I left Memphis, Tennessee, at 18. Here's why I decided to come back after 35 years

I was born and raised in Memphis but left at age 18 and did not return as a resident until I was 53 years old.

Giving full disclosure, I am writing this from the specific viewpoint of a Black, born-and-raised Memphian, alive from the late 1960s until now. During that specific span of time, there has existed in Memphis a self-loathing, a brutal and relentless compounding of negativity, and a general spiritual heaviness in the Black community that has been passed down to each subsequent generation.

When I graduated Melrose High School in 1985 and moved away from Orange Mound to live on my own for the first time, I had no plans to ever return except to visit. Why would I?

I had been infected by the same vague pall that seemed to have been cast over this town that made many of us unreasonably ready to abandon our lifelong home for life elsewhere. Memphis, for lack of a better descriptor, was just Memphis; a wearily slow, sad, countrified, unmotivated, quicksand-walking populace that did not seem to want much more than it had in any given moment. That said, I happen to love my city. Ultimately, that is why I came home.

Pride in community was wounded by Martin Luther King Jr.'s killing

Orange Mound, an historic neighborhood in Memphis, was built during the 1890s and became the first American neighborhood to be built by and for Black Americans. I mentioned the Mound here to establish from whence my high self esteem originated.

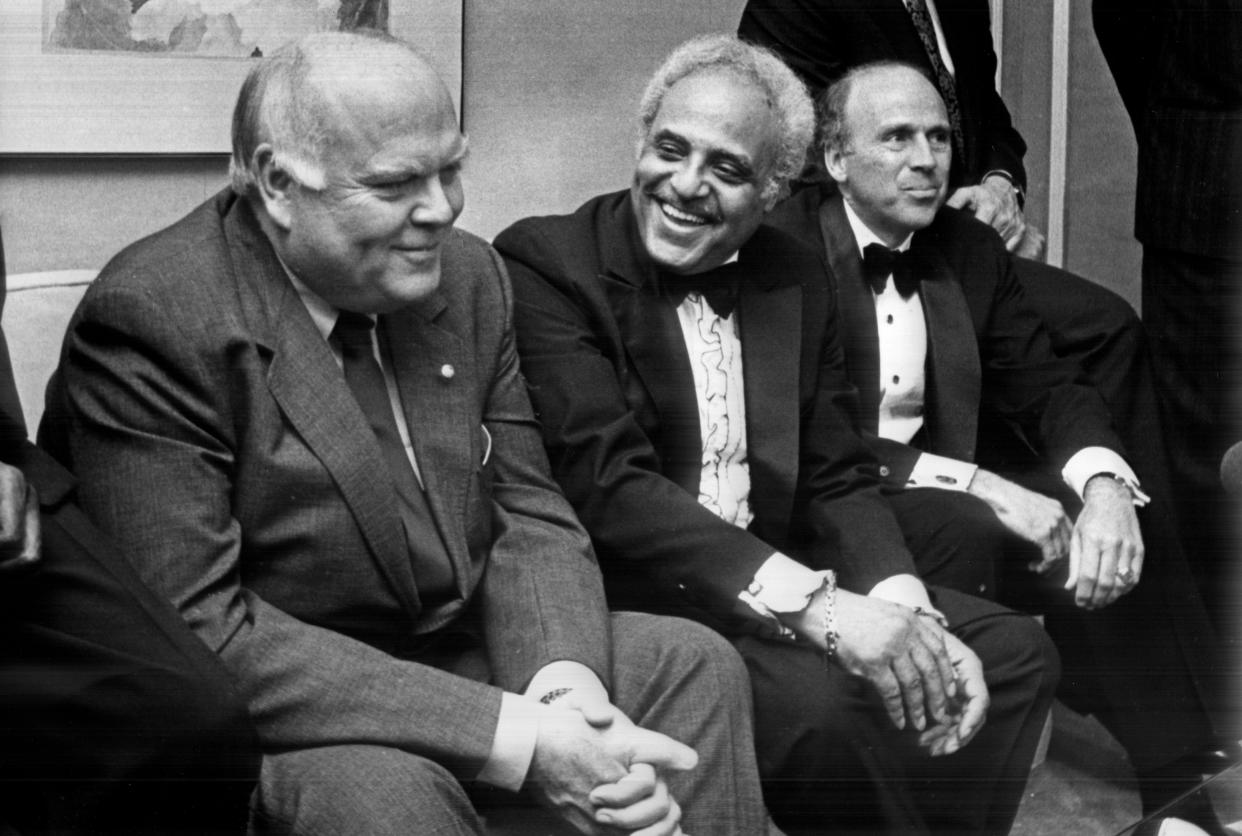

I used to listen to my father, the late Rev. Kenneth T. Whalum, wax poetic about his city. His face would light up reminiscing about the pride Black folk took in the successes of fellow Black Memphians such as Benjamin Hooks, Vasco and Maxine Smith, Russell Sugarmon, W. Herbert Brewster, Dr. Charles Champion, and last, but not least, his very own father, Hugh D. Whalum, founder of what was the Union Protective Life Insurance Company.

Many of them had been “the first Black” this or that in town, and he was proud of what they meant to the Black Memphis community at large.

It is my opinion that in the decades since the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. much of the Black community in Memphis has stagnated and borne the brunt of inordinately low self-esteem due to both inaccurate and incomplete ancestral education blended with a self-imposed curse.

