Contrary to false narratives, KC Royals owner John Sherman is crucial community pillar

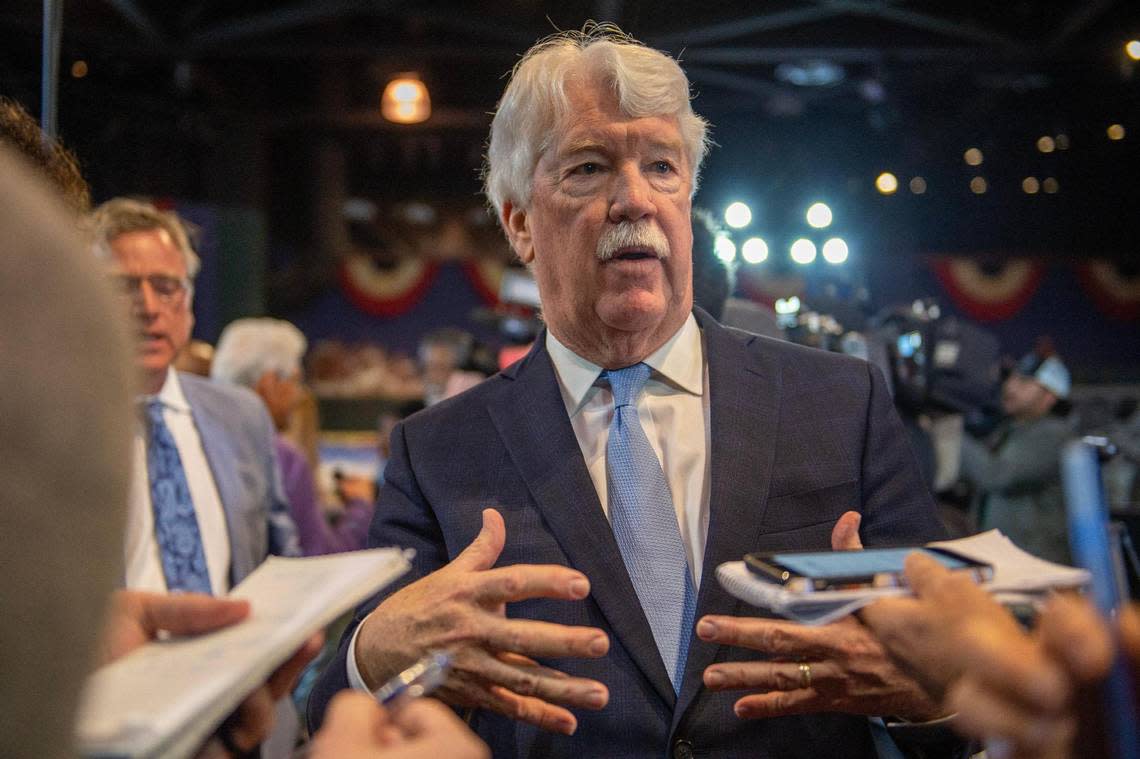

Amid the fevered pitches for and against a proposed 40-year sales tax in Jackson County to help fund construction of a Royals downtown ballpark and a renovation of GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium, those opposed questioned everything from the necessity of the would-be Royals relocation to the uncertainty around key details.

They worried about the implications for the culture of the East Crossroads. And they wondered why any such project shouldn’t be paid for entirely by an ownership group worth billions instead of through taxes affecting those less well-off— a point that should give anyone pause.

Those were all fair concerns, and all part of why the ballot measure in April failed 58% to 42%.

But another aspect of campaigning against the initiative was false and nasty, partly from deliberate distortion and partly by innocent ignorance.

