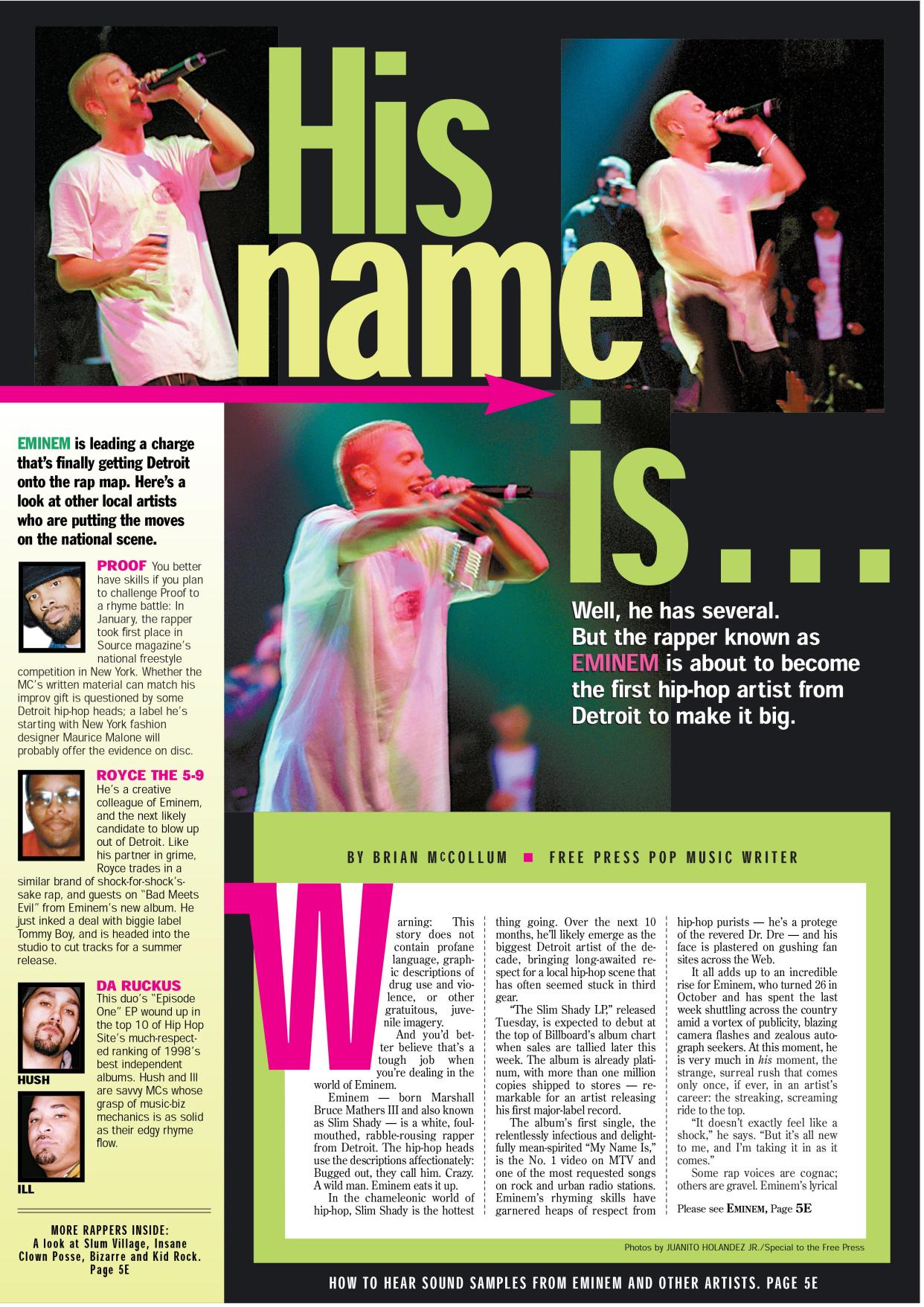

From the Free Press archives: Eminem introduces the world to Slim Shady in 1999

As Eminem prepares to release his 12th studio album, "The Death of Slim Shady (Coup de Grâce)," set to arrive early Friday morning, we've pulled a page from the Detroit Free Press archives and the early Slim Shady days.

In February 1999, the wider world got its introduction to Eminem, following months of growing buzz in the hip-hop underground in Detroit and beyond.

More: Eminem joined by Big Sean, BabyTron on new song 'Tobey' as ‘Slim Shady’ release set

The rapper spoke at length with Free Press music writer Brian McCollum as "The Slim Shady LP" arrived amid much fanfare (and many furrowed brows), helping launch a career that would make him America's top-selling artist the following decade.

