‘Did the best that I could:’ Andrew Young reflects on fight for civil rights with MLK

Andrew Young grew up around white folks in a racially segregated New Orleans.

Blocks from his cajun home on Canal Street, there were Italian bars, Irish grocery stores and even a building displaying a swastika in front. That’s where he had to catch the bus to school.

As he navigated his commute, Young would remember advice from his father, which he held onto decades later when he fought for civil rights.

“You understand this because you know that God created [from] one blood all the nations of the world,” he recalled his father telling him. “They don’t want to believe that, but that’s their problem with God. That ain’t your problem, and you don’t need to try to educate them. Just show them respect.”

The civil rights leader discussed his life’s work — as well as “The Many Lives of Andrew Young,” a book profiling him — in a conversation with the Miami Herald’s Jacqueline Charles at the Historic Hampton House in Brownsville on Sunday afternoon. Springing from their seats, the audience clapped as they honored the 90-year-old being assisted onto the stage.

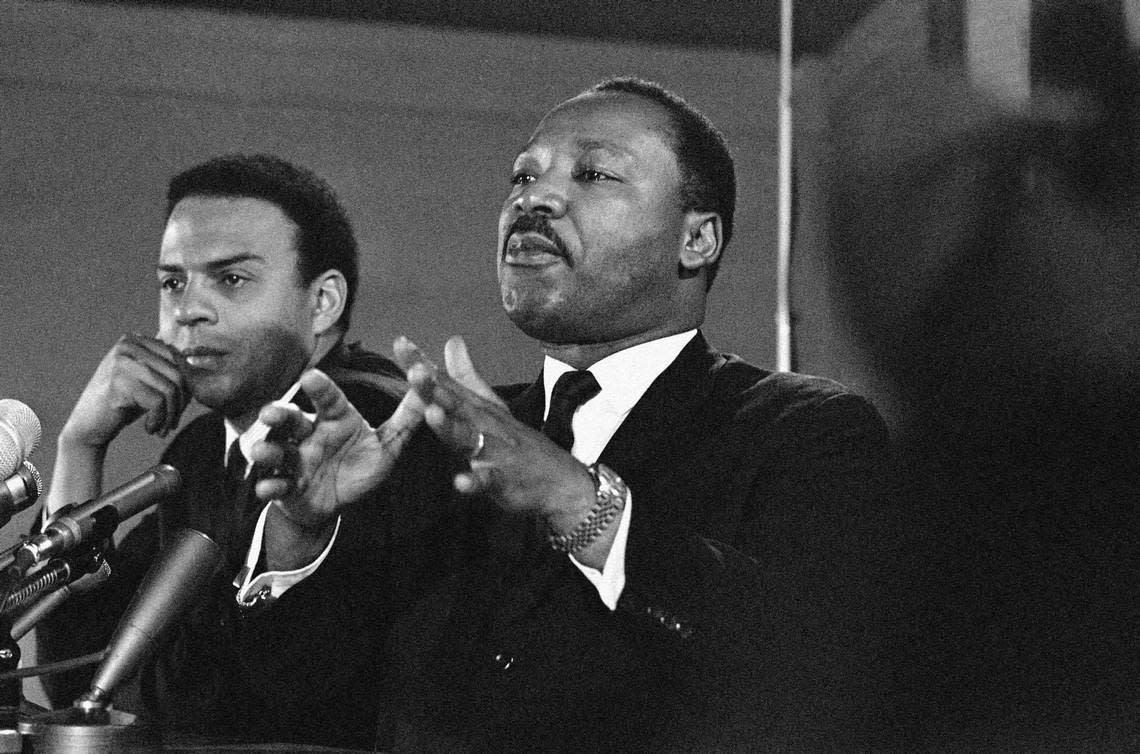

Early into the civil rights movement, the New Orleans native was a pastor — and a confidant to Martin Luther King Jr. Throughout the 1960’s, Young demanded civil rights, organizing marches in Birmingham, St. Augustine, Selma and Atlanta. Despite being jailed several times for protesting, his efforts helped push for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965.