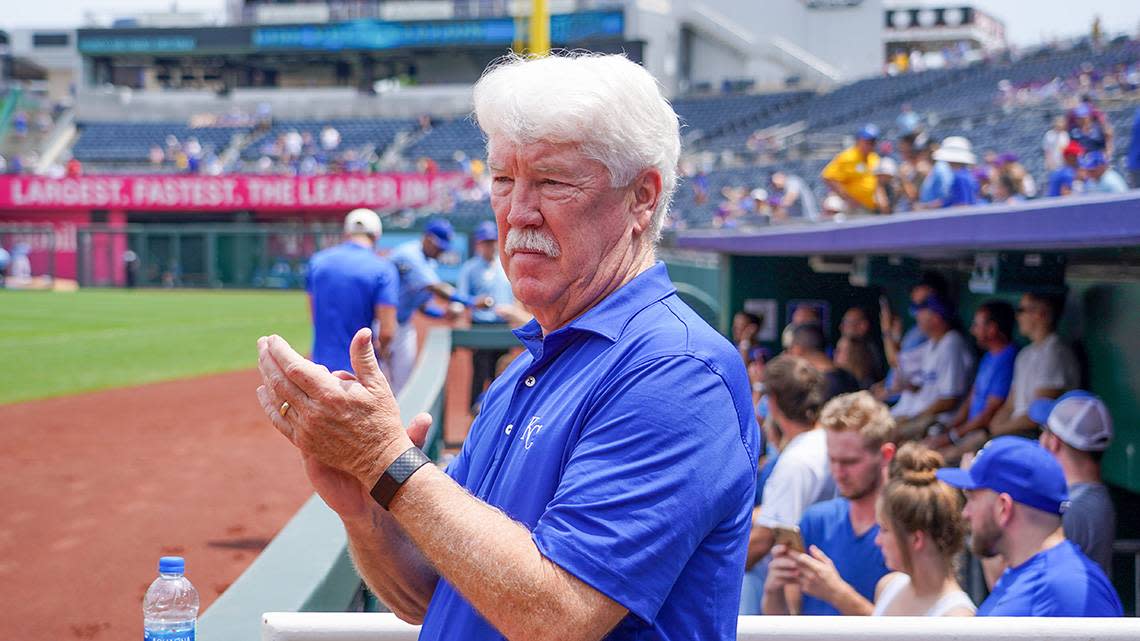

That was the all-too-frequent and absurd villainization of majority owner John Sherman, as if he were a carpetbagger swooping in to exploit Kansas City.

Along the way, I heard from people who thought the 69-year-old Sherman didn’t actually live in the city where he has spent his entire adult life except for a short time in Houston.

During the scrum, some suggested the project was a mere vanity ambition or money grab — a notion that Sherman acknowledges made him “shudder a little bit.”

Maybe most jarring to Sherman, his family and others who know him best, though, was the broader insinuation of all that: that he didn’t really care about Kansas City.

He tried to maintain the perspective of the long game, but …

“It was a political process,” he said, mustering a laugh and adding, “That’s a blood sport.”

With residual damage that lingers — and begs rectifying.

‘Genuine care and concern’

None of that nonsense is true about Sherman, who along with his wife, Marny, has been a vital pillar of the community for decades — particularly through an astounding depth and range of philanthropy and emotional investment in numerous meaningful causes.

