Connected Communities' success depends on holding private investors accountable | Opinion

Since March 2023, rents for single-family homes in Cincinnati have raised 8.3% while hourly wages have risen less than 2%. Cincinnati's Connected Communities plan, passed by City Council on Wednesday, seeks to reconcile the gap between rent and income by loosening zoning restrictions that inhibit the construction of middle housing options.

Permitting more duplexes and triplexes in the city will allow for greater density, stabilize rents, and help more Cincinnatians reach the goal of homeownership, according to Mayor Aftab Pureval and city planners − a goal many have been historically barred from as a legacy of racially-restrictive covenants and single-family housing zoning policies.

While the Connected Communities plan might increase the supply of housing in Cincinnati, to pretend as if the zoning overhaul alone will guarantee affordable housing for Cincinnatians is optimistic at best and naïve at worst. For Connected Communities to succeed, it is necessary for the city to tackle the other corroborating factor majorly thwarting housing affordability: private equity investors.

Real estate has long been a component of private equity portfolios, as they are considered stable and profitable investments. Since the 2008 housing crisis, investors have been increasingly focused on turning affordable homes − typically bought by families as starter homes − into lucrative rental properties. Midwestern cities such as Cincinnati, Cleveland and Dayton are particularly attractive to private equity investors because housing prices and rents are lower compared to larger metropolitan areas.

"A big part of the reason Cincinnati has been a particularly attractive market for these kinds of investors is because of how quickly housing prices are rising here. To them, it’s a good investment because they expect that trend to continue − and that is specifically a function of our lack of housing supply," Pureval said in an email to the Enquirer's editorial board.

