The Rise and Fall of a Gay Porn Empire

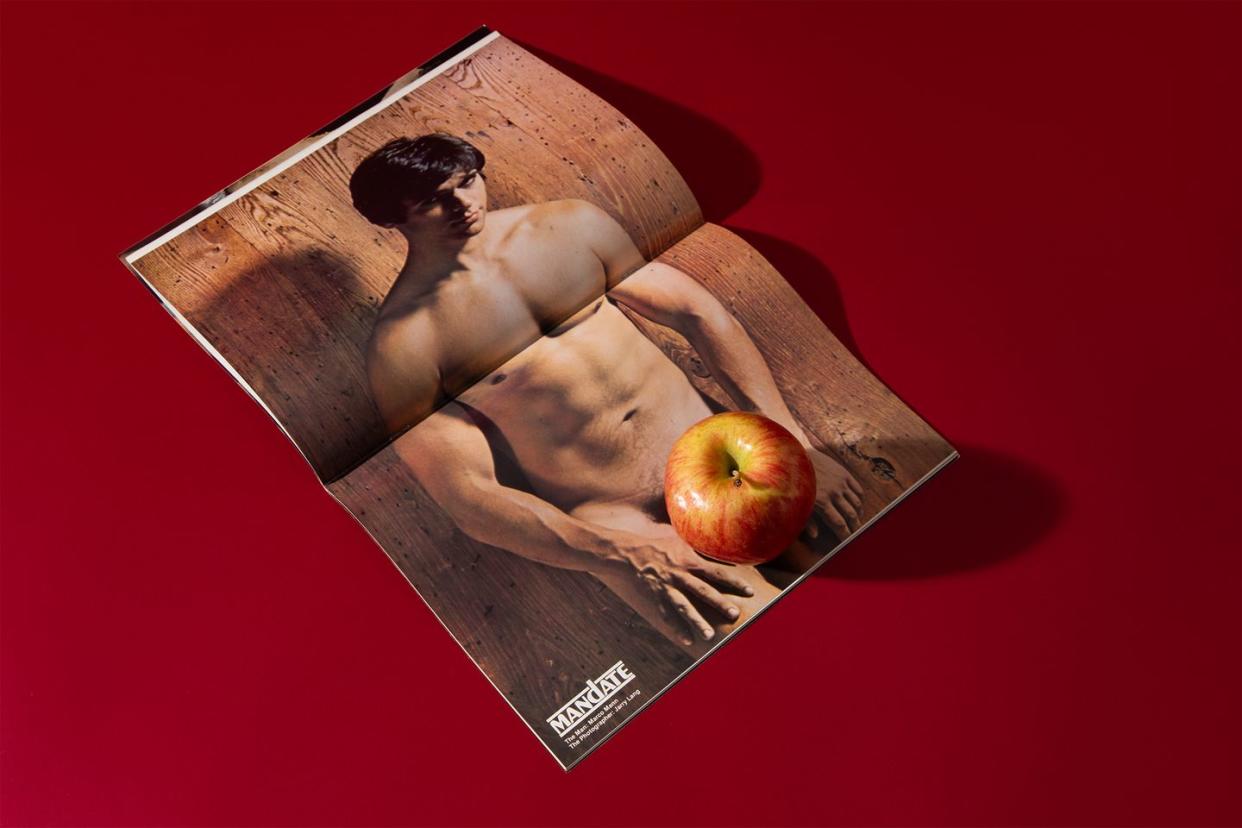

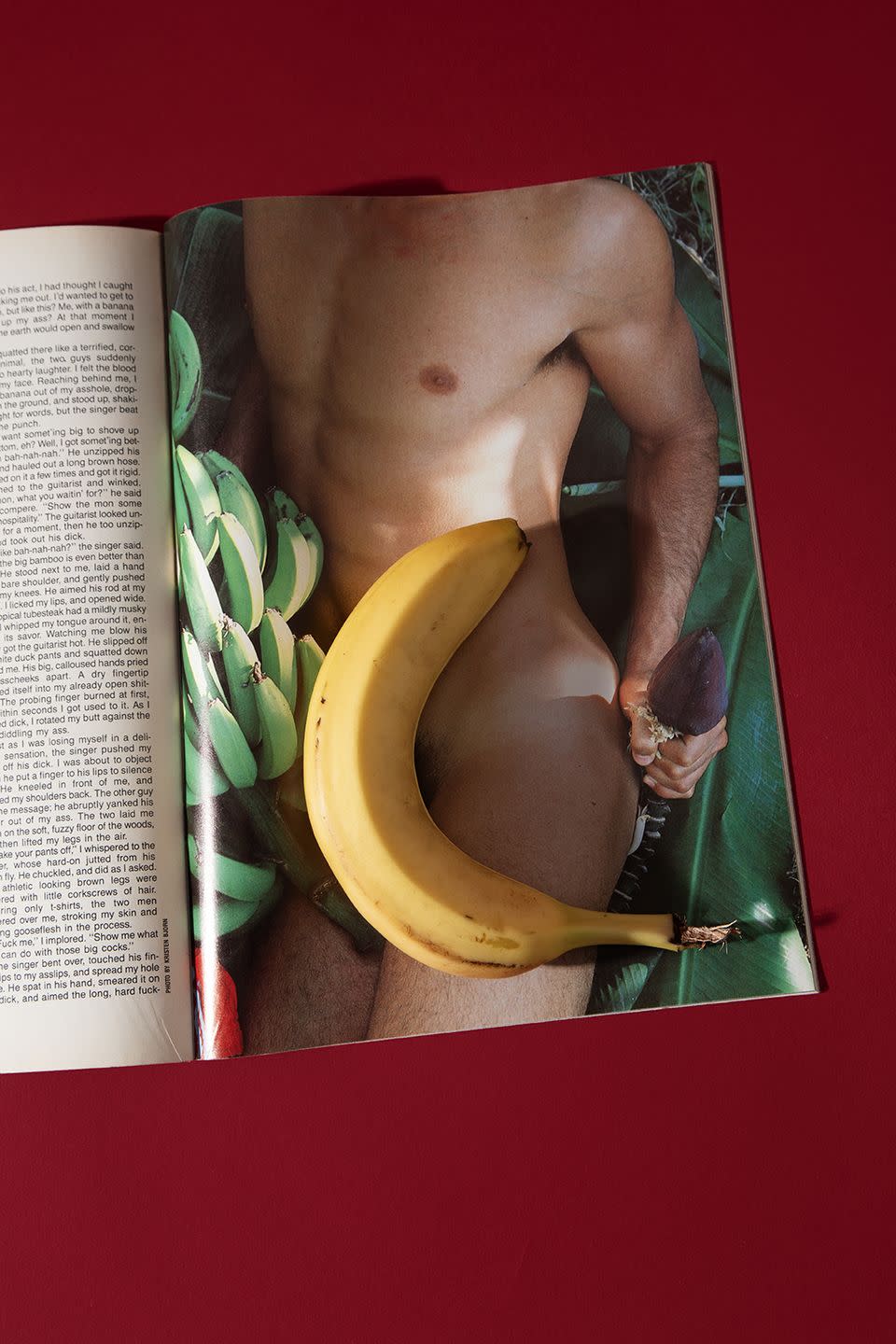

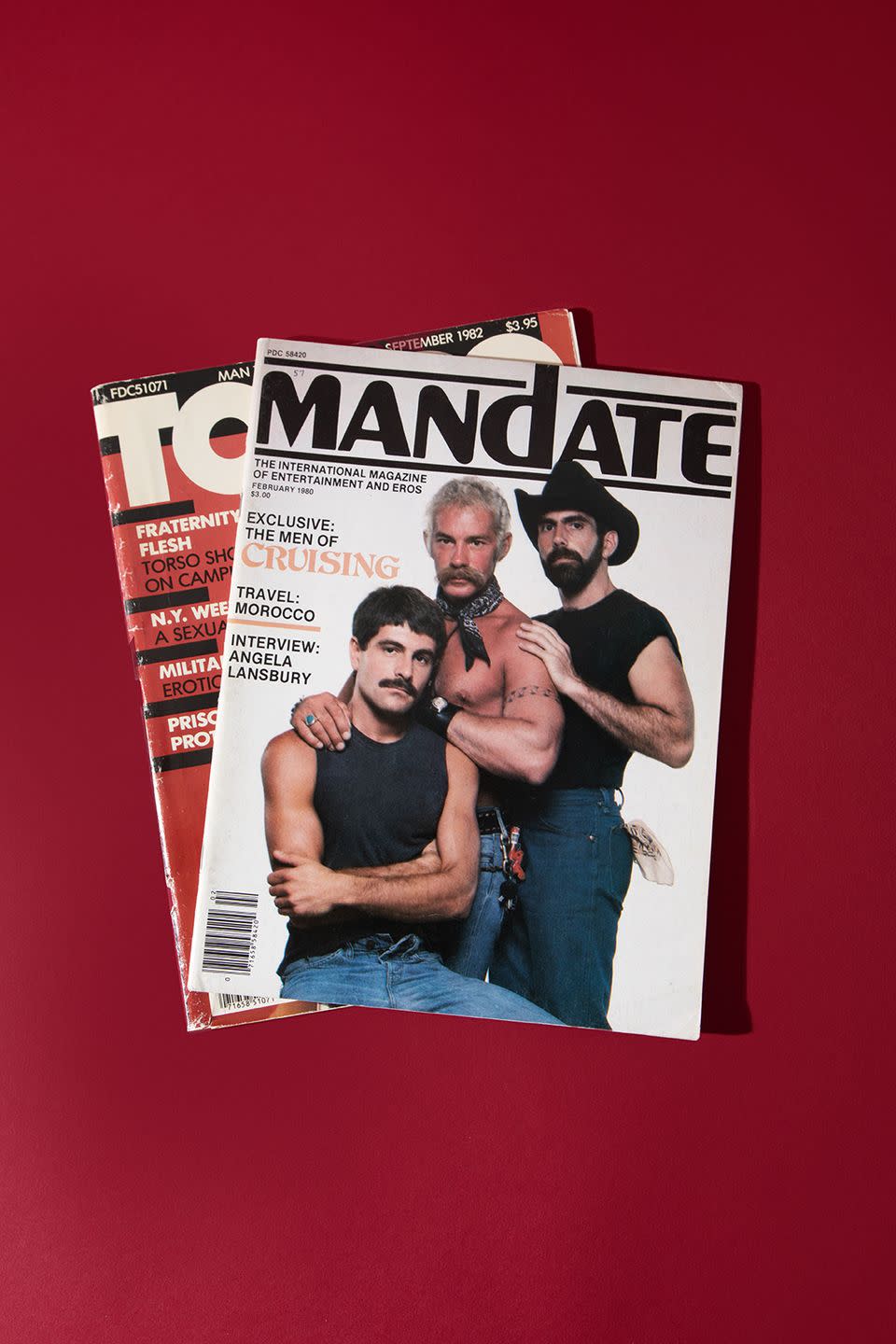

At America’s premier gay-porn publisher, dick size was king. Every model we published had to be attractive and fit, but it was their equipment that determined where they would end up. If a guy was going to be an Inches cover man, his member had to be jaw-dropping. Playguy called for boyish bulges. To appear in Mandate, the flagship, his dick should be attached to a body and face almost no reader would turn down.

And if a guy was going to show off his cock in Torso, where I worked, it had better be positioned below a six-pack.

These publications were housed in unassuming offices in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood. But the company—variously called Modernismo, Mavety Media Group, and MMG Services during its reign—was run by a