Here's that cover story:

~~~~~

HIS NAME IS ...WELL, HE HAS SEVERAL. BUT THE RAPPER KNOWN AS EMINEM IS ABOUT TO BECOME THEFIRST HIP-HOP ARTIST FROM DETROIT TO MAKE IT BIG

By Brian McCollum, Detroit Free Press, Feb. 28, 1999

Warning: This story does not contain profane language, graphic descriptions of drug use and violence, or other gratuitous, juvenile imagery.

And you'd better believe that's a tough job when you're dealing in the world of Eminem.

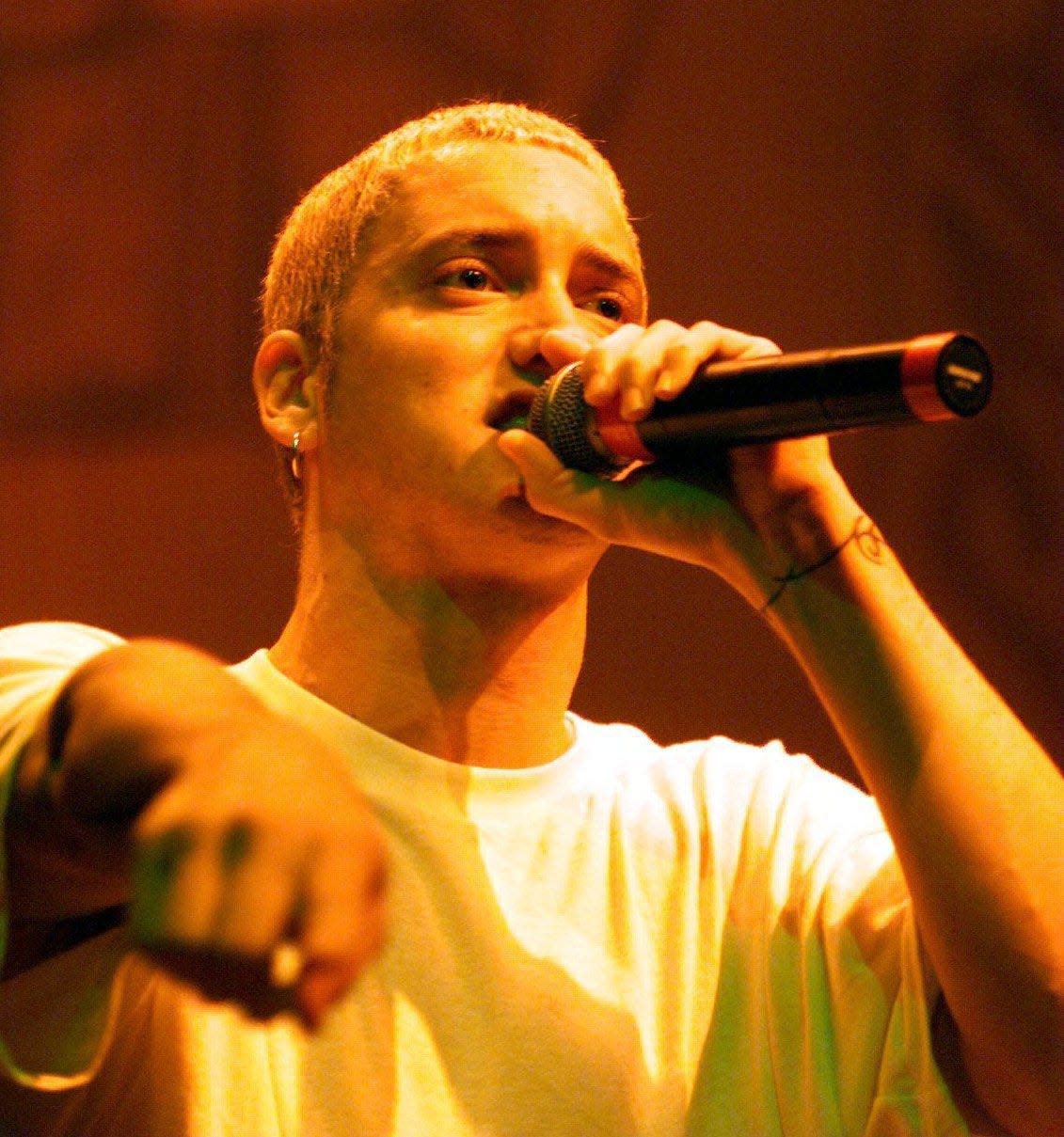

Eminem — born Marshall Bruce Mathers III and also known as Slim Shady — is a white, foul-mouthed, rabble-rousing rapper from Detroit. The hip-hop heads use the descriptions affectionately: Bugged out, they call him. Crazy. A wild man. Eminem eats it up.

