The Etiquette of Dissent

On the night of November 5, somewhere between 40 and 50 percent of you will begin a period in which your preferred president is out of a job. If you’re in that club, congratulations: It eventually includes everyone.

The etiquette of living in dissent thereafter, especially if it goes on for a long time, is another matter. In theory, we are supposed to learn how to be good losers as kids. Athletic leagues give out sportsmanship awards, and institutions like the Scouts try to coach their members toward grace in defeat. Both aim to teach us how to live on the outs, perhaps drawing upon the British public school attitude of let’s-all-pull-together-for-the-empire. (The out-of-power party in the UK is even known as “His Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition.”) In the American ideal, we metaphorically line up and shake hands after the softball game, and then square off again on another day. In practice, what some people do is accuse the other team of cheating and try to get the umpire fired.

If there’s one place where dissent is particularly baked in, it’s the Supreme Court of the United States. As part of every opinion that’s not unanimous, one of the justices who disagrees with the decision writes a counterargument, and it traditionally ends, “I respectfully dissent.” The nine judges argue it out behind closed doors, they write their arguments and counterarguments, the whole business gets published, and (as in the softball game above) it’s on to the next case. Although in recent years the wall of silent civility that they once presented has begun to rattle a bit, we do not have justices on the dissenting side saying they simply refuse to accept a decision.

That’s because they know that dissent itself is the defining quality of American history. At the very creation of America, the presidential historian Alexis Coe has noted, George Washington had become accustomed to deference from his military advisors, and once in office he discovered that his political deputies were much mouthier. “Washington invented the cabinet,” she says, “in order to recreate the council of war, and assumed that its members would leave the fight at the president’s house. They did not! It spilled onto the streets, and that gave birth to partisanship.”

Which is not to say that the founding fathers discouraged dissent. Ralph Young, a Temple University history professor and the author of Dissent: A History, points out that they brought it up in the very first sentence of the Bill of Rights (“Peaceably to assemble” and “petition the Government for redress of grievances”—there you go). “Americans haven’t shut up since,” Young says.

Juliet Hooker, a political science professor at Brown, brought up another point when I asked her about the easy charge that loving your country somewhat conditionally is un-American. “Not criticizing your country when it’s wrong is not a correct account of patriotism. It’s basically saying you should blindly follow what your group does, and that has historically led to some really horrible outcomes.” Arguably, the sorest losers of all time were the apologists for the Confederate States of America, whose Lost Cause myth allowed them to justify a century and a half of dehumanizing oppression.

In fact, Hooker, in her book Black Grief/White Grievance, argues that Black Americans have been coaxed to lose extra well, even when faced with systematic injustices. Any deviation from purely nonviolent protest has usually been condemned from left and right alike. As Martin Luther King Jr. once put it, his white supporters often demanded that reforms come “at bargain rates”—that is, incrementally—and even then, activists would face a backlash, or at least the fear of one.

There are politicians who would rather be right than in charge. Certain stubborn characters like Ron Paul and Bernie Sanders have historically been so unwilling to compromise that they never got much traction, legislatively speaking, toward their biggest policy goals. Others who were more willing to play ball sometimes just came along at the wrong time. Adlai Stevenson, a brilliant Democrat who had the bad timing to run against the hugely popular war hero Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, spoke graciously when he got clobbered. “It is traditionally American to fight hard before an election,” he said, adding, “It is equally traditional to close ranks as soon as the people have spoken… We vote as many and we pray as one,” and calling for dignity.