larger-than-life personality: George Mavety, a straight man with a huge appetite for both sex and food who looked like a 1920s fat-cat caricature by the time I arrived in the mid-nineties.

Joining Torso wasn’t the obvious next step in my career—I’d worked for a literary agent, a book publisher, and Reuters. I quickly got over my worries about working in porn, but Mr. Mavety, like all men in three-piece suits, terrified me, even if my pedigree as a published novelist endeared me to him. He craved respectability, and loved to present himself as a pillar of his suburban New Jersey community.

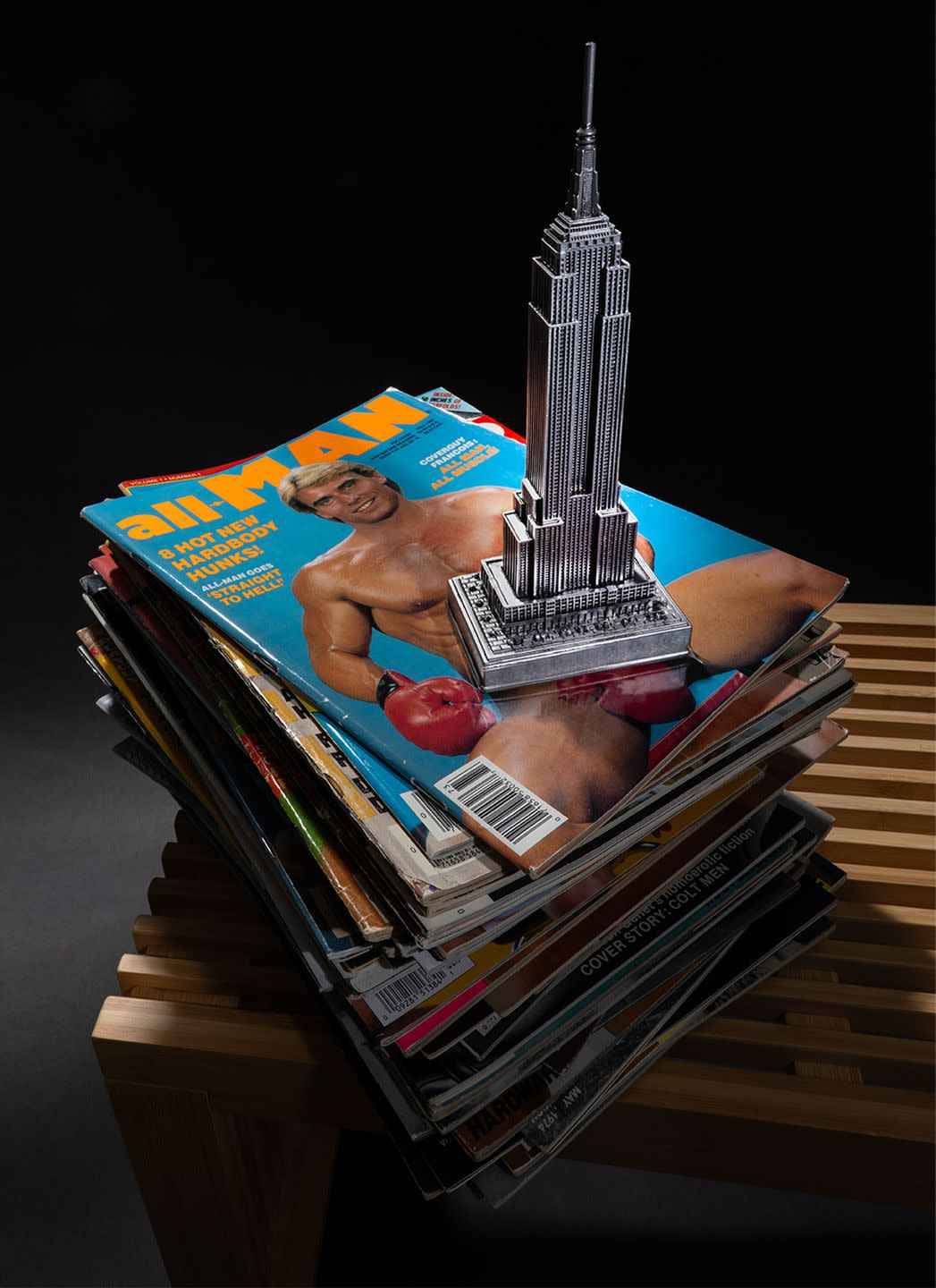

The business was two decades old at the time and thriving. Pre-Internet, the market for gay-porn magazines was highly lucrative. Along with a hundred magazine titles and a handful of mistresses, Mavety amassed a fortune of up to $36 million during the twenty-six years he ran the company.

