New immigration policy is too little, too late for families who've experienced pain of deportation

MANITOWOC – For Jennifer Estrada, an announcement from the White House that thousands of undocumented immigrants could be shielded from deportation was bittersweet.

The executive action, which President Joe Biden took on Tuesday, will allow undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens to apply for permanent resident status without leaving the country, provide they meet certain criteria.

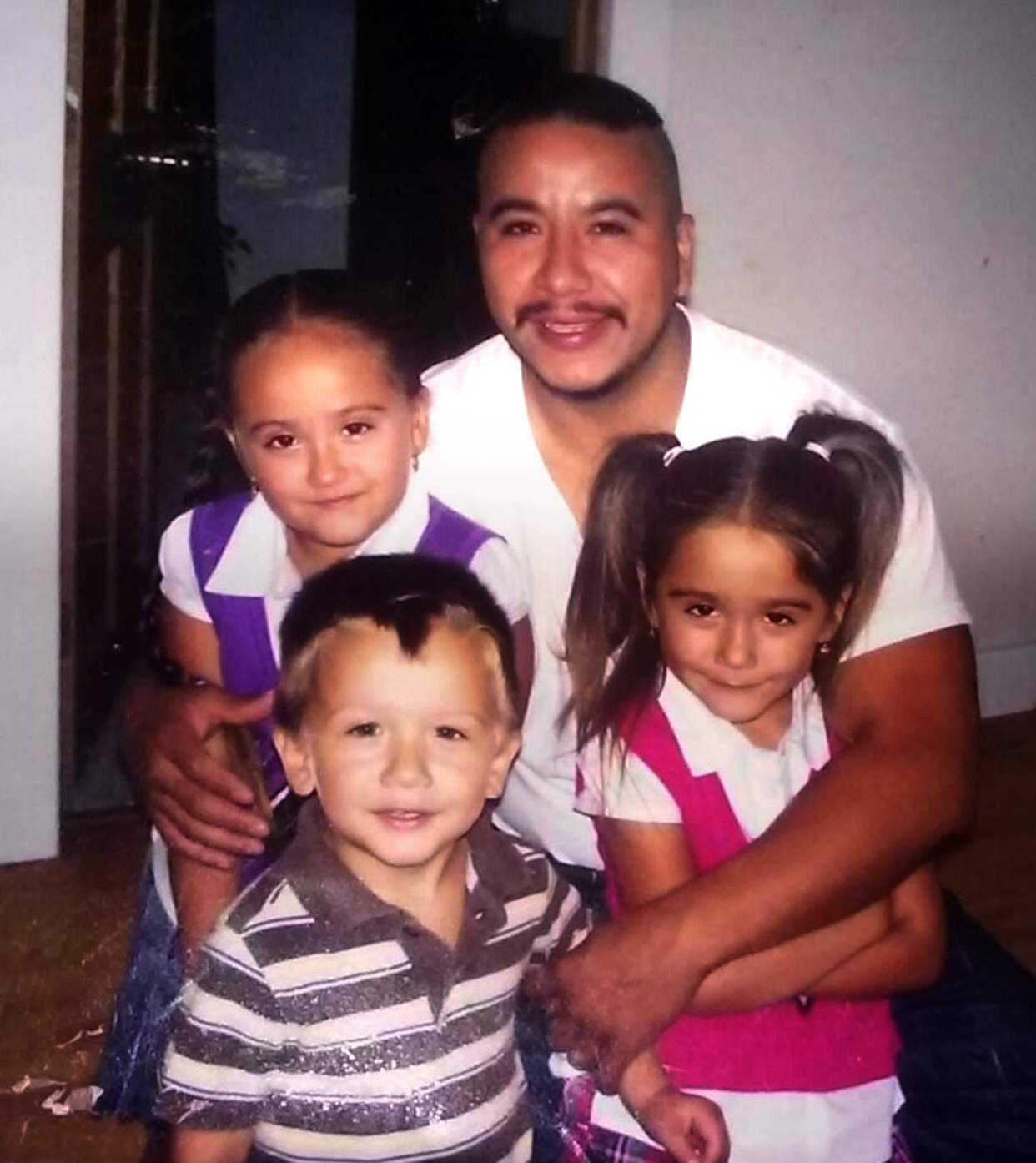

But the change in immigration policy will come as too little, too late, for Estrada. Her husband, Jaime Martinez, was deported to Mexico in 2012. The couple had four young children and Estrada, whose last name then was Martinez, was soon pregnant with their fifth child.

A U.S. citizen, she went to Mexico to be with her husband and not have their family separated. They were together again for around five months.

“Our decision was to essentially move there,” she said, but the level of violence from drug cartels terrorizing her husband’s community not far from Mexico City was unbearable.

“I was playing with my children outside the back of the house when two ladies next door were decapitated in front of us. The cartel had come looking for their husbands, and when they couldn’t find them, they sent a message to the wives,” Estrada said.