In the chameleonic world of hip-hop, Slim Shady is the hottest thing going. Over the next 10 months, he'll likely emerge as the biggest Detroit artist of the decade, bringing long-awaited respect for a local hip-hop scene that has often seemed stuck in third gear.

"The Slim Shady LP," released Tuesday, is expected to debut at the top of Billboard's album chart when sales are tallied later this week. The album is already platinum, with more than one million copies shipped to stores — remarkable for an artist releasing his first major-label record.

The album's first single, the relentlessly infectious and delightfully mean-spirited "My Name Is," is the No. 1 video on MTV and one of the most requested songs on rock and urban radio stations. Eminem's rhyming skills have garnered heaps of respect from hip-hop purists — he's a protege of the revered Dr. Dre — and his face is plastered on gushing fan sites across the Web.

It all adds up to an incredible rise for Eminem, who turned 26 in October and has spent the last week shuttling across the country amid a vortex of publicity, blazing camera flashes and zealous autograph seekers. At this moment, he is very much in his moment, the strange, surreal rush that comes only once, if ever, in an artist's career: the streaking, screaming ride to the top.

"It doesn't exactly feel like a shock," he says. "But it's all new to me, and I'm taking it in as it comes."

Some rap voices are cognac; others are gravel. Eminem's lyrical flow is reedy, pungent, acidic, his oddly accented lines and internal rhyming deftly delivered with ear-catching flair.

The rhymes are Tipper Gore's nightmare, and most can't be printed here. But this isn't just your standard hard-core hip-hop, defined by its gritty imagery and street-tough boasts.

No, this stuff flows from a tradition that's all Detroit: the tried-and-true school of schlocky shock, the wink-and-nod allure of horror film violence. Eminem calls himself white trash on record. His protagonists are comic-book caricatures, murdering their wives, popping pills, dosing their dates with psychedelic mushrooms. They "slap Garth Brooks out of his rhinestone shirt" and "beat up Foghorn Leghorn with an acorn."

It worked for hometowners Alice Cooper and Insane Clown Posse — a group Eminem despises — and it made Kiss beloved here.

Eminem has already heard the beefs about his content. And he says people should relax.

"A lot of my rhymes are just to get chuckles out of people," he says. "Anybody with half a brain is going to be able to tell when I'm joking and when I'm serious."

Rhythm and humor

He is, first and foremost, a perfectionist.

Always has been, friends say. They remember Em scrapping four dozen takes of a single line before nailing the one he liked. Giving away his cassettes to anybody who would hold their hand out, and even to some who wouldn't. Phoning and pressing and pleading to get on the air at WHYT-FM, earlier in the decade when it had an urban format, for the station's "Friday Night Raw," a freestyle-rap showcase.

Show host Lisa Orlando, now at WDRQ-FM (93.1), says he became "one of the premier rappers on the show."

"He had really good rhythm," she recalls. "A lot of times, you look at a young guy and — especially back in the day — their thing is very aggressive and violent. He was more of the roots of hip-hop: very rhythmic, very humorous at times. He had skills."

Eminem says he grew up with his fingers on hip-hop's standard stylistic touchstones: LL Cool J, Run-D.M.C., the Beastie Boys, 3rd Bass.

"I was just a fan of rap," he says, "trying to do what everybody else was doing."

He was still in that mode when he linked up with the Bass Brothers — Detroit production duo Mark and Jeff Bass — to begin recording tracks soon after they'd heard him on "Friday Night Raw." The result: 1996's "Infinite" album, released independently.

"But I was too young, man," Eminem says. "I didn't know what I was doing. I was rhyming. I knew I could put words together. But I just didn't have the whole formula yet."

He remembers when it clicked, when the creative mission became clear. "Infinite" had just come out, and he wasn't thrilled by the feedback.

"I caught a lot of flak: 'You're trying to sound like Nas. You're trying to sound like AZ. You're trying to sound like somebody from New York,'" he remembers. "'And you're white. You shouldn't rap. You should go into rock 'n' roll. Why don't you try alternative? Blah blah blah.'

"That started pissing me off. And I started releasing that anger in the songs. That's when I found myself."