Magazines had been in people’s lives for more than a hundred years. And as long as God made little boys, a percentage would grow up wanting to see man-on-man action. What could go wrong?

The pay sucked, but every day was an Andy Warhol short film.

It was also gay history, and a lifeline to gay men across the country. Mavety’s magazines—which were published from 1975 to 2012—were tastemakers, sexual and otherwise, representing the intersection of pornography, publishing, and gay rights. They played a role in the radical changes that occurred across all of these areas in the past five decades.

Over more than eighteen months, I reached out to dozens of staff, contributors, and models from the golden age of Mavety Media. What emerged was a record of a time that swung between historic and hilarious under the watchful eye of Mavety, whose outrageous eccentricities and many moods kept us on our toes. Here is that history, in the words of the people who lived it.

Prior to the late sixties, selling images of nude men was illegal. Stonewall kicked off the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement in 1969, but it was a series of court cases that liberated publishers, allowing for the exploitation of the male form. The decisions were victories for capitalism but also helped normalize homosexuality.

Freeman Gunter (advertising, editorial; Mandate, Playguy, Honcho editor in chief, 1975–86): The gay market was being recognized as a viable force financially, and someone you might want to appeal to, whatever your personal views about homos.

__ Demand outpaced disdain, and in 1974, George Mavety, a distributor, worked with an editor named John Devere on an ambitious publication called Dilettante, which hoped to be a gay Playboy.

Devere—a flamboyant aesthete who had edited the N. Y. C. nightlife handout “Where It’s At”—set up shop on Tenth Street in the Village, next to the legendary gay bars Julius’ and Ninth Circle.

Perry Brass (writer, 1970s): John Devere was like if Mel Brooks had to do a character of the queeny gay editor. He used to wear jodhpurs.

__ Devere’s assistant was his boyfriend, Joe Arsenault.

Michael Llewellyn (associate editor, 1975–80): It was a classic gay love story: John was teaching Proust, and Joe was in his class. Joe was a bit of an airhead, handsome, good at his job, although he left all the layouts for an issue on the subway one time.

__ With soft sales on four issues, Dilettante floundered. Devere swimming in debt cleared the way for Mavety to propose a replacement title called Mandate, one Devere would be invited to edit—as an employee.

John Cox (photographer, 1974–91): George let John stew, then came back and said, “Let’s bring it back, but this time do it my way—with [more] male nudes.” He was distributing Colt and realized this was the next step in the evolution of gay magazines.

__ Mandate’s premiere issue was April 1975. It was groundbreaking, a gay-targeted magazine with nudity that was nationally distributed—and not just in places where porn like Blueboy was found, but alongside mainstream titles.

Jim Eigo (Playguy editor, 2000–07): Mavety was the first person who could show a boner in magazines that were on the newsstand, God bless him.

Don Hanover (photographer, 1970s): They didn’t do erections, but if something wasn’t pointed up, you could get it in. You could have a fluffed cock sideways.

Karen Mason (owner, Circus of Books porn bookstores, 1982–2019): We had fixtures, and Mandate—those sold hundreds of copies. We would get six hundred copies and we sold almost all of them.

__ Dubbed “Entertainment & Eros for Renaissance Men,” Mandate leaned into hairy guys and porn actors, featuring on its first cover a Jim French photo of model Bill Cable, aka Stoner, who was in a relationship with Cassandra Peterson. She would become known as “Elvira” six years later.

Cassandra Peterson: Bill’s main job was working for a tree-trimming company with his friend Christian Brando.... He modeled for lots of magazines and catalogs, such as the West Hollywood clothing store Ah Men, Playboy, Oui, Colt, Drummer, and, most importantly, graced the cover of the biggest-selling issue of Playgirl. He loved modeling, being the center of attention, and flirting with gay men, even though he was straight.

__ Mandate’s photo credit hyped Cable’s “bold masculinity of the man’s man.”

Inside, readers were treated to the actors of Broadway’s gay play Tubstrip (including porn god Casey Donovan), a review of Equus, a Dog Day Afternoon feature, cabaret listings, and advice on becoming a “sensuous homosexual.”

All that and twenty naked men for just $1!

Charles Moniz (photographer, 1975–’80s): They were trying to sneak their way in.... “Okay, who’s a big fan of Broadway and the opera? Let’s appeal to their crotch, then let them think they’re following their mind.”

__ By the time of its first color cover, in August 1976, Mandate felt more like a smart skin mag than a clone of the closety entertainment title After Dark. It turned gay men on and allowed them to feel seen—literally.

Stan Leventhal (writer; Mandate, Torso, Honcho, Inches, Playguy editor in chief, 1980s–94): You could not find an Advocate... in many small towns, but you could find a Mandate... and these magazines were the first connection that many young men had to the gay community. (Quote from Out Write '90 National Lesbian and Gay Writers Conference)

Kent Neffendorf (illustrator, 1984–2009): It was awe-inspiring to enter a bookstore and see photos of men with bulges and hard-ons. Nothing existed but me and those photos.

Michael Bronski (LGBT historian): These magazines were the basis for a visible gay male culture across the country. People in states where you couldn’t even safely come out in the seventies could find them, or subscribe, and they set a cultural bar: “This is what it means to be gay”... to know who Cleo Laine was, to read the new novel by Andrew Holleran, to know that Fire Island and Provincetown are gay resorts you probably want to go to, knowing who else might be gay—a coded language that’s written, verbal, and visual.

Steve Perkins (production artist, 1977–80): I was kind of aware what we were doing was groundbreaking, but it was also kind of the next step, the next step, the next step, one day at a time.

__ George Mavety’s bet paid off, a win made sweeter due to his hands-on approach to distribution. Stories of Mavety launching Mandate became a staple of his personal mythmaking, delivered in self-aggrandizing oration. People didn’t know where the truth started... or if.

Phil Mavety (brother of George Mavety): In New York, George actually delivered them from the trunk of his car.

Gay pornography and the Mafia have a long shared history, driven not by mutual admiration but supply and demand. Whether or how mobbed up George Mavety was remains a mystery, one he cultivated.

Tom Cicero (art director, late 1980s–2001): My first New York job was at Michael’s Thing, [a] gay [magazine]. Every Thursday, we’d hit the bars and deliver the magazines, collect fees. We’d go to Townhouse and Ramrod and hang out, maybe have a beer, not realizing so many of these were Mafia-owned.

Steve Perkins: My boss, a friend of George’s, wanted me to drive to New York in a van with a bunch of books and sell them on Forty-second to the stores. One day, the guy says, “Hey, heads up—the street’s really hot today.” I was like, “What?” He says, “The Mafia’s on the street—you just better get the fuck out of here.”

Jack Fritscher (LGBT historian): When you think about the Stonewall being owned by the mob.... People presumed Mavety was a made man. Anyone from New Jersey was suspect, especially when you weighed three hundred pounds and smoked cigars.

John Cox: He was Mafia. He gave me some stuff and said, “I want you to put this in my car.” I took it and went down and opened the car, and it was like opening the vault of a bank—fully armored.

Freeman Gunter: He was a gangster! A crook! Completely disreputable. He was outrageous.