Private investor purchases drive down homeownership

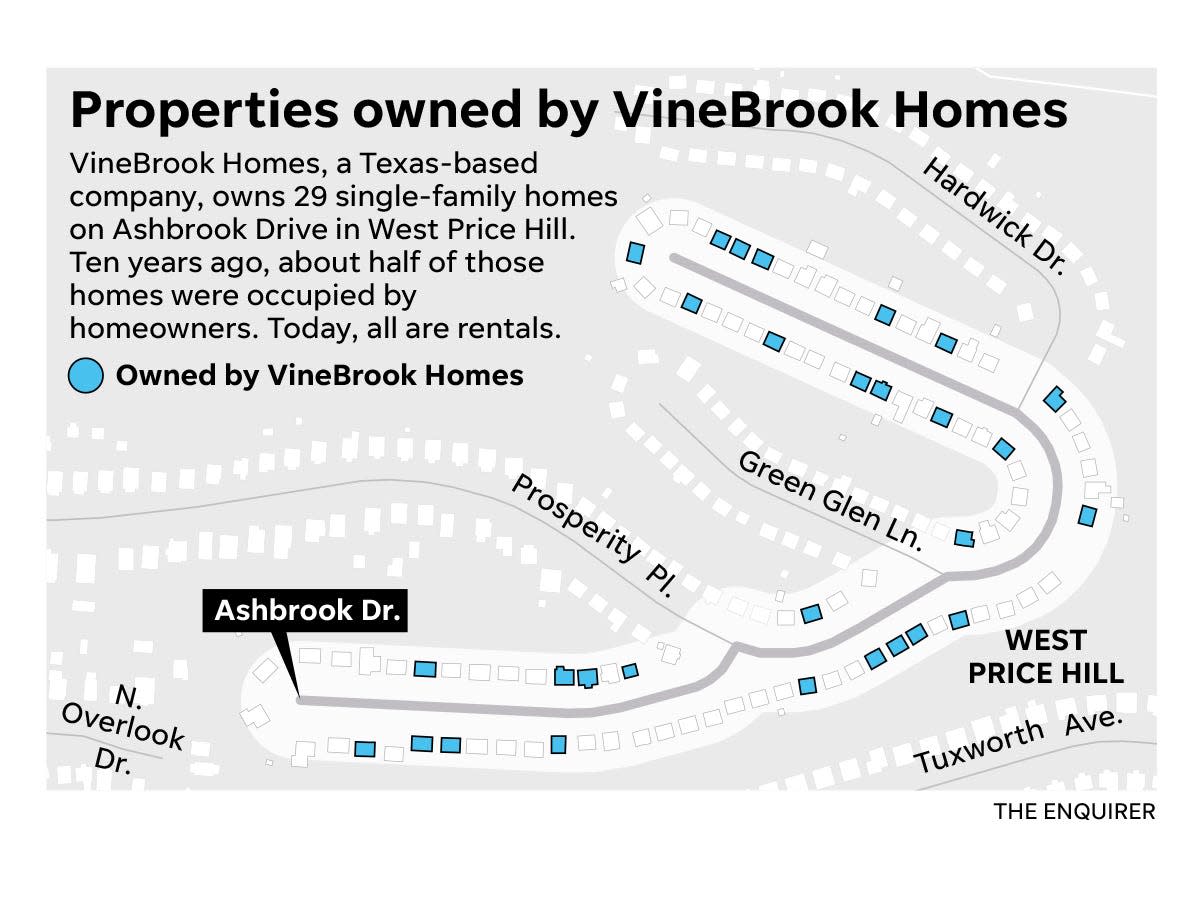

In Cincinnati, nearly 1-in-4 homes bought from 2022-2023 were purchased by private equity companies for an average price of $150,000 each. While these investments have made investment trusts such as Vinebrook Homes and Venture Real Estate Company wealthier, buying up thousands upon thousands of units of affordable housing has kept homeownership a hard-to-achieve goal for many Cincinnatians. With many affordable properties converted into rentals, Cincinnati is among the cities with the lowest homeownership rates, making it incredibly difficult for families to accrue generational wealth.

The rezoning policy put forth by Connected Communities will most likely encourage developers to build duplex and triplex developments that will improve the density and walkability of Cincinnati neighborhoods. At the same time, an increase in housing supply equally offers private equity companies the opportunity to expand their lucrative portfolios, further impairing growth in homeownership.

Private equity's mass-purchasing of affordable housing units might be more palatable if Cincinnati companies addressed the needs of their tenants and complied with ethical housing practices. However, Vinebrook Homes, which owns over 3,000 affordable rental units in the Cincinnati region, has an ongoing lawsuit filed by the city of Cincinnati for claims of public nuisance, civil conspiracy, and multiple violations of the Cincinnati Municipal Code and the Ohio Landlord Tenant Act.

While Vinebrook denies the city's claims as "scapegoating," if private equity landlords are failing to uphold the law and address tenants' needs − as multiple ongoing lawsuits with additional private equity trusts suggest − it is clear that our city cannot continue to let housing units fall into such hands.

In the past, the city government has taken bold measures to counter private equity's attempts to buy up affordable housing. In 2021, the Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority outbid private equity firms to pay $14.5 million for 200 affordable housing units, ensuring that such units would not be needlessly marked up for the sake of corporate profit.

What can Cincinnati do to grow, protect affordable housing?

While the mayor has affirmed his administration keeps "everything on the table" when it comes to issues as crucial as affordable housing, including direct payments to home buyers through programs like ADDI (American Dream Down Payment Initiative), Pureval feels mitigating challenges in the housing market requires change at the system level.

"However, cities are inherently limited when it comes to affecting the housing market through cash − there are only so many resources we can provide directly," Pureval said. "In order to create lasting, positive change, we have to reform our systems."

The problem of trusts buying up affordable housing units is a national issue. In one Cleveland ZIP code alone, private equity owns 70% of homes. In Atlanta, three private equity companies alone own over 11% of the single-family housing in the metro market. There's no question as to why this phenomenon is happening: single-family rentals are really profitable for investors, and there's few disincentives to discourage the extent to which investors outcompete local families for housing options.

"We have been clear in our words and actions that if out-of-town investors plan to buy up properties, neglect them, and raise prices, they will be held accountable," Pureval said.

How does the city plan to hold out-of-town investors accountable? The most viable possibility is through national legislation, which could curb predatory investing on the systemic scale.

The Stop Predatory Investing Act, sponsored by U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and first announced in July 2023, aims to discourage predatory investing across America by ending tax breaks for private equity firms buying affordable housing. This act doesn't target small investors; rather, it specifically prohibits real estate companies with portfolios of 50 houses or more from deducting interest or depreciation if the houses were purchased after the date of the bill's enactment.

While the bill doesn't do much to cut down on private equity's existing market share of single-family homes − investors would still be able to claim deductions on houses bought before the bill's enactment as well as on houses built with Low-Income Housing Tax Credits − it is a step in the right direction to discourage predatory investing practices.

To get more Cincinnatians on board with Connected Communities, a plan that several community councils opposed, city officials should demonstrate their commitment to preventing predatory investing practices. The Port of Greater Cincinnati Authority has demonstrated its commitment financially, and the mayor has previously spoken on the Stop Predatory Investing Act.

In this moment, it is essential to prove to Cincinnatians that the city actually will hold predatory investors accountable − the success of the Connected Communities initiative depends on it.

Meredith Perkins is an intern on the Opinion team at the Enquirer and currently attends Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, studying English and diplomacy. She is a native of Independence, Ky.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Connected Communities doesn't hold out-of-town investors accountable