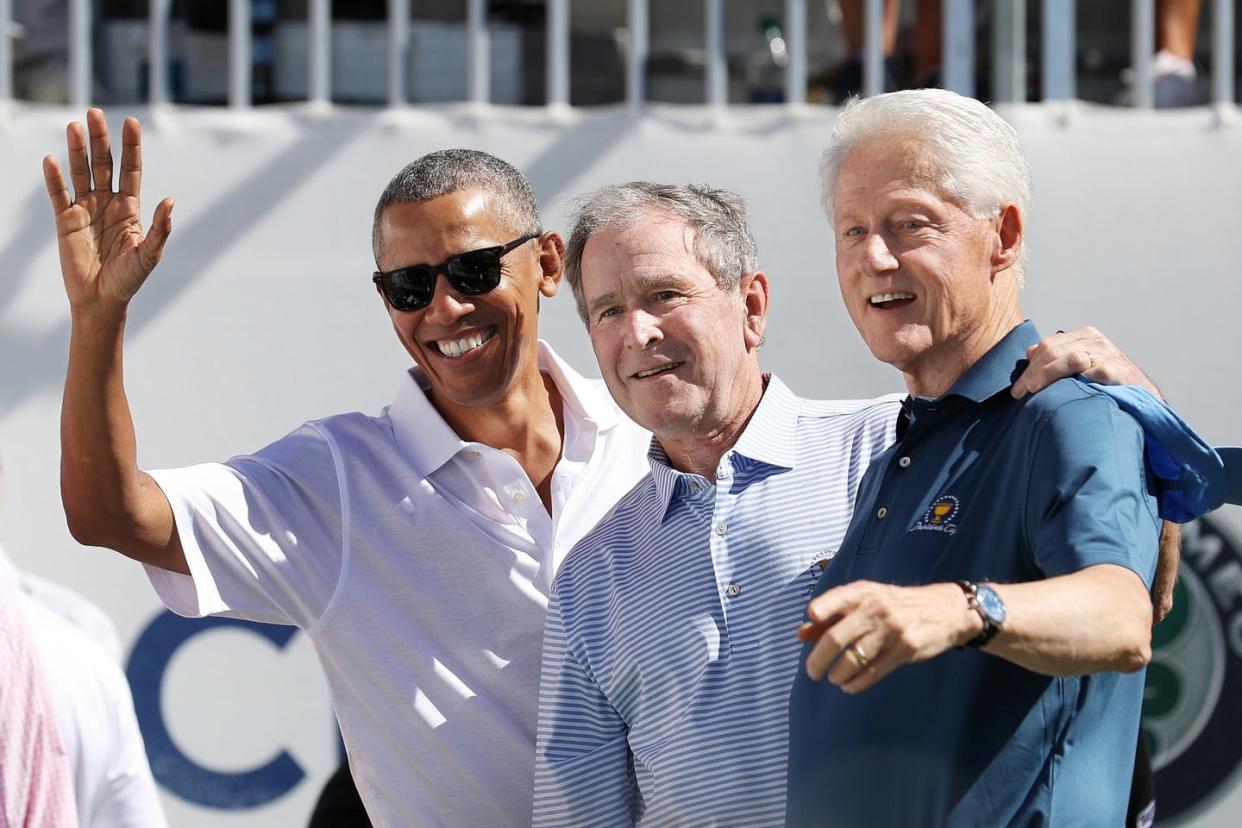

Nearer to our own time, the standard for grace in defeat was perhaps set by the letter that George H.W. Bush left in the Oval Office for Bill Clinton, who had just drummed him out after one term: “When I walked into this office just now I felt the same sense of wonder and respect that I felt four years ago. I know you will feel that too… Your success now is our country’s success. I am rooting hard for you.”