Next up: 1997's "The Slim Shady EP," featuring many of the same songs that would later be recut for the LP — songs, Eminem says, that finally "brought more of my personality in."

He worked the record locally as a regular performer at weeknight showcases in dingy clubs and a frequent guest on others' albums as his reputation grew. With the help of the Internet and hip-hop's tight underground network, the buzz grew. Eminem had a legitimate gimmick, they said, and the skills to back it up.

Still, he became discouraged by the cold shoulder he felt he was getting from Detroit radio and from the big labels, and when he headed west early last year to hunt for a record deal, he was almost ready to give up on the business.

"We were giving one last crack at it when we came to LA," he says. "We had the 'Slim Shady EP' with us, making one last shot. I said, 'If this doesn't work, I'm done.' "

But it worked. Dr. Dre, the former N.W.A. rapper who had become the biggest producer in gangsta rap, had caught the underground buzz on Slim Shady. He'd heard the EP, with its lurid hyperbole and incisive put-downs, knew that Eminem had snagged runner-up at a national freestyle contest in 1997.

Detroit rapper and Eminem friend Bizarre remembers the phone call.

"He was missing for three weeks. Nowhere to be found," the rapper recalls. "Then he just up and called out of the blue: 'Yo, man, I just signed with Doc-tor DRE! He's got this fresh condo out here; you got to see it . . .!' "

It didn't take long for word to seep onto the Detroit streets: That skinny white kid had hooked up with the most important hip-hop producer of the decade. Their first collaboration — with Eminem on the mike and the veteran behind the production console — would be released on Dre's Aftermath Entertainment, a subsidiary of mammoth Interscope Records.

And here it is, "The Slim Shady LP," with three tracks produced by Dre and a batch produced by old comrades the Bass Brothers.

"Dre's got my back, and I got his, too," Eminem says. "We got a blood marriage, so to speak. Dre saved my life, in a way, and I want to return that favor."

Painfully honest

"My father? I never knew him," says Eminem. "Never even seen a picture of him."

Marshall Mathers was born in Kansas City and shuttled during his early years between Missouri and his grandmother's home in Warren. At 11, he and his mother settled in Detroit.

"We just kept moving back and forth because my mother never had a job," he says, warming up to the story. "We kept getting kicked out of every house we were in."

Mathers claims his mother had other personal problems, and he addresses them on the album. She's heard the tracks and doesn't like some of the references.

"Even though I say it in a joking kind of way, I think it hits home with her," he says.

Growing up, Eminem says, wasn't easy; getting into trouble was.

"Even a lot of my comical lines, there's truth to them," he says. "There's a part of me that's venting, venting over my childhood. I revert back to a lot of that stuff on the album, stuff that happened to me. I make jokes about myself, the way I was raised, things I did."

It's that sort of lyrical honesty, say Detroit hip-hop scenesters, that gave Eminem valuable street integrity and helped the white rapper gain a foothold in a predominantly black arena — a world where Vanilla Ice had damaged Caucasian credibility for years.

"Any true hip-hop person — somebody into the music — doesn't look at his color," says Ronke (Keez) Ciers, who owns the Eastside Music record store in Detroit. "His lyrics are masterful. The shock value is incredible. Eminem is a true hip-hopper trying to do his thing. (His color) "didn't matter back then, and it shouldn't matter now."

"None of the race issues matter at all to me," Dr. Dre told MTV last week. "It doesn't matter. I just care about the talent."

Still, Eminem says, being white didn't always help the cause early on; area radio stations and record stores often spurned his stuff. He says outside of Detroit's purist hip-hop underground — where "they always respected me, man" — trying to take care of business was hampered by pettiness on the local music scene.

"It's like crabs in a bucket, and everybody's trying to fight to get their way to the top, and pulling the next one down," he says. "I had any excuse in the book thrown at me — from being white to I can't rhyme or I'm biting someone else's style, this or that. Any excuse to dis me, I got."

Folks might be a little more supportive these days. By design or not, Eminem has opened doors for a hip-hop scene that has long had trouble getting its legs. In label offices on both coasts, "Detroit" has become a buzzword.

"He'll be the first hip-hop artist out of Detroit to go platinum," says Eastside Music's Ciers. "We're just happy somebody from Detroit finally reached that status."

Contact Detroit Free Press music writer Brian McCollum: 313-223-4450 or bmccollum@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: From the archives: Eminem introduces the world to Slim Shady in 1999