Mobster or poseur, the real George Mavety, born in Canada, was complex, described by his surviving older brother, Phil, as one who “never thought small.”

Phil Mavety: Because of the Thousand Islands, there was a lot of fishing going on. He was sixteen and would buy worms, repackage them at the tourist areas on the Canadian side and the American side on a Saturday, and make $300 to $400 a day when people were working for $20 a week.

__ Mavety taught school for about three years on Wolfe Island, between Kingston and the U. S. border.

Phil Mavety: He didn’t really have a teacher degree, as such.

Matthew Licht (Juggs editor, 1996–2001): I heard he was looking at the girl students the wrong way, so he thought he better resign, which I thought was pretty honorable.

__ Born to move merch, Mavety became a car salesman. But the self-determination offered by publishing soon attracted his entrepreneurial spirit and became a lifelong passion. “George was in love with publishing,” says Jack Fritscher, a mainstay of West Coast gay media. He launched a mail-order business, House of Books, in Canada, using the post office as his HQ, and ran a sketchy business in Toronto that was “closed down because of the laws there,” George’s brother says. He moved to N. Y. C. after a time in California.

Dian Hanson (Juggs and Leg Show editor, 1985–2001): He was connected with what we called the California slicks—magazines that were more explicit and sold in tobacco shops and strip clubs. My understanding was he was bankrolled by [the Gambino crime family–connected “Walt Disney of porn”] Reuben Sturman. George... managed to negotiate his way out.

__ Mavety resembled forties movie villain Sydney Greenstreet, an obese man in impeccable suits, always well-groomed and exuding refinement, even if he was also unselfconsciously venal.

Erik Schubert (art director, 1995–2000): He’s talking about cocks and balls and assholes, but it’s “Mr. Schubert,” this super-formal way that he used to talk to everybody.

Sam Staggs (Mandate, Playguy, and Honcho editor in chief, 1982–86): When a company moved in above us, some of their manufacturing process involved ammonia. Unbearable fumes began pouring into my office. I complained and George spoke to them. “Now, you will understand our veddy, veddy severe problem.” They gave him lip, and that’s when he switched back to New Jersey: “If ya don’t remedy the problem, I’ll sue yas!”

Don Hanover: George needed a headshot and had me come to his office to take it. I tried to get a smile and realized “cheese” wasn’t working, so I said, “Say ‘money!’” Which worked.

Scott Harrah (editor, Torso and Mandate, 1999–2004): George Mavety would go around talking to people and say, “Oh, I just bought a $35,000 painting!” and people would be thinking, “None of us even makes thirty-five grand a year.”

__ Ironically, Mavety’s inner struggle was to feel tortured by his size even as the imagery he pumped into the world was of lithe bodies.

Steve Perkins: My memory of him is sitting like Jabba the Hutt behind his desk, puffing cigarettes.

Dian Hanson: My first assignment, he asked me to research penis-enlargement techniques. We didn’t have an Internet, so I was looking in the phone book, calling doctors. What I found is for every thirty pounds a man is overweight, he loses a physical inch of penis. I told him the best way to safely enlarge his penis was to lose weight, so he went on a diet. He would come up and whisper, “Miss Hanson... I’ve gained another half inch!”

Gordon Wallace (Inches editor; Mandate, Torso, Honcho, Inches, and Playguy editor in chief, 1993–2011): I thought him impressively fat, but I was told that a few years earlier he had been Orson-Welles-on-two-canes fat.

Dian Hanson: He was an eating voyeur. He took [porn star] Vanessa del Rio and I out to dinner once and insisted that we order giant lobsters and sat there watching us intently while we ate, encouraging us to eat more, staring with those blue eyes all round.

__ One thing Mavety did not look like was a porn king, albeit one whose gay titles were doing double duty as identity-affirming community builders. Considering that he was married to women and indiscreetly maintained multiple mistresses, his position in gay history is curious. It is possible Mavety viewed “gay” as another kink—and kinks, he understood.

Dian Hanson: He was buddies with Lenny Burtman, who made fetish, female-dominant, cross-dresser magazines. George actually first did some cross-dressing magazines because George was a cross-dresser. I was told by people who had been in his apartment that he had a full wardrobe of female clothes, all in his massive size, and he in fact told me one time in a particularly ebullient mood that he had a custom-made mink coat in his size.

__ Though he was born in rural Canada in the thirties, Mavety never betrayed squeamishness about his rise as a gay-porn titan. “Mandate was gay, but nobody really paid attention to that,” his brother Phil says, “as long as you were makin’ money.”

Mavety kept his work away from his extended relations, but in other ways, it was a family affair. In N. Y. C., he met his third wife—the only wife any of his employees ever knew—Trudy, a German immigrant. They stayed married until his death.

Perry Brass: George and Trudy were utterly, wonderfully tacky.

John Cox: His wife Trudy was the receptionist! She made the curtains for Devere’s office. She and I would sit in that office and bad-mouth George out loud like I can’t tell ya.

Freeman Gunter: His wife told me she would come into his study at night and he would have fallen asleep at his desk with his dick out and the porn magazines spread out—he would look at his own porn magazines and jerk off. Once, he came into the office and threw the new issue down and said, “I couldn’t get a hard-on!”

With Mandate’s success and status as a necessary item for any good gay household, other Mavety gay titles followed: Playguy(1976), Honcho (1978), Stallion (1982), Inches (1985), All-Man(1987), and more.

Andrew Bass (designer, art director, 1989–95): Each of the magazines had their own aesthetic. Mandate was the Esquire—the content was things that were cerebral, literary stuff, lifestyle. Modelesque, clean-cut kinda guys. Playguy was more of the young buck. Honcho was the bears. All-Man was sort of the gym god. Torso was the upper body.

__ Torso (1982), one of Mavety’s main titles, was initially published by Blueboy’s Donald Embinder in California. Though at first seen as a rival to Mavety’s mags, it was actually co-owned by him, moving to N. Y. C. following a tragedy.

Leigh Rutledge (writer, contributing editor, 1981–86): Don had enough contacts in the gay community he was able to get Al Parker for the cover of the premiere issue of Torso. The whole look of the magazine was splashy and colorful, this rich sea-blue background, a bold yellow masthead—attention grabbing. It competed with Mandate.... Its first editor, Jeff Meisner, was killed two years in. I got a phone call very early in the morning and it was Don in tears. He and Jeff were lovers. It was a snowmobile accident. Jeff lost control and crashed into a tree and died instantly. After his death, Don didn’t pay attention to Torso.

Steve Perkins: There was so much material. That’s when Playguy came into being. There was room for a third and it didn’t have a name, so there was a competition. It was my suggestion to call it Honcho. What did I get for that? A pat on the shoulder.

Jack Pretzer (Playguy editor, 1996–2000): In Playguy, it was always somebody’s eighteenth birthday. They were always at their elderly neighbor’s house, watching him remove his dentures to get a blowjob, or getting gangbanged under a swinging bare lightbulb in somebody’s basement somewhere. I was twenty-one—how did I know to write that?!

Jim Eigo: My idea for Playguy was: Tiger Beat with a boner.

__ Mavety even published a bona fide teenybopper magazine, my creation Popstar!, from 1998 until it was sold to Robert Earl of Planet Hollywood in 2000. Secretly publishing it from a porn den was a challenge. The worst that ever happened was when a little girl went to her mailbox, excited to receive her monthly supply of *NSYNC posters, only to pull out a crisp copy of Black Tail, thanks to a mix-up in subscriptions.

Mavety Media was porn, so it attracted outcasts and the sexually liberated. It was also a job, which meant it attracted nine-to-five cubicle dwellers.

Tom Cicero: We’re talking about women in the church choir, some evangelical. I asked them how they squared it with working there. “I don’t worry about what you guys are doing in the back room.”

