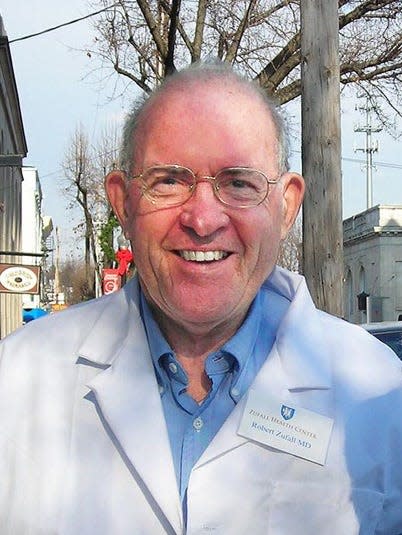

What can we learn from Bob Zufall, NJ’s humanitarian role model?

Dr. Bob Zufall’s retired colleagues couldn’t turn him down in 1990 when he asked for volunteers at the modest, free health clinic he was creating in Dover.

They didn’t know that his one-night-a-week operation would grow into an award-winning, seven-county behemoth that now serves some 45,000 uninsured or under-insured patients who otherwise would swamp hospital emergency rooms. But they knew their old friend and his wife sometimes flew to South America to help treat the impoverished.

How could they say no to New Jersey’s version of Albert Schweitzer?

It might seem like a stretch to compare the self-described country doctor, who died in March at age 99, to the towering humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize winner who — in his thirties — sacrificed nearly all human comforts to treat natives at a clinic in equatorial Africa. At 65, Zufall was a comfortably retired urologist when he began offering free, primary-care treatment to the poor in a church basement a few miles from the Mountain Lakes home where he and his wife, Kay, raised five children.

Unlike Schweitzer, who endured brutal conditions including imprisonment during his early days as a missionary doctor, Zufall’s mission entailed little personal sacrifice. But like Schweitzer, he felt impelled to fill a need that few others fully recognized at the time.

“There’s a lot of poor folks right here,” he recalled telling Kay when she suggested a return to Peru.

Although Morris County consistently ranks among the nation’s 10 wealthiest counties, its poverty level was more than noticeable to physicians who treated immigrants and other non-English-speaking patients in hospitals such as Dover General. Now part of St. Clare’s Medical Center, that’s where Zufall practiced for 36 years, a period that marked a sharp rise in New Jersey’s Hispanic population, especially in Dover where Latinos now account for 70% of the town’s residents.

“How about staying in Dover?” he said, knowing full well that his wife would agree.

The ideal helpmate

Luckily, Kathryn Schwindt Zufall was a no-nonsense organizer who recruited volunteers to help staff the little office, as well as local donors who supplemented the coins and dollar bills that patients dropped into a little box.

“Everyone knew she’d never take no for an answer,” said my wife, Susan, who — full disclosure — was a public relations consultant for the health center for several years.

Watching the little Dover Free Clinic morph into the larger Dover Community Clinic, we couldn’t help but admire the generous, self-effacing doctor who had a kind word for everyone, and the tough, onetime teacher who once convinced a local merchant that sending his used furniture to her pet project would do much more good than leaving it for the garbage hauler.

Kay, who died in 2014, was especially good at cultivating friends in high places — often unbeknownst to her modest husband. As Dr. Bob noted in a 2019 interview, state health department staff surprised him in 1971 with a phone call asking for a tour of his clinic. Soon he was shaking hands with the health commissioner himself.

“This guy, Bruce Siegel, came and I was pretty embarrassed,” he recalled, “I said, ‘This isn’t much of a place. It’s just a little thing,’ and he says, ‘I like it; I’ll give you $100,000 a year!’”

In its news columns, The New York Times placed the figure at $97,500 — enough to pay a full-time nurse, a part-time social worker and some supplies, but not nearly enough to sustain what was becoming a six-day-a-week operation swamped mostly with non-English-speaking immigrants, the unemployed and the working poor.

As Albert Schweitzer knew in the early 20th century, financing a fledgling clinic took much more. A renowned lecturer, theologian and organist, he managed to raise capital by performing at concerts and lecture halls throughout Europe and America. In the late 20th century, the Zufalls lacked that sort of star power.

They didn’t realize it then, but their timing was nevertheless exquisite.