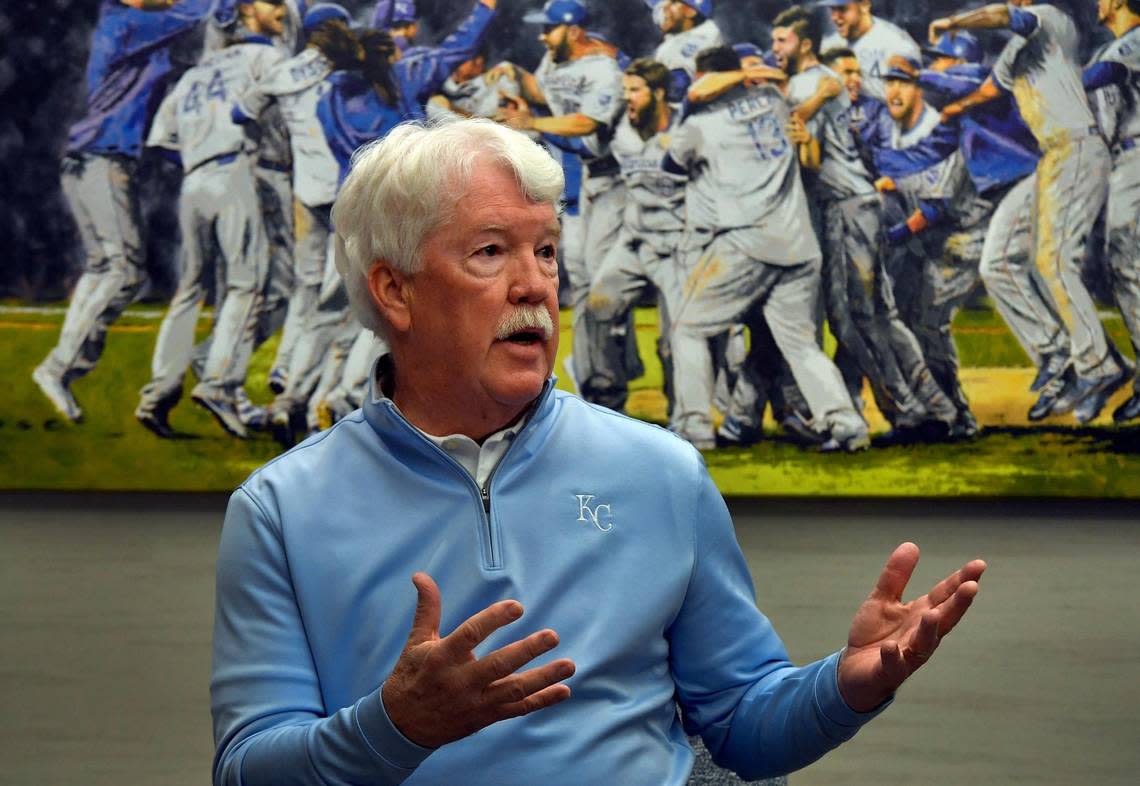

Since his entrepreneurial ventures in the energy business left him financially “rewarded beyond my wildest dreams” in the early 2000s, Sherman has felt a calling to give back and enhance the region through the Sherman Family Foundation and beyond.

If that sounds hokey or too good to be true, it’s demonstrable through raw data, revealing anecdotes and intimately informed opinions such as the stirring one shared by Cristo Rey Kansas City president and CEO Claudia Meyer:

“If it wasn’t for them, we probably wouldn’t exist,” she said. “If it wasn’t for them, our school would not survive.”

Since his early days of fortune “just kind of wandering around with a checkbook” and not quite knowing what to do, Sherman and his wife have bestowed tens of millions of dollars — and countless hours of their time — upon the arts and, especially, toward educational causes.

As noted in his KC Chamber recognition as the 2021 Kansas Citian of the year, his Sherman Family Foundation “contributes about $4 million annually to local nonprofits, with a particular focus on urban education.”

“I’ve always thought of it as where you end up should not be dictated by where you start,” said Sherman, whose first date with his future wife was at a Royals game.

None of which means anyone owed them their vote, Sherman would be the first to say. Or that it establishes some quid pro quo.

Your Guide to KC: Star sports columnist Vahe Gregorian is changing uniforms this spring and summer, acting as a tour guide of sorts to some well-known and hidden gems of Kansas City. Send your ideas to vgregorian@kcstar.com.

That’s why the Shermans have been relatively inconspicuous instead of trumpeting their deeds – an admirable quality that may have hamstrung making the case for a stadium.

“You’ve seen (them) touch so many not-for-profit organizations, whether they’ve done it publicly or behind the scenes,” said Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick. “It’s not like they’re saying, ‘Look at us.’ It’s never been that way.

“It comes from a place of genuine care and concern for making our community better.”

Take it from Meyer, Kendrick and others I spoke with who represent some of our most cherished and/or pivotal institutions, also including Big Slick; Great Jobs KC; the National WWI Museum and Memorial; Operation Breakthrough and the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum.

Those are only a slice of the uniquely Kansas City endeavors enriched by Sherman, who as chairman and CEO of the Royals also has demonstrated a similarly humanitarian commitment to the team.

Case in point: During the pandemic-canceled 2020 minor-league season, he embraced then-general manager Dayton Moore’s espousal of paying minor-leaguers despite being unable to play that year. And he didn’t lay off or furlough any of the team’s employees in that shortened season (the highest-paid employees took temporary pay cuts).

‘They want it to be a better world’

As she pondered the misinformation about the Shermans, Gloria Rudd thought of it as “the sort of conversation you hear when people spout things they heard without any knowledge to back it up.”

Then she thought about the movie “Annie Hall,” and the scene in a line at a movie theater: Woody Allen challenges a blowhard’s interpretation of philosopher Marshall McCluhan by calling in McCluhan himself to correct him.

“I heard what you were saying,” McCluhan says. “You know nothing of my work.”

With a laugh, Rudd said, “How many times do you wish you could do that?”

In essence, this is one of those times to be able to correct the record.

As the mother of actor Paul Rudd and a deeply engaged member of the Big Slick Family Board, Rudd knows something of the work of the Shermans.

They have been key donors, she said, who have offered support in numerous other ways toward their cause of eradicating pediatric cancer. Big Slick Celebrity Weekend this year raised nearly $4 million for Children’s Mercy Hospital and has amassed more than $25 million over the last 15 years.