Cheewai Yip (Honcho designer, 1990–99): There was this guy who worked in subscriptions. If you ever take the elevator with him going up and there’s no other passengers, you do not want to take that ride. One time, he said, “I’ve got a snake in my pants and it wants to spit.... My ass is still bleeding from last night.” He would hit on every man on the street. We would see him in SoHo with some guy wanting to fight him. He’d say, “I just said something nice to this handsome man and he didn’t like it.” I learned how to read people from working with him. He was a king—hysterical, funny, hurtful at times.

Dian Hanson: I remember one day the people in sales were cashing their paychecks. They went out, got drunk, and went to a bank. One of the female members of the subscriptions team started aggressively flirting with some woman in the bank to the point where the bank called George to say they were about to call the police.... The bank people had retreated to some safe room.

__ Then there was George Mavety’s executive secretary, Anne Sheldon. Slight and determinedly dignified, she was kind to everyone and seemed exhausted by her hot/cold business relationship with her boss.

Dian Hanson: George confessed he was a psychological sadist. He would be telling me some of his stories and get this fiendish look and say, “I’m gonna call in Miss Anne!” and he’d call in his puckered secretary and he’d yell at her about something, and she’d get all upset and walk out and he’d laugh—“Ho! Ho! Ho! I can’t resist!”

Scott Harrah: Shortly before Mavety died, Anne had been there thirty years, and he presented her with a gold watch. She was in tears.

Don Hailer (designer, art director, 1996–2009): Anne had been the secretary of Abe Burrows, who wrote Guys and Dolls and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He wrote an autobiography and [thanked] Anne [in it]! I didn’t understand why she was working in a porn office. I felt like we were all there for a reason, and it didn’t matter what that reason was.

__ One woman served as a foil to much of the gay staff, a fussbudget we’ll call Ilsa. She made it her business to be in everyone else’s business. Once, I stupidly used office postage to send out copies of a book I’d written. Ilsa found the packages strange, opened them, and tried to get me fired in my first month.

Michael O’Connor (editor, 1988–95): Ilsa came in from a temp agency—for Nazi commandant women.

Jerry Rosco (Mandate and Torso editor, 1989–94, 2004–08): Ilsa was the witch from The Wizard of Oz. She made her points with George in little pinch-wad ways.

__ The Mavety staff was appropriately diverse at a time when the same could not be said of mainstream publishing giants.

Andrew Bass: It was folks from all walks of life—straight, gay, male, female, Black, white, Asian, Latino, Canadian, American, Filipino.

Jerry Rosco: There was never any kind of discrimination in the office.... I said that to Mavety and he said, “And there never will be!”

__ Mavety was also a trailblazer for hiring a majority of gay employees to produce gay magazines for a gay audience. But that emphasis had one unintended effect.

Jack Pretzer: A coworker and I had great rapport, and I thought it was cool to have a friendship with another gay guy. One day, he asked me to lunch and said there’s something he wanted to talk to me about, walked me twelve blocks from the office, and proceeded to come out of the closet to me... as straight. He’d been talking to his wife on the phone using male pronouns, afraid to put her on his health insurance.

Aaron Krach (Inches editor, 1999–2001): One Monday, I came in hungover and I was talking with Ben about my weekend and where I’d gone—and he asked me where the Boiler Room was, and I was like, “Uh, every gay person in New York knows where it is.”

Benjamin Tischer (Torso editor, 1998–99): I was totally in the closet the entire time I was there. I would take off my wedding ring when I went to work.

__ But there were limits to Mavety’s progressiveness.

Don Hailer: We had a trans person come in for a week, a temp as a secretary for [nineties editor in chief] Doug [McClemont]. He wanted to hire her, but Mavety said no because of the bathroom. Doug said, “We have that private bathroom at the end of the hall,” but Mavety didn’t want anyone to use it—that was his bathroom.

Freeman Gunter: George had a private bathroom, and along the walls were stacked in retail crates, like from the supermarket, chocolate bars. He would go in there and have a couple of chocolate bars on his way to get lunch.

__ MMG’s most important figure outside of George Mavety was an Asian woman named Virginia Chua, a glass-closeted lesbian who played bad cop to a mellowing Mavety’s good cop. “He let Virginia do all the dirty work,” Phil concedes.

Kerry LaFace (circulation, 1998–2004): It was like The Devil Wears Prada—when Virginia is walking down the hall, everyone is scrambling.

Andrew Bass: Sometimes I wondered who ran who, Virginia or George?

Wayne Gray (sales rep, circulation director, 1990s–2003): All these warehouse workers, who were Filipinos, were scared to death of her. If she told them, “You take this $100 bill and burn it,” that’s exactly what they would have done.

Michael O’Connor: She was always in pastel pantsuits—pink, lime green. We were not supposed to know she was gay.

Gordon Wallace: Ramon in typesetting, who was gay, told me a gay guy in editorial went up to her and said, “It’s so great you’re gay!” and she fired him on the spot.

Dian Hanson: She was Chinese heritage from the Philippines.... She had a Filipina girlfriend who was a ping-pong champ or something and always made it clear that she thought she was superior to her girlfriend because of her Chinese origin. She told me once in the bathroom she really wished she had eyes like mine. I was like, “You could get blue contacts.” She said, “No! Big and round.” Then she had a falling-out with the girlfriend and got this white girlfriend, and it had a huge effect on softening her. It was like this was the prize she always wanted.

Some employees’ families, friends, and peers thought knowing someone in porn was titillating, some thought it was funny, and others thought it was a character flaw.

Andrew Bass: Growing up in Brooklyn, folks had very definite preconceptions on the gay community. I had to deal with my dad because of that. He questioned why I [as a straight man] would take that job in terms of maybe there were some inclinations on my part.

Richard Rosenfeld (illustrator, 1970s): There was one client in the fashion industry who was gay and would not use me because of my work in the gay magazines.

Jery Tillotson (writer, 1978–’90s): I went to a poetry reading at A Different Light bookstore, considered the biggest bookstore in the world for gay writing. At the wine-and-cheese party, I said, “Oh, I’m writing stories for Mandate.” “Oh, you’re writing garbage.”

Kerry LaFace: Twenty years later, I ended up moving back to the town I grew up in, and when I see some of the guys I grew up with, they still call me the porn queen. That’s forever what I will be associated with.

Mickey Squires (model, 1970s–’80s): When my mother was in her nineties, I said, “Mom, I have to tell you, I was on the cover of gay magazines.” She said, “Of course you were on the cover.”

Working for a print porn company in the nineties was not the bacchanalian orgy you might envision. But in the eighties...?

Dian Hanson: The end of 1986, the office was out of control. It was an almost entirely gay staff having parties at night there. Guys were running around in little cutoffs with their balls hanging out. I came in the second week of work and found dried spooge all over my typewriter.

__ Things began to change with the move to 462 Broadway at Grand at the end of the decade. Art director Tom Cicero recalls George Mavety telling him early in his tenure, “I don’t know what you’ve heard, but you can’t have sex on the tables now.”

Even when overt partying was curtailed, the atmosphere could still be sexually charged. There was a Latino mailboy with soulful eyes who wore a suit and was rumored to have seduced more than one of the women in the office... in the office. He wasn’t the only one who broke the rules.

Michael O’Connor: One day, we had repairmen in there, an old guy and a young, hot guy. At the editorial meeting, the young one asked if he could come use my phone. He left, and I jokingly said in the meeting, “I have a date!” Well, oh my God—he likes older men and he’s gay and the whole thing was a pretext. He wanted to be tied up and maybe wear women’s underwear. I don’t remember if he used my phone.

Cheewai Yip: Believe it or not, we had interns. There was this vanilla white boy, still in college, and [someone on the business side] would always say, “He’s taking one of the magazines, going in the bathroom, and whacking off.” You could hear him. He had a recharge that was impressive.

