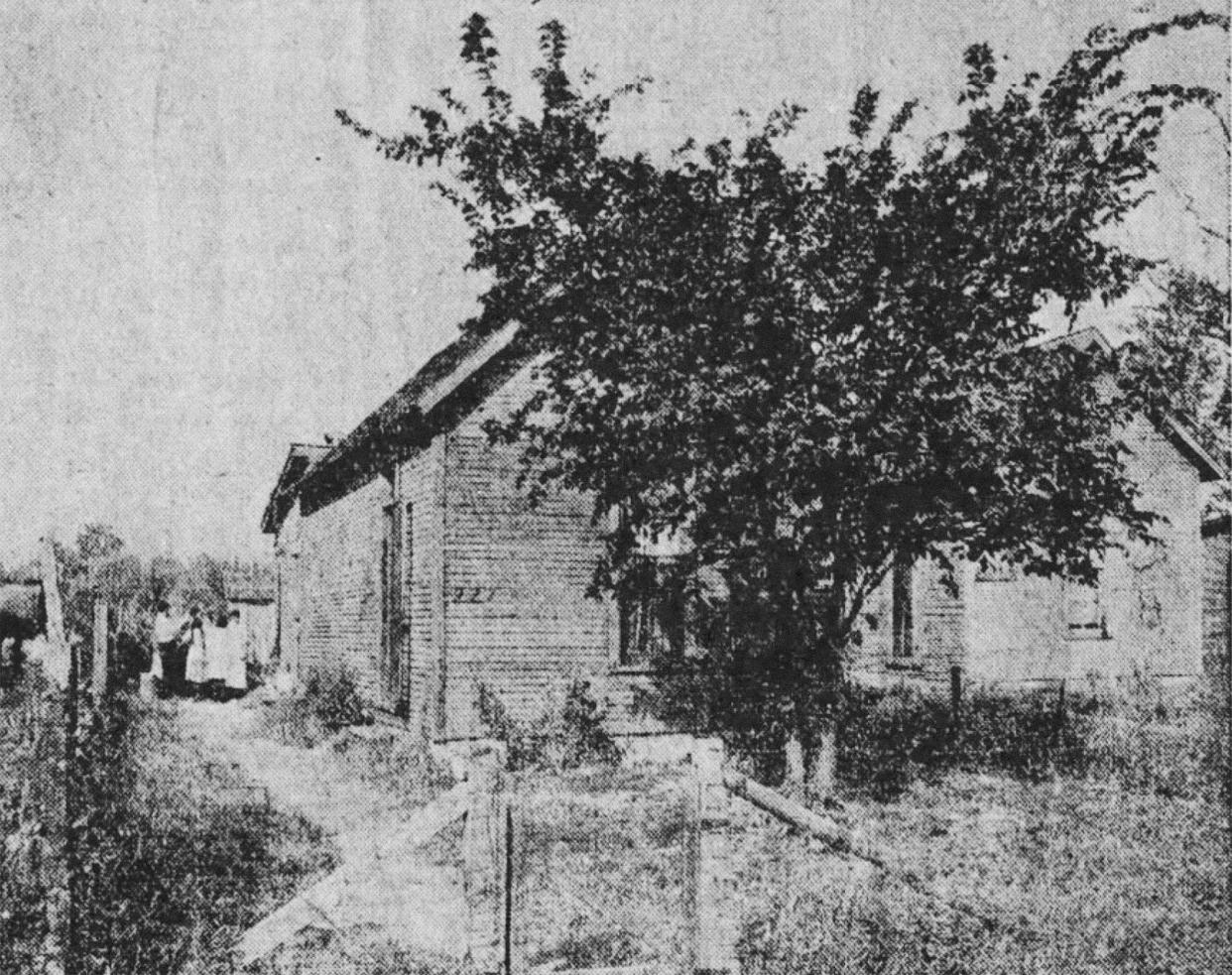

"Watson & Sons" next rented a house at 227 N. Ebright St. in Muncie. The property was owned by Carl Franklin, a local businessman. The saboteurs claimed they “had a surplus of tile on hand” and wanted to temporarily rent the house to store it. Franklin readily agreed when they paid several months' rent in advance.

In spring, McManigal and Hockin attempted to buy a large quantity of nitroglycerin from John Longabough of DuPont Powder in nearby Montpelier. McManigal claimed it was needed to blast out a new quarry. Suspicious, Longabough refused the sale, citing a company policy that mandated customers hire a DuPont employee to handle any detonation.

Undaunted, the bomber found success in Portland, buying 120 quarts of nitroglycerin from M.J. Morehart of Independent Torpedo Co. Morehart’s sales agent met McManigal and McNamara somewhere near DeSoto and transferred the explosives.

A few days later, residents on Ebright Street saw three men “unload several long boxes from a wagon,” according to the Muncie Morning Star. Neighbors later testified that over a few weeks, they witnessed men coming and going from the house with suitcases. After about a month, they were never seen again.

According to the Muncie Evening Press, the nitro was “conveyed in small lots to Indianapolis, where it was stored in a vault at union headquarters and in a barn on a farm on the outskirts of Indianapolis.” About 40 quarts were moved to Rochester, Pennsylvania, and later stolen by Hockin.

The Morning Star concluded that in early 1910, there was enough nitroglycerin in the Ebright Street house to “blow up the entire city of Muncie.” An exaggeration, but one meant to underscore just how devastating things could have been on Muncie’s east end. Investigators found floorboards in the house stained with nitro. They were later treated, cut up and sent to Los Angeles as evidence in the McNamaras’ trial.

The 1910 LA Times Building bombing still ranks as one of the deadliest domestic terror attacks in the United States. If you’re interested in learning more, I recommend Lew Irwin’s 2013 book, “Deadly Times: The 1910 Bombing of the Los Angeles Times and America’s Forgotten Decade of Terror.”

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a senior lecturer of media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: A house on Ebright Street in Muncie tied to 1910 terror attack in LA