“They are so gracious, and I can’t sing their praises enough,” Rudd said, later adding that everything they do is for the betterment of the area or people of the area.

At Cristo Rey Kansas City, a donor-funded Catholic college-and-career prep school for the underserved, Meyer is emotional when it comes to the Shermans.

That goes beyond the fact they’ve been major donors since the school’s inception in 2006. Marny Sherman was a founding board member who remains as involved in every facet today as she was then.

It’s about what Meyer called “the amazing human spirit that they bring to our school, the human interest to make things better. They want it to be a better world.”

As Meyer was transitioning into the job and feeling lonely at the top, particularly as a Latina and first female president of the school, she constantly was encouraged by the Shermans.

“They would call and just simply say, ‘Are you OK? What can I do for you? How else can we support you?’” Meyer said, noting, too, that, “when they walk these hallways, what you feel is that they are connected. It is not just publicity, sit here and do my time … They can tell you stories; they can connect back to students they’ve known for many years. …

“They are very authentic and genuine in their relationship with all of us.”

That includes partnership with Sherman’s businesses, including the Royals, to provide work-study jobs — an element Sherman embraces because he believes it helps create generational change.

“So when you ask, what is the impact, they’re not only changing the lives of our students, but changing the lives of families in our community,” Meyer said.

No wonder Meyer has felt angry and hurt over the untrue narratives she encountered during the run-up to the election.

“Every time I had an opportunity to set the record straight,” she said, “I would do it.”

The same goes for CEO Earl Phelan of Great Jobs KC, which provides college scholarships, tuition-free job training and employment assistance for young adults in low-income communities.

“Unfortunately in these times that we’re in, people speak very freely but oftentimes with very few facts or very inaccurate information,” said Phelan, whose relationship with Sherman began when each was on the board of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

The accurate version, he said, is that of an “incredibly generous” benefactor who also has moved Phelan as a great listener and adviser who cares about people getting a chance they might not have otherwise.

“I find them to be very humble and kind of understated in their (giving),” he said. “And maybe that’s why people don’t know about it.”

‘We thought they could use a little love’

As WWI Museum president and CEO Matthew Naylor thinks of the couple, he believes the uniquely American spirit of philanthropy is “beautifully exemplified in the Shermans.”

“My view is that the commitment that the Shermans have to the Royals is an expression of their deep commitment to the overall welfare of Kansas City,” the Australian-born Naylor said.

While they’re “quiet in their extraordinary generosity,” he said, they have been entirely engaged in their capacities on the board. John Sherman served in the past and Marny, whose grandfather served in World War I under Capt. Harry S. Truman’s Battery D, does currently.

Their board service has included diligence in oversight and accountability, Naylor said, while also using that role as a platform to encourage other philanthropists — especially in the museum’s programs for literacy and education.

At the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kendrick has found the Shermans to be equally sincere and stalwart.

Sherman long has been a proponent of the museum, including bringing other members of the Cleveland ownership team there during the years he was a minority owner of the major-league franchise in Ohio.

But he still marvels that Sherman had the presence of mind to call him in November 2019 to let Kendrick know he’d bought the team, and to invite him to a front-row seat for his introductory news conference.

That was right alongside Hall of Famer George Brett and philanthropist Julie Irene Kauffman, the daughter of Royals founder Ewing Kauffman — an oft-cited civic role model for Sherman.

“He acknowledged not only my presence but how important the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum was to him and his entire ownership group,” Kendrick said. “To me, that is a clear indication that (the NLBM) is something that is near and dear to his heart as well.”

While thankful that former Royals owner David Glass had been supportive of the museum, Kendrick noted that it’s now on a different tier because of the man he calls “as unassuming a billionaire as you will ever meet.”

“You can’t have a better ally than John Sherman,” Kendrick said.

Including Sherman’s aid, around the city and in Major League Baseball, in the NLBM’s initiative to raise $25 million to move into a new building.

“He has the ability to influence others to join him. That’s how these projects get supported,” Kendrick said. “That’s how a new Negro Leagues Baseball Museum will ultimately get supported; because of the respect that he has in the world in which he operates.”

All of which is why Kendrick was saddened by how Sherman in some instances was misportrayed — a lamentable turn that inspired Operation Breakthrough president and CEO Mary Esselman and her staff to make cards for the Shermans.

“We thought they could use a little love,” Esselman said.