__ Contact between staffers and models was rare (Mavety forbade any photo shoots on the premises to shelter himself legally) but not nonexistent.

David Henry (Torso art director, 1985–87): Jeff Stryker would come in; Leo Ford would come in. What were they like? Short.

Tom Cicero: Jeff Stryker sent me letters asking to be in the mags and said he would fly to New York to fuck me as a thank-you.

Michael Llewellyn: My friends would ask, “Do you sleep with the models?” The only one I ever slept with was on Mandate’s first color cover, a male nurse from Mississippi who took the magazine to work—he was very proud.

Chiun-Kai “Chunky” Shih (photographer, 1996–2001): I shot Mr. Leatherman of the Year. He had a big ring on his dick and was so beautiful. He was the first person to grab my hands and say, “You’ve got the perfect hands.” I found out he meant for fisting…. Doug [McClemont] took me to an award show in Paris! I never was top or bottom at that time; I was just a boy that jerked off. I really liked Steve Rambo. In the middle of the night, I was sleeping in the same hotel room with Doug, and Doug says, “You’re tossing and turning, you can’t sleep—let me see your dick. God, you have a huge dick for an Asian boy.” He said, “You gotta go downstairs, knock on Steve’s door, and tell him I said for you to do it.” I did, and that was the first time I ever slept with a porn star. I came like four times.

Ken Tirado (Juggs, Leg Show, and Honcho designer, 1985–88): The only celebrity I saw in the office was Candy Samples, a stripper and adult movie star. She was the mascot of Juggs. She came to the city for a win-a-date contest. Guys sent in Polaroids of themselves and would handwrite, in primitive scrawls, essays why Candy should pick them. You’d be surprised how many pictures we got of West Virginia coal miners with their dogs.

__ By the time I arrived in the mid-nineties, Mavety Media was distressingly corporate and had an even more sedate Cranford, New Jersey, office, which was—in stark contrast to Mavety’s magazines—in the closet.

Erik Schubert: We went to Cranford for [George’s] birthday one year. It was a weird office in a strip mall, and you’d never have any idea what the business was from outside.

Tanya Wood (head of circulation, COO, 1990s–2001): Don’t you think the neighbors would’ve had protests if they’d known?

__ It was often joked that if you worked in porn, you could never sue for sexual harassment. “There was no way to complain about that,” says Kerry LaFace, who worked in circulation in the Cranford office. Mavety was her first job out of college, and she had arrived “a very good girl—I’ll put it to you that way.”

Kerry LaFace: We were so grossly inappropriate. When we moved to the Cranford office, Tanya needed a secretary. She hired a mom who had been out of work and... we’d open a copy of Black Inches, hang it over the wall, and be like, “Ever seen one of these?”

David Henry: I was eighteen. I got hit on... my fourth day of work. There’s this super-gay restaurant in West Hollywood called Mark’s, and it’s really dark. I remember [a manager was like], “Let’s go to lunch!” I think I had only three Long Island iced teas. The party kept going. He drove me back and in the parking lot asked me if I would sleep with him, sitting in the rented 450SL.

Gordon Wallace: I remember a guy had bought presents for everybody. [A guy from legal] said, “I wanted to give you a blowjob, but I couldn’t figure out how to wrap it.” I immediately ran into the office to say, “You don’t have to put up with this shit.” The same guy once said about a model, “I’d eat a mile of shit to get to that asshole.”

David Henry: It’s midnight and we’re back at someone’s apartment in West Hollywood, and a giant pile of coke is being passed around on a mirror. I put it on my knees to do a line and drop it all over the rug, and I had that one second where I was like, “Is this how I’m gonna die?” They were like, “Don’t move!” and got on their hands and knees and snorted it off the rug, my shoes... my jeans.

“I wouldn’t want to give in to censorship,” Mavety crowed to OutWeek in 1990. “I consider myself a liberal thinker, and a maverick in my own way.” But unlike Larry Flynt, who was shot and paralyzed while fighting for his First Amendment rights, Mavety had no interest in doing time—and frequently scolded staff members pushing for edgier content by insisting he didn’t want to end up in a chair.

George De Stefano (Mandate editor, 1982–84): He saw himself as this pro-gay civil libertarian and free-speech crusader against censorship because he had a fair amount of legal trouble in certain states, so he had this image of himself as not just a crass businessman.

__ The photography was nude, not lewd, and while the text was hardcore, both had to adhere to a mass of rules.

Tanya Wood: The biggest [rule] was [no] penetration.

Erik Schubert: If we were gonna be in a Walmart in a podunk city, that community’s standards decided everybody’s standards.

Tom Cicero: We were fighting to show two guys together in a magazine, touching, and it was “No, we can’t do that because of the laws....” George brought this up to his lawyer, who was probably eighty-five, and he’d say, “If a man is holding his penis from the base, it’s okay. If he’s holding it at the tip, he’s masturbating.”

__ The authorities never nailed Mavety but weren’t above dabbling in a little alleged entrapment.

Jack Pretzer: Once or twice a year, I would be at my desk and get a call, and it would be this obviously heterosexual man breathing heavily and asking me if I could put him in touch with [the pedophile organization] NAMBLA, and I would just laugh and hang up.

__ To balance the magazines’ filth factor, nonsexual content had to be prominent in every issue. It was called “socially redeeming,” as if a second-rights interview with Ann-Margret might erase the sin of visible penises.

George De Stefano: I edited articles and porn fiction but did a lot of gay political writing for them, features on the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence and the gay movement. As long as we kept the porn flowing.

Owen Keehnen (writer, 1992–97): I did Q&As with John Preston, Paul Monette, Michael Cunningham, Edmund White, Holly Woodlawn, James Earl Hardy, and David Leavitt. Samuel Steward was always at home. Quentin Crisp was in the phone book.

Gerry Geddes (writer, 1982–92): One of my best friends was artist Robert W. Richards, my Uncle Mame. For Torso, they asked him if he wanted to do a column—he was witty and finger-on-the-pulse—him illustrating and me writing. The joke used to be “I read Playboy for the articles.” We were “the articles.” We wrote the first article about Cyndi Lauper and were also the first to attack Eddie Murphy when he started being homophobic in his routines.

__ Not even socially redeeming features were immune from drama.

Gerry Geddes: Joan Rivers was on the ascension, so Robert drew this beautiful picture of her and ran it with a diagram of all the surgical things done to her face. A card company contacted us and said, “We would love this to be a card.” Joan Rivers’s lawyers called and said, “We’re gonna sue if you do this.”

Michael O’Connor: Mr. Mavety had one gay friend who used to whisper to him every few months: “Too many Judy Garland articles!”

Some people actually did read Playboy for the articles, but for Mandate, getting hot models and making photos of them erotic was what it was all about.

Michele Karlsberg (production coordinator, 1989–92): Joe [Mauro] and Stan [Leventhal] had men come in the office: “Show me your dick.”

Steve Perkins: I had to dig through piles of photographs of naked guys and process them. There was a yes pile, a maybe pile, and a no-fucking-way pile. Years later, it occurred to me I was categorizing guys in real life in piles.

Charles Hovland (photographer, 1986–2009): The magazines looked for three things: a good face, a good body, and a nice dick. People were always asking, “What is your definition of a nice dick?” They had to have a big dick if it was gonna be in Inches, but if it was Playguy or even Mandate, it had to be a reasonable dick... a hard dick.... A great model would show up drunk or they’d just had sex, and it turned into a taffy pull.... I never had a fluffer.

Tom Cicero: Charles never fluffed, but I did. I wanted to see what he went through during a shoot. Someone had applied to be a model: “I can get a hard-on in a second.” But then the guy could not get it up. I decided to take one for the team.

Chiun-Kai “Chunky” Shih: The first model [Doug] gave to me, I fell in love... but he’s 100 percent straight and completely a cockteaser. When it came out in the magazine, I masturbated over my own photographs.