“There was no way I was going to raise my children in that environment. They wouldn’t survive,” she added.

The deportation of Martinez caused quite a stir in Manitowoc, a city of around 34,000 in northeast Wisconsin. His supporters held a candlelight vigil and wrote letters of support for prosecutional discretion in his case, according to a 2012 Journal Sentinel article.

"He poses no threat to public safety or national security, and he's a person with strong ties to the community," his attorney, Stacy Taeuber, said at the time.

"Why spend our tax dollars to deport this man and destroy this family?" she said.

The Journal Sentinel reported that Martinez was charged with disorderly conduct after he and Jennifer had an argument. He received deferred prosecution and went to counseling. Online court records showed the charge was dismissed. Records also showed he was found guilty of misdemeanor charges of operating a vehicle without a valid driver's license in 2000. He had entered the United States illegally multiple times, according to immigration authorities.

Around a year after Martinez was deported, he was killed by a drug cartel in Mexico, according to his wife.

She went on to raise their children in Manitowoc, where she now works as a supervisor at Wisconsin Aluminum Foundry.

“I just celebrated the graduation of my three girls from high school, and the sad part was they would have loved to have had their dad there. Because of immigration policies, our family was ripped apart, and they will never have their dad at the important events in their life,” Estrada said.

Still, Martinez wouldn’t have wanted his children raised in Mexico, and as painful as it was to let them return to the U.S. without him, he knew it was the right decision, according to Estrada.

“He absolutely knew the whole reason why he came here to begin with, and then having children, he didn’t want them to grow up the way he did,” she said.

Estrada went on to be a co-founder of Crusaders for Justica, an immigrant rights group in Manitowoc.

Biden’s executive action Tuesday was a step in the right direction, she said.

“We’re going to see people come out of the shadows a bit and thrive,” she said. “It’s not a nice thing watching them be scared every single day, worried about their families being torn apart. Having lived through that, I know the feeling. When it happens, it’s like a complete bomb that goes off in your life.”

But she said the new rule doesn't go far enough to protect others.

To be eligible, immigrants must have resided in the United States for 10 years or more as of June 17, 2024, and be legally married to a U.S. citizen by that date. That leaves out many people who would benefit from the rule change.

Under current law, many migrants seeking legal status must first depart the United States and wait to be processed abroad, which can take years, with no certainty of being allowed to return. The new rule will allow undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens to stay in the United States and work for up to three years while they seek permanent legal status. Under the criteria, they cannot have posed a threat to public safety or national security.

The rule could shield about 500,000 undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens from deportation, according to the White House. It also would provide protections for about 50,000 people under age 21 who are the children of a migrant who is married to a U.S. citizen.

New work permit could be 'life changing'

One person who could benefit from the new deportation protections is Megan, a U.S. citizen from the Milwaukee area, whose husband has lived in the U.S. illegally for many years. To protect the couple’s identity, the Journal Sentinel is not publishing Megan’s last name.

Through something as simple as traffic violations, her husband could be deported to Mexico, forcing her to make the difficult decision to leave with him or remain here.

“The current immigration policies have actually hurt U.S. citizens and 6,000 Wisconsinites in the same situation as me,” she said.

Megan said her husband has worked in restaurants and for landscaping companies, but without legal status, it’s been difficult to receive promotions.

“Just having the work permit could be life changing,” she said.

There are undocumented individuals in Wisconsin with medical and engineering degrees doing service industry work, which is honorable but not realizing their full potential, said Christine Neumann-Ortiz, co-founder and executive director of Voces de la Frontera, an immigrant rights group in Milwaukee.

“In Wisconsin, we still don’t have access to a driver’s license for people who don’t have some kind of legal status,” Ortiz said.

She agrees with Estrada that Biden’s executive action, while helpful, doesn’t go far enough.

“It’s definitely not as broad as it could have been, or should be,” Ortiz said.

'We would not be America’s Dairyland without immigrants'

It's also not a substitute for immigration policy reform, which has languished for decades.

While the nation’s elected officials have been deadlocked over the policy, companies like Wisconsin Aluminum Foundry have come to rely on immigrants to fill jobs which otherwise would have been left vacant.

Sachin Shivaram, the company's chief executive officer, has hired people from Latin America and other parts of the world he’s not especially familiar with. Some of his immigrant employees speak English but many do not. To assist them in the workplace and their daily lives, his company offers language classes.

“We celebrate diversity. But we also recognize that our workplace can be dangerous, and our safety depends on being able to speak with each other,” Shivaram said.

Dairy farms have also become heavily dependent on immigrant labor. By some estimates, immigrants comprise around 80% of the hired help on large Wisconsin dairy operations — doing hard, physical work that others no longer want.

“We would not be America’s Dairyland without immigrants,” said Tina Hinchley, a dairy farmer from Cambridge and vice president of Wisconsin Farmers Union.

USA TODAY contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Immigration policy a positive for some Wisconsin, too late for others