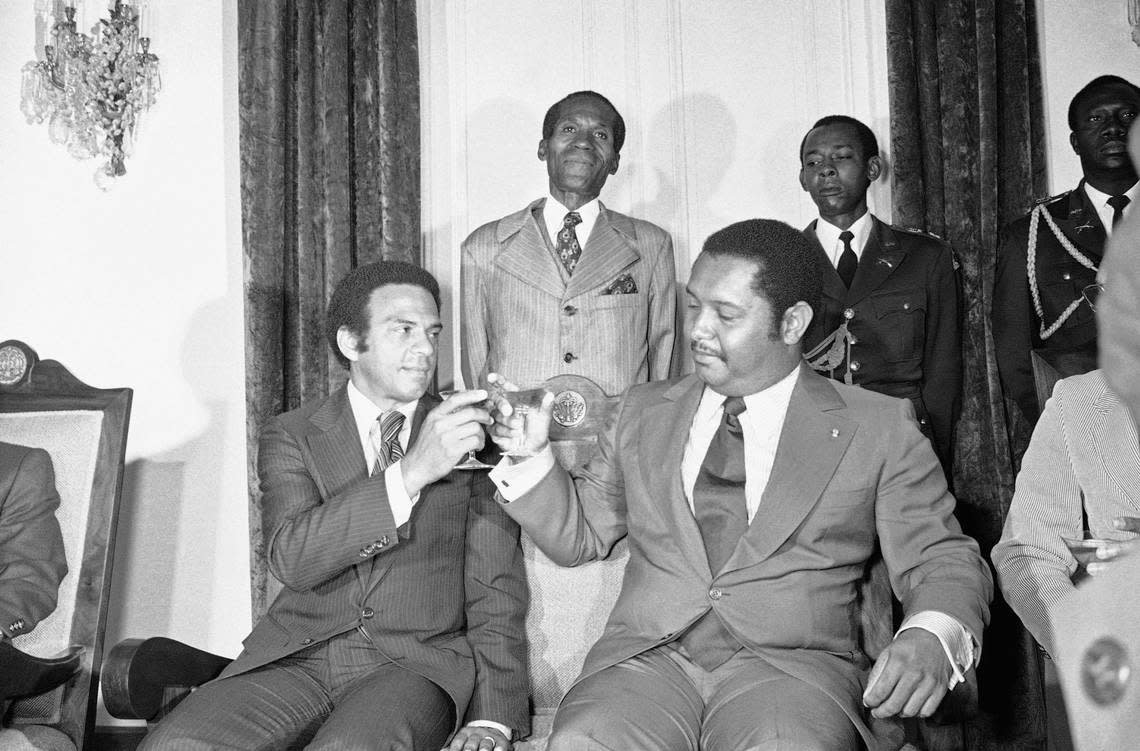

Young, then a U.S. Representative, was appointed to the UN Ambassador role in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter and became the first African American to serve in that office. He was elected as mayor of Atlanta for two terms through the 1980s. Since leaving politics, he’s focused his efforts on the Andrew Young Foundation, which is dedicated to education, health, leadership and human rights around the world.

“I don’t know what my purpose is, and I don’t give a damn,” he quipped as he reflected on his career. “But I’m going to do what the spirit says to do one day at a time.”

Young recounted how he and King connected at Talladega College in 1957. Their relationship blossomed over the years, with them at first only discussing their children and later becoming trusted associates, Young even answering letters for King.

“He kept wondering how I knew what he wanted to say [in the letters],” Young said. “I said ‘I listened to you. When you talk, I hear what you say and I know what you’re trying to do…’”

Young also looked back at the protests and boycotts they organized during the civil rights movement; the violence, beatings and bombings the community faced daily — and how they coped with it all.

“[King] said everything embarrassing that he could think about you,” Young said. “Before you knew it, we were all laughing. And we were all laughing at our own death.”

The Black community in the U.S. has grappled with a pervasive history of injustice through resiliency and persevering amid all odds. Young said he now sees steps toward justice in an era when killings of unarmed African Americans by police officers are exposed to all via social media.

“There was a whole lot of Black folks doing a whole lot of things to bring about justice that we didn’t know the names of,” Young said of people killed and beaten in the ‘60s.

Yet Young doesn’t stress his legacy. Despite his life-long efforts, he doesn’t even care about it. He’s content knowing that he made the world a bit more equitable than when he came into it.

“I did the best that I could with what I had.”