Jürgen Vollmer (photographer and production, 1974–83): I only photographed straight guys—I never had sex in my entire life with a homosexual. I only liked straight guys around twenty.... The only thing in my entire life that I am proud of is that I had so many straight guys that I was able to seduce.... That is the only thing that made my life worth living.

Chiun-Kai “Chunky” Shih: This guy showed up and was really chubby—he needed the money. I photographed him, and later he got published and came back and asked me to destroy any photograph I shot. And you know, as a photographer, that’s a no-no, right? He ended up crying. I said, “I will do the right thing for you.” I destroyed every slide. And he turned out to be the Naked Cowboy in Times Square.

By far the greatest challenge to face the employees and management of Mavety Media—and the gay community in the eighties and nineties—was the sudden emergence of AIDS. Dian Hanson recalls the threat of AIDS “hung over the office” like “a specter of dread.”

George De Stefano: I remember Don Beavers making light of AIDS, like, “This will pass quickly. People are getting hysterical.”

__ Beavers, the vice president of advertising who helped Mandate with a Future Model Contest in L. A. in 1983 and wrote about it for the magazine, died of AIDS. He is a part of the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Michael O’Connor: Joe Mauro, the gay art-department head, died of AIDS. Kevin Grubb, a bodybuilder in typesetting, died of AIDS. The guy who sat behind me died of AIDS; when he was in the hospital, Kevin and another guy from his department would go and help feed him—there weren’t enough nurses to spoon-feed him soup. Adolf Garza died not long after he left.

Dian Hanson: The art director Adolf was in a state of rage that his partner was dying. One day, he came in late and disheveled and said, “I stopped to make some guy blow me in the alley.” I was like, “But your partner is near death,” and he’s like, “Who cares? We’re all gonna die.” And then there were these people who were helping each other. It was this weird environment.

George De Stefano: There was a photographer we used a lot. We did an interview with him about coping with AIDS—he was exercising and taking care of himself—and I had to call his home the following Monday and he had just passed.

Dennis Forbes (Falcon Studios photographer and founding editor of the rival Advocate Men, 1970s–’80s): I think almost all of the models are dead, I really do.

Dian Hanson: There was a handsome Black guy in sales. What I remember about him was his terror. All of his friends got sick and died, and he was the first person I knew who seemingly showed a natural resistance to HIV. He was sure his day was gonna come, and yet it never did.

__ George Mavety now receives mixed reviews for how he approached staff members who were ill.

Dian Hanson: George called me in and said, “We need to get a new art director. How about so-and-so?” from another magazine, and I said, “He’s dead.” “How about so-and-so?” “Sick.” “How about so-and-so?” “Dead.” He put his head in his hands and started crying and said, “What’s going to happen? Are they all going to die?”

Freeman Gunter: My lover David had AIDS, and George was afraid I would get it and he would have to carry me to save face in the gay community. He couldn’t just kick me to the curb, so he fired me on some pretense.

Dian Hanson: He supported every one of them to the end. He kept everyone on full salary up till their deaths.

Christopher Bram (editorial, 1990s): I don’t remember Mavety being helpful.

Dian Hanson: A representative from our new insurance company came in, and the guy looked at everybody and said, “How many people are married?” Two. “How many have kids?” Nobody. Then he kinda looked around and said, “I’d like to talk about sexual orientation,” and George Mavety stood up and said, “Nobody is going to be off the plan because of sexual orientation.”

__ The AIDS crisis took over gay life, so it had to be addressed in the magazines. Should the fiction help eroticize condoms? Did gay men still see Mandate as a lifestyle magazine, one from which they would tolerate safer-sex PSAs?

Michael O’Connor: We had a fiction contest every year. There was one story everyone thought was heavy-duty, about somebody who had AIDS but didn’t look it. The last scene, he was starting to fuck this guy. It was like, “Oh man, he’s killing this guy.” We all decided we couldn’t use it... but it won the contest.

George De Stefano: There was discussion of AIDS early on. In David France’s How to Survive a Plague, he talks about Richard Berkowitz coming to my office. We published Richard’s article—a summary of what would become his pamphlet, but it had all those main points of STDs and about the need to use barrier methods of protection. We did take it seriously.

__ Still, AIDS in Torso was a joke as of September 1984, when letters editor Brian J. O’Hara replied to a reader asking, “What, in your opinion, is the most difficult thing about having AIDS?” Referencing early AIDS demographics and in a voice that echoed the 1982 best-selling paperback Truly Tasteless Jokes, O’Hara responded, “Explaining to your parents that you are a Haitian!”

By the December 1985 issue of the magazine Jock—a Mavety endeavor dubbed “Torso’s Dirty Little Brother”—that flippancy had flipped. After admitting in his “Superbitch” editor’s letter that he had “avoided the subject,” “afraid that bringing it up would shoot the shit out of our sales” and “turn you off,” self-styled bad-boy editor Casey Klinger argued that the magazines existed “to entertain you. Perhaps to offer an alternative to contact sex.”

Bill Baumer, editor in chief of the gay titles by 1987, contributed a number of articles about the disease while fellow employees succumbed to it, but not until February 1987 did George Mavety address AIDS explicitly in the pages of Mandate. In a rare publisher’s letter, he wrote about losing “five dear friends to the scourge of AIDS-related illnesses. The voices I used to hear, the laughter I used to enjoy no longer exists.

“I would be remiss in my duties as a publisher of gay magazines if I did not call your attention to the urgency of this problem.” He encouraged readers to support eight fledgling AIDS orgs, including Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

Perversely, the carnage of AIDS ultimately benefited Mavety’s bottom line.

Kristen Bjorn (model, photographer, and director, 1980s–2009): The AIDS crisis may have created a need for the magazines.

George De Stefano: Mavety—ever with his eye on the bottom line—“How terrible this is!” But I’m sure he thought, Well, this is going to increase sales of my publications because people won’t be going out so much.

__ Stan Leventhal, an aspiring writer who founded the gay Amethyst Press while working for Mavety—doing so with Mavety’s blessing and money, with no financial obligation to his boss—was the most prominent and last Mavety figure lost to AIDS, a year before antiretroviral therapy made HIV survivable.

Michael O’Connor: Stan took an AIDS test and in the editorial meeting said, “I just wanna say I got the test, and it’s a wonderful test and you should all do it.”

__ As the editor of all the gay titles, Leventhal oversaw what went into magazines with combined circulations of over one hundred thousand per month, a coveted position of power. His death forced a changing of the guard that weakened the magazines, and also arguably dimmed George Mavety’s passion for his gay titles.

Stanley Stellar (photographer, 1983–2000s): The whole thing ended for me when Doug-somebody became the editor. I never met anybody worse in publishing.

__ Doug McClemont, the second-to-last editor in chief of the Mavety titles, was polarizing. “Doug, because he went to the scratch-and-claw school of promotion, won—all the authority went to Doug,” a top freelance photographer says today. A deadpan, Warholian presence, McClemont sought to elevate the magazines into art, a tall order for what had increasingly become, by the nineties, jerk-off rags. He made Honcho his pet project.

Tom Cicero: Doug’s take was much more artistic—in his mind.

__ The rebrand was wrongheaded and cost George Mavety a lot of money.

Charles Hovland: It was a huge flop, to the point where Honcho was the lowest-selling magazine. Somebody in small-town Nebraska didn’t care about Jack Pierson or Wolfgang Tillmans—they wanted hot pictures.

__ Things came to a head when McClemont began getting rid of everyone who wasn’t on board with his plans.

Stanley Stellar: Doug looked at me and said, “Oh, of course we’ll still be using you, Stanley. Just... not so much.”

Gordon Wallace: As I recall, he was also generally perceived as paranoid.

