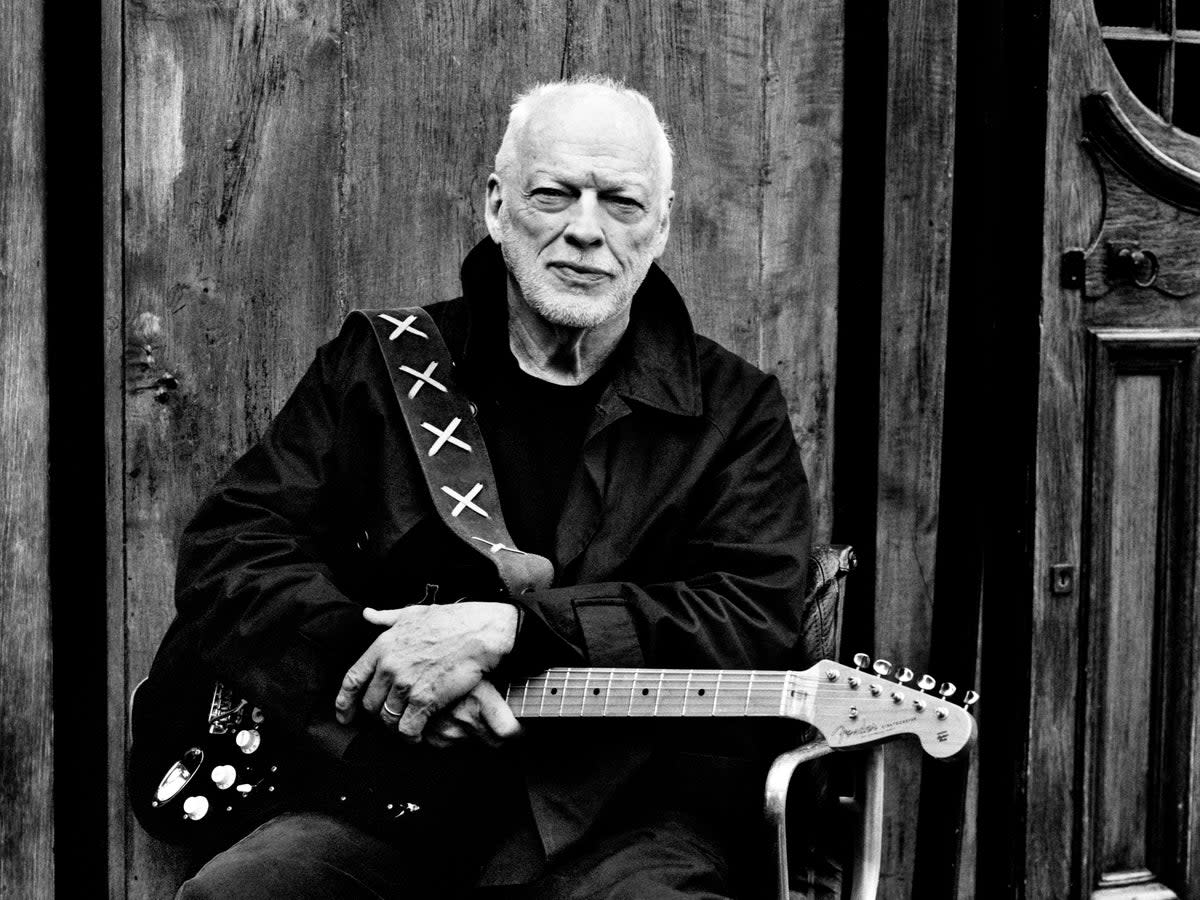

David Gilmour review, Luck and Strange: Graceful ruminations on love and mortality

“Is it wonder or despair that bends my knee?” asks Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour on his fifth solo album, Luck and Strange. Although those lyrics were actually written by his wife, the author Polly Samson. So perhaps she knows best when she later adds that it’s really “desire” that crumples the former Pink Floyd guitarist into submission. At 78, he can still drip hi-def liquid mercury from his fretboard. Even when – as here – he’s plucking and sliding through a series of thoughtful, mid-tempo tracks unlikely to snag the attention of new listeners.

Old fans get to bathe in that silver sound for the first 91 seconds of the record before Gilmour slips into some more low-fi, bluesy grooves. The title track is a swampy number that sees him gracefully acknowledging his privilege, instead of snarking at younger generations like many of his peers. Born in 1946, the middle-class son of a Cambridge University zoology lecturer and a film editor, he owns that this was “was a fine time to be born/ De-mob happy street and free milk for us all.” The lament of his guitar work adds depth to his familiar dry, slate-grey vocals, as he prays that the relative peace and prosperity of the late-20th century wasn’t just a “one-off golden age”.

Stadium-scaled themes of mortality and social commentary have long saturated the Pink Floyd package. Gilmour joined the band as a mental health crisis saw founder Syd Barrett fading out of it, and they hymned his departure on both The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and (Gilmour’s favourite of their albums) Wish You Were Here (1975). Luck and Strange slots neatly into that tradition, featuring a soft drizzle of synths by Pink Floyd’s late keyboardist Richard Wright, recorded in 2007 before he died in 2008.

A combination of personal and political differences mean that Gilmour hasn’t played with Floyd’s other solo artist, Roger Waters, since 2011. In a recent interview with The Independent, he responded to the prospect of a reunion involving both him and Waters with an unequivocal “no”. But the weight of all this weird history infuses the way Gilmour pushes through weariness to sceptical optimism today. In 2019, he auctioned more than 120 of his guitars (including his famous Fender 0001 “Black Strat”) and gave the $21m proceeds proceeds to the environmental charity ClientEarth.

This is an attitude reflected on “The Piper’s Call”, which sees Gilmour sighing that the “spoils of fame” sit uneasily on the conscience. The sonic mood lifts and loosens with steel pans, djembe and Spanish guitar. The pace picks up (aided by a jaunty little cowbell) as the guitarist notes his new “carpe diem attitude” means leaving the cash and drugs behind.

Producer Charlie Andrew (best known for his work with rock trio Alt-J) helps bring some lighter touches into the Gilmoursphere. A harp skims like sunshine over the murky synth waters of instrumental “Vita Brevis” and the tracks are buoyed elsewhere by strings and choir. His youngest daughter, Romany, brings breathy-sweet ease to her lead vocals on “Between Two Points” as she breezes through lines about “rolling with the punches” and letting “the lifeblood bleed from you”.

There’s a little trip-hop shrug swaggering through her youthful weltanschauung, although her dad sounds rejuvenated in a drowsy way on the ballad “Sing” as he croons: “Darling don’t make the tea/ Stay and snooze here with me.” It’s a cosy reflection on ageing love (and one that made me smile, as I recall that Gilmour is the only A-list interviewee I’ve ever seen washing up our tea cups during the chat).

Luck and Strange ends with the thump of a slow’n’steady heartbeat, providing a counterbalance to the panic-attack pulse heard on The Dark Side of the Moon. “Yes, I have ghosts,” sings Gilmour, “and they dance by the moon.” A splashy concert piano-style solo brings the cold drama before the bass and guitar lock into a companionable groove, and the classical guitar thaws old fears into acceptance. Floyd used to sing that “hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way”, but Gilmour sounds happier than that. The darkening days “flow like honey”, he says. All ageing Floydies will find succour here.