Federal healthcare reforms

Starting in the 1990s, federal legislation began recognizing centers like theirs as important safety-net providers specifically designed for underserved urban and rural communities. Regulations demanded that primary-care patients could not be denied treatment -- even if unable to pay. Once accepted as a Federally Qualified Health Center, a community clinic was eligible for substantial planning grants and operational funding.

“FQHCs are the wave of the future,” Zufall proclaimed. “They do a good job and… they regulate us closely.”

But as the couple moved into their eighties and Kay grew ill, could they continue to manage their brainchild under the heavy bureaucratic requirements that government support would surely bring?

Schweitzer faced similar challenges. His brainchild eventually included 70 buildings and 500 beds, but he never installed phones, running water or modern electricity. He never relinquished control, and after his death at age 90 in 1965, critics called him a racist, which sharply conflicted with his oft-quoted “Reverence for Life” beliefs that all lives deserve respect.

By contrast, the founder of the little Dover operation stepped back gracefully, “so the clinic could be sustained and flourish,” said Eva Turbiner, a veteran healthcare professional and business-development consultant who became the center’s president and chief executive officer.

But Dr. Bob was still on the job — full-time.

Remaining a board member, he embraced Turbiner’s plans for expanding the center’s reach throughout northwestern New Jersey -- to Hackettstown, Flemington, Morristown, Newton, West Orange, Bridgewater and Plainsboro. Besides additional geography, these satellites targeted new categories of need including farm workers, veterans, diabetics, public housing residents and the homeless.'

Obituary: NJ 'visionary' who founded Zufall Health network for low-income patients dies at 99

Cash to reinforce the dream

“He put his money where his mouth was,” Turbiner told a crowd of 160 who attended Dr. Bob’s memorial service in April. “In addition to endowing the clinic at its founding, he put up the down payment for a new headquarters in Dover and he was the first major donor to support construction of our West Orange office.”

In 2009, he and Kay were given the New Jersey version of the prestigious Jefferson humanitarian award for their volunteerism. It wasn’t the only time the center received top honors. Pharmaceutical giants such as Becton Dickinson and foundations such as Direct Relief, which specializes in humanitarian aid, began taking notice of the once-tiny clinic that kept producing innovations for reaching vulnerable people from their strategically located offices and specially equipped mobile vans.

“You win every damn award we think up,” said Direct Relief’s president, Thomas Tighe, at a fundraiser for the center in 2021, “and it’s because Zufall is at the top of the top in terms of all the things that matter.”

Such compliments tended to embarrass the center’s founder. He bristled, for example, at a proposal to rename the center for him and his wife. The board summarily overrode him.

“I was just trying to be humble,” he later told Fran Palm, who succeeded Turbiner last year as the center’s top executive.

‘Rock star’ recognition

Nevertheless, whenever he visited any of his center’s 10 clinical sites, neither humility nor advancing age dampened the adulation that the staff showered on their namesake -- even though many were meeting him for the first time.

“They treated him like a rock star!” said Turbiner. “He was our chief cheerleader.”

Remarkably, as he neared the centennial of his birth this year, Dr. Bob remained active in nearly all health center functions including three-hour board meetings -- often via Zoom -- over policy issues that might induce sleep in a man half his age.

“Here was this 99-year-old studying compliance-risk assessment analyses, reviewing by-laws, sliding fee schedules and financial reports — and loving it!” fellow board member Bill Shuler recalled at the memorial service before pausing o ask the audience: “What are you doing with your spare time?”

Dr. Bob did much more than cheer. He was a gifted role model who used the time he had left to set an example -- a term that a famous Nobel laureate once defined this way: “Example is not the main thing in influencing others; it is the only thing.”

Unlike Albert Schweitzer, Robert Bunger Zufall might not have qualified for the Nobel Peace Prize, but his medical legacy and the way he achieved it surely rival the achievements of the 1952 winner. Others have founded hospitals and made huge financial contributions. Many have volunteered their medical talents or sat on boards of directors. Some have even saved lives and improved the health of tens upon thousands of vulnerable people.

But as Fran Palm noted, few, if any, did all that for more than three decades for no pay AFTER formal retirement at 65 — simply for the privilege of helping others.

“He’s the kind of person I’d like to be in the last years of my life,” she said.

John Cichowski is the retired Road Warrior columnist for northjersey.com. He can be reached at jwcichowski@optonline.net

This article originally appeared on Morristown Daily Record: Bob Zufall was NJ's humanitarian role model