Tom Cicero: Doug took the Rolodex away from me, so I knew he was a man who wanted power. When rumors got back to me that [he believed] I was trying to poison him... I’d go into the editorial section and open a Splenda near the coffee so it’d look like I messed with his coffee.

Want more great stories like this?

SUBSCRIBE TO ESQUIRE

Cheewai Yip: [When] Doug was an [associate] editor, he would complain, “I’m not making any money.” Pam [Baker] and I would tell him to stick it out. When he got to control things, he got me fired.

__ Baker, who is Black, was singled out by McClemont, his complaints memorialized in interoffice memos and evaluations that criticized her for being “unprofessional,” “disgruntled,” “extremely vocal,” “belligerent,” and “lazy.”

He axed his former close friend Gordon Wallace. Or tried.

Gordon Wallace: When he fired me, I wrote a memo to Mr. Mavety, who called me. I remember he said something emphatic, like “What was that asshole thinking?!” and said I was unfired.

Matthew Licht: I said to Dian, “Why don’t we tell Mavety you want Gordon to write [the straight title] Tight?” and Gordon wound up with a better job than I had.

Gordon Wallace: One lesson I learned at Mavety for sure is: Watch how badly your friends treat others—because one day, they will do it to you.

__ McClemont himself was fired, but not by George Mavety. By then, in 2000, Mavety was dead.

It was unfathomable to most in publishing that the desire, the need, for porn magazines could go away. Pornography and how men consumed it changed radically with the advent of the Internet, which suddenly offered an endless variety of porn at our fingertips—and instead of $7.99 a month, it was free.

I vividly recall Mr. Mavety telling me around 1998, “Mr. Rettenmund, men will never masturbate to a computer. They want to hold something.”

Benjamin Tischer: Mavety was terrified of the Internet. We didn’t even have it on our computers.

Steven Broadway (illustrator, 1980s–’90s): Once porn appeared on people’s phones in their pockets, that was it.

__ But something else could have been running the magazines into the ground: embezzlement. No one was ever charged with any crime, but many suspected an associate was skimming dollars from the organization.

After Mavety’s death, one exec was frog-marched out of the office with no public explanation, never to return.

Gordon Wallace: I remember when Mavety died. It was like Kennedy. The one weekend I went out of town, I came back to the city and my machine was lit up and winking, winking, winking. I picked it up and every message was, “Can you call me?” for fourteen messages, until I got to Dian’s, who said, “I suppose you know Mr. Mavety died.” I just thought, What does this mean for the future?

__ George Mavety’s death shouldn’t have been surprising. Though just sixty-three, he was morbidly obese. Still, his larger-than-life persona and omnipresence in offices across two states made his passing from a massive heart attack on August 19, 2000, a shocker.

In my journal, I recorded that Mavety had returned from France, where he’d spent time with his mistress, Annette McDonald, who went on to Orlando with their child and her child from a previous relationship. The way his death was described to me at the time—everyone has a slightly different memory—was that George played tennis and returned home, where he spoke to Annette by phone. Experiencing chest pains, he said he had to call her back, then died in his housekeeper’s arms. According to my notes, everyone was too scared to tell Annette that George had died, so she returned to New Jersey as planned the next day. His staff knew before his partner did.

Three days later, his lawyer, Debra Lynn Nicholson, spoke to the assembled staff in N. Y. C. “We all lose,” his shocked brother Phil muttered as she spoke, telling us George “loved women. All kinds. Big butts, big boobs, all shapes and sizes. He built an empire on that.”

Conspicuously absent from Phil’s comments and Nicholson’s speech was any mention of the gay titles that had been the cornerstone of Mavety Media but that had begun losing money.

Tanya Wood: I heard him say a thousand times, “Miss Wood, if and when something happens to me one day, I’m going to laugh because they’re all gonna be fighting over it!”

__ His will was, in fact, contested by at least one party—his mistress, Annette. Her suit was dismissed, leaving her with $200,000. (A previous mistress received $500,000.) Mavety left $1.5 million and a family home to their son and $100,000 to her son by another man.

Mavety’s funeral was appropriately over-the-top. Held on the afternoon of August 24, 2000, at St. Peter’s Church in N. Y. C., the service featured eleven speakers, including disgraced former U. S. congressman from New York Mario Biaggi and then–U. S. representative Charlie Rangel.

My diary records that Nicholson semi-roasted Mavety, saying he had plucked her, as a young lawyer, from doing local work in Sparta, New Jersey, to wine and dine her, sending her to Europe to “further my education.” Asserting he’d always sent her first-class on the Concorde, she noted that people began to gossip about their association. “I was thirty-nine—far too old for George to be interested in,” she wisecracked.

Gordon Wallace: The front was taken up by his offspring, from youngish middle age to tween. I had to vacate my seat to make way for a mistress who was weeping hysterically and being wrangled by two ushers. She was flailing around like a fresh-caught fish. Down in the front, there was this giant urn. For the longest time, it did not occur to me that that urn was Mr. M.

__ Mavety’s memorial included Lucio Quarantotto’s “Time to Say Goodbye,” a fitting sentiment for the end of a man’s life, and for what was coming into focus as the end of an era in gay history and publishing, not to mention a time one year before 9/11. The Twin Towers fell not far from Mavety’s SoHo offices. It would be a number of years before Mavety Media went down, but it was a steady descent aided by a leadership void and renewed Mafia fears.

Tom Cicero: Mavety was dead, so there was no one in charge.

Dian Hanson: I got a phone call, and Virginia Chua told me, “George has just died. We’re gonna have to pull together and run the company.” It was Tanya Wood, who was head of sales, Virginia, and me. We thought it was going to be like a women’s coalition. But then [others] contacted Phil up in Canada, and he came in, and their first order of business was dragging Virginia out of the building.

Tanya Wood: Mrs. Mavety was to oversee the business should anything happen to him, but she had been going through cancer treatments when he died. Phil was a plumber by trade.

Dian Hanson: I didn’t wanna talk to anybody about it because mobsters had threatened me, so I just faked a nervous breakdown and got out of there.

__ Virginia Chua’s firing and Hanson quitting felt like Mavety dying a second time.

With the company still in upheaval after a year, 9/11 added a surreal chapter to the Mavety story. The Twin Towers were visible from the offices on the edge of Chinatown.

Don Hailer: The office was closed two days, and I think we were able to get in that Thursday if we showed ID. I remember a memo: “We understand it was a horrible experience, but deadlines are very important, so we all have to put in 110 percent.” I thought, Fuck you.

George Mavety was dead. The market for softcore porn was dying. Print was on life support. And yet the company Mavety left behind trudged on for more than a decade.

Phil Mavety: In retrospect, it should’ve been closed down in the first four, five years [after George’s death]. So many different people were involved—lawyers, accountants. In the end, they’re all working for themselves.... Everybody wanted money. There wasn’t one person that didn’t ask for more.

Gordon Wallace: When I took over, the situation was royally fucked. I brought sales up, but we had a dying readership.

Charles Hovland: One day, Gordon called and said, “That issue on the stands now? That’s it.”

__ On May 11, 2009, I broke the news at BoyCulture.com that Mavety Media was pulling out of publishing. The process would take several years, but, at the time of the announcement, all of Mavety’s iconic gay titles were still in existence, surviving Mavety himself by nearly a decade.

Dian Hanson remembers, “He once told me, ‘My accountants are telling me I should shut down the gay titles, but the gay titles are what I started with, the gay titles are what made my fortune, and I will never let them go.’ ”

Even in death, he stayed true to his word. That unbudging vision is why, for all of Mr. Mavety’s shortcomings, I agree with the magazines’ most important editor in chief, Sam Staggs: If Mavety were alive today, I’d seek him out and kiss him on both cheeks.

Want more great stories like this? Check out "The Rise and Fall of Playgirl."

You Might Also Like