That was just reciprocating the feeling Operation Breakthrough has enjoyed ever since co-founder Sister Berta Sailer in the mid-2000s called the Shermans and bonded with Marny about love of children and making sure every child had a chance.

Operation Breakthrough’s ability to carry out its mission — “to provide a safe, loving and educational environment for children in poverty and to empower their families through advocacy, emergency aid and education” — nearly doubled with the campaign the Shermans helped lead to expand and build a bridge between buildings on Troost Avenue.

But what moves Esselman as much or more than their financial generosity is their genuineness.

The Shermans were part of every meeting during that campaign, listening and asking questions about the strategy to garner community support. That immersion in the cause stands out about any time Sherman appears on its behalf.

“You would have thought he had my job,” she said. “Because of the way that he spoke about the work, and the details that he was able to share with the group. I mean … who does that? …

“When you think about that, to me that shows what they do is heartfelt. It’s not just obligatory.”

And because it’s from the heart, she added, “They don’t have a need to let everyone know, right? But the people that they impact know it.”

Like the people at the Truman, where an awe-inspiring $29 million renovation was led by Sherman as chairman of its board.

That meant not just funding the lead gift of $2.5 million, as noted on the museum’s honor roll, but setting a tone and leading others aboard.

“When he’s involved in a big project, you don’t just get his check,” outgoing library and museum director Kurt Graham said. “When you say, ‘The Shermans are giving the lead gift on this,’ (many in the community) will jump on board with it. Because they understand that he’s careful and selective about what he does. That carries a lot of weight.”

The money matters, for sure, Graham added. But the reason and inspiration behind the money matters even more.

In this case, it’s about an essential core value: “I’ve heard John speak eloquently about education as a civil right,” Graham said.

And it’s not to have dinners in his honor or his name on a wall. In fact, typical of the Shermans, the World War I theater they funded is named the Donnelly Gallery to honor the grandfather of Marny — who currently is on the board.

While Graham was careful not to suggest any of that should have influenced voting, he reckons the humble and low-key approach factors into why more people didn’t have a better grasp of Sherman’s dedication to the community as one of its greatest contemporary philanthropists.

“I guarantee you that there are organizations all over this city that have anonymous gifts from John and Marny Sherman,” he said.

Whether you wanted the stadium or not, Graham said, “the idea of describing John Sherman as anything other than generous is preposterous.”

He ruefully added, “It’s always easier to make a point when you’ve got a villain, right?”

‘One person’s impact on a community’

There’s much, much more, like the $2 million gift that enabled the purchase of the warehouse in which was built The Rabbit hOle — on whose board Marny Sherman sits.

And John Sherman’s past roles as the chair of the Civic Council of Greater Kansas City and serving on the board of directors of Teach for America Kansas City and their numerous significant contributions to UMKC.

And the Royals Literacy League, a partnership between the Royals, Royals Foundation, Sherman Family Foundation and SchoolSmartKC that Sherman is thrilled about as a platform to inspire children at a crucial age.

“I’m going to overstate this,” Sherman said, “but if you’re not reading at a third-grade level (in third grade), it’s like your life takes two separate directions after that.”

And, and, and ... well, it’s virtually impossible to be comprehensive about all the instrumental roles and dollars and grants the Shermans have given, the time they’ve spent or the events they’ve hosted trying to make Kansas City a better place

When I first spoke with Sherman about philanthropy in the spring of 2022, he alluded to a number of local role models he’s had ... but none more significantly than Kauffman.

“It’s pretty remarkable,” Sherman said then, “one person’s impact on a community.”

The same could be said for the man whose net worth the Los Angeles Times in 2022 reported was $1.25 billion. (The paper said it culled the net worth of individual MLB owners from Forbes, moneyinc.com, Celebrity Net Worth, Bloomberg and Canadian Business.)

Whatever the future might hold for a new baseball stadium in the area — a point that Sherman reiterated when he said all options are in the region, “and we’re going to be the Kansas City Royals 50 years from now, in my view.”

As for specifics, Sherman said there was “nothing material to talk about at this time,” but that he hopes by late this year or early 2025 they’ll be in a position to say a lot more about it.

“We want a good investment long-term, don’t get me wrong,” he said. “But it has to be about the community and doing the right thing.”

That may or may not entail another vote. And if it does, the burden of proof will remain on the Royals to make their case more clearly and convincingly on what would be a very personal choice.

Just don’t base it on the deceptive myth that Sherman isn’t deeply devoted to Kansas City.