I believe that April day in 1968 was the seminal event and causative seedling of the curse of our societal withdrawal in Black Memphis. Not all, but enough of us seemed to give up on trying because Dr. King died on our watch.

More: Memphis in May started in 1977 to bridge racial differences and rebuild weakened downtown

Pride in the ancestral and communal achievement increases everyone’s self-esteem. My dad was a successful and driven man. As I look back on him now, I like to think he felt a subconscious connection to that intestinal fortitude and hubris necessary to not only survive but succeed.

His African ancestors obviously possessed the same drive, having endured the Middle Passage. Dad believed in himself, and low self-esteem was not a part of his existence. He was not a victim of the curse.

Lessons from Accra, Ghana about our ancestors

I have been blessed to see the world. Extensive travel gives one perspective, and it made me appreciate what it means to be of African descent.

To be sure, television and a myopic, untraveled local environment were the culprits who mistaught me a great many things about Africa I have gratefully unlearned over the decades since leaving Memphis. I now link my father’s, both brothers and my high self-esteem not only to our faith in God, but to our African ancestry.

More: Red Zone Ministries tackles the tough challenges facing Orange Mound's youth | Norment

The greatest experience of my life outside of becoming a father was my visit to an area near Accra, Ghana, called Cape Coast. Cape Coast was one of the African ports of the Atlantic slave trade. In 1482, the Portuguese erected the Elmina Slave Castle there. I visited Elmina, and the following is a report of my experience as we were taken on a tour of that brutal and sobering facility.

As the 97,000-square-foot castle came into view, the car fell silent. It was a gigantic white-washed, weather-eroded stone prison that sat on the ocean’s edge. Calling it a castle bothers me still. Our guide ushered us to the entrance and began the tour. His Ghanaian accent was the only sound other than the waves of the ocean. He led us into the middle of a courtyard as he pointed to one side and explained that was the dungeon for the male Africans. The other side was for females.

Each dungeon housed up to 200 bodies at one time for a total of 400 confused, fearful, and furious human beings who were never going to see Africa or their families again. The guide then pointed behind and above his head to a small balcony which sat above a chapel onto which the prison overseer would daily stand and point out the female he wanted to rape that night. His guards brought her. I repeat, the warden stood atop the chapel…and chose the night’s rape victim. Any woman that fought him was taken to the castle’s edge, murdered, and thrown to the sharks below.

We were led into the male dungeon. I remember the feeling of standing in a stone-carved room with neither simple egress nor consistent airflow after an unfathomably thick and heavy wooden door had been shut behind us. This was the same space where legions of my ancestors stood, sat, slept, ate, drank, defecated, urinated, vomited, wailed, and died over the 90-day breaking period. Only the strongest of the strong made it to the 91st day. There was a single hatch about 30 feet above their heads from where food and water were dropped. I cannot imagine the intolerable stench of human decay. Try to remember the hottest temperature you have ever endured but imagine it in a stone dungeon with 199 other men or women.

The inhumane treatment of our ancestors is not to be mistaught or forgotten. After the 90-day breaking period, the remaining Africans were led down a corridor to the door of no return. The door was made narrow so they would have to walk through single file. The first step outside of that prison in 90 days was into the hull of a slave ship. My emotion after this tour was a flow of silent tears mixed with a newfound understanding of Black pride. It hit me hard. When you stand where they stood hundreds of years earlier and you listen to what the tour guide is teaching, your imagination makes you hear their screams. Your olfactory sense conjures the smell of sweat and decomposition. Suffice it to say those who survived the brutal voyage and disembarked in the Americas were considered the strongest of the strongest. That was my father’s link. That was his connection to his heritage; his unyielding strength and mettle.

A young Black male or female visiting Elmina leaves transformed. Hosea 4:6 reads, “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.” That verse encapsulates the plight of Black Memphis. When we have accurate education of the strength of the ancestors before us, we feel, think, and do better. When systems collude to deceive us about the accuracy of our history as we see happening in the educational system in Florida, and we allow it to happen, generational ignorance is the outcome.

High self-esteem in Black Memphis must stem from positive reinforcement, accurate representation, substantive teaching, and environmental examples that do not seek to elevate our race above others, but rather to instruct a Black person on the high value of his ancestry and ability. Those ancestors have bequeathed a strength that is unsurpassed in human history. Too few of us know that.

How to solve the Black Memphis crisis

Therefore, here is what I propose as a solution to our current problems as it concerns Black Memphis. I believe it can repair the damage done to our collective consciousness in America in general.

Memphis needs both companies and wealthy, forward-thinking individuals who are willing to invest in her future viability and health to purchase quarterly flights to Accra, Ghana, for the sole purpose of taking this tour and teaching our youth accurately as descendants of some of the strongest humans the planet has ever known.

I do not believe a person returning from this experience would be eager to injure another Black person. This would be a massive financial undertaking, but the return on societal investment over time would be incalculable, legendary and repeatable. It would also etch the names of the private citizens and companies who fund it into a place in history of which few can boast. If our government can spend billions of dollars on war aid, can we as citizens not do at least as a fraction as much to ensure a vibrant, safer, more accurately educated America?

Drastic times call for drastic measures. And what better place than Memphis, Tennessee?

Memphis native Kevin Whalum is a vocalist, minister and motivational speaker. For decades, he lived elsewhere, including Nashville, until he returned to Memphis in 2020.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Black Memphis perishes for lack of knowledge and worldly experience