Enlist Your Opponents

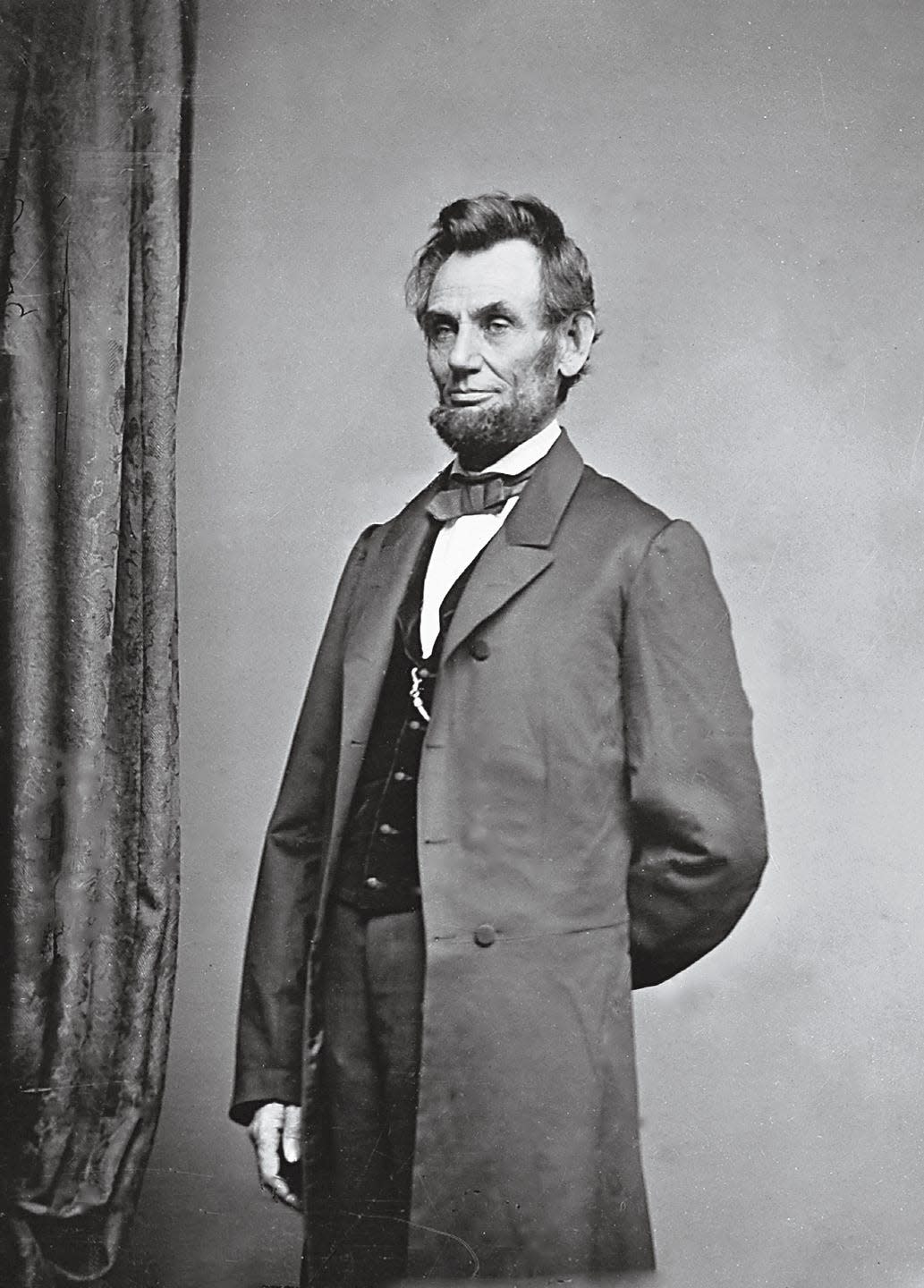

In fact, Bush and Clinton, having joined the tiny club of people with whom the buck ultimately stops, grew to be friends and confidants. Most famously of all, Abraham Lincoln brought his political enemies into his administration, the legendary “team of rivals” for which the historian Doris Kearns Goodwin named her best-selling book. “Lincoln,” she wrote, “understood the importance, as one delegate put it, of integrating ‘all the elements of the Republican Party—including the impracticable, the Pharisees, the better-than-thou declaimers, the long-haired men and the short-haired women.’ ”

Yet it gets tiresome even for the best of presidents. One of George Washington’s reasons for stepping away from the presidency after two terms was that he was sick of all the criticism. “Thomas Jefferson said he’d never seen anyone so sensitive to criticism,” Coe says. Same for the seemingly bulletproof Lyndon Johnson. When he quit his run for reelection in 1968, Coe says, “part of the reason was the prospect of facing protesters at every campaign stop.”

Persist, But Be Flexible

Pridefulness may be the most common source of bad etiquette after a loss, as it can metastasize into a prolonged petulance or much worse. On the other hand, a strong emotional constitution allows one to shake it off and move on to the next thing. Jimmy Carter, a mild-seeming character with much more political cunning than people give him credit for, got routed in 1980, after one semi-effectual term in the White House; he spent the next four decades living his principles. In losing the presidency he won something larger: a platform on which to do good outside of politics.

Which brings up a key aspect to keeping your sanity in dissent: forging on. At some point you’re likely to want to get something done rather than just stewing. For that you will have to find points of agreement, or at least shared goals, with powerful people you disagree with. Sometimes it even means accepting that the other side might have a point. Ralph Young reminded me that when Franklin Roosevelt demolished the Republican opposition in the 1932 election—and over the next six years built up immense majorities in the House and Senate—quite a few Republicans basically went along with his New Deal legislation, sensing that the nation had not only spoken but shouted.

Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Antonin Scalia were very much ideological opposites on the Supreme Court. Neither of them was one to shrink from a good argument. In the 5–4 Bush v. Gore decision that chose a president, Ginsberg’s minority opinion declined the customary politesse in its language when she left out one word. “I respectfully dissent” became “I dissent.” In several subsequent decisions in which Scalia wrote in the minority, he did the same. Yet the two, away from the court, were genuinely close, bonded by a shared love of, among other things, opera. At Scalia’s memorial service, she referred warmly to the value of his “jeering” notes on her drafts and recalled his explanation of their friendship: “I don’t attack people—I attack ideas. And some very good people have some very bad ideas.” Even if you believe that Scalia’s preferred ideas were the bad ones, you’re tacitly agreeing with him on this one point, and maybe you’re on your way to finding a tiny bit of common ground with the enemy. Welcome to the politics of 2025.

This story appears in the October 2024 issue of Town & Country SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like