How Polari, the ‘lost language’ of gay men, inspired much of the slang we use today

In an episode of Hulu docuseries “The Kardashians,” matriarch and momager Kris Jenner posed a prescient etymological question to her daughter Khloe Kardashian in the midst of getting all dolled up.

“How do you spell zhuzh?” Kris asks the room, as Khloe’s glam squad flits about. “Like, when you zhuzh something.”

“Zhuzh?” Khloe responds. “I don’t know, is that a real word?”

“This isn’t an actual word, first of all, that you learn in school,” a member of their entourage claims. “Maybe in gay school.”

In the clip, Kris asks her iPhone several times how to spell the word to no avail — speech-to-text regularly mishears the the word as “judge” or “George,” so it’s not Kris’s fault.

Regardless, “zhuzh” — the pronunciation sounds a bit like "jouj" — is in fact a real word, meaning “to fix, to tidy; to smarten up,” according to Green’s Dictionary of Slang.

This word is one that has a long history as part of a centuries-old language, Polari, a slang language which was popularized by such disparate populations as circus performers, sailors and queer subcultures long ago.

Polari, which is also spelled Palarie, Parlary, Palare and various other ways, is directly responsible for creating or popularizing some of pop culture’s biggest buzzwords.

Butch, femme, drag, camp, zhuzh and more are now in common parlance, thanks to Polari, as well as some quite spicy terms, like cherry, dish and more (but more on that later).

Still, as widespread as a selection of these words have become, the language’s history is all-but-forgotten by the wider culture — or more likely, was never learned at all.

Polari is the source of the above Kardashian moment, yes, but also 2019’s Met Gala theme, “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” plenty of “RuPaul’s Drag Race” moments — including the show’s title — and so much more.

To find out how we got here, let me take you to, well, “gay school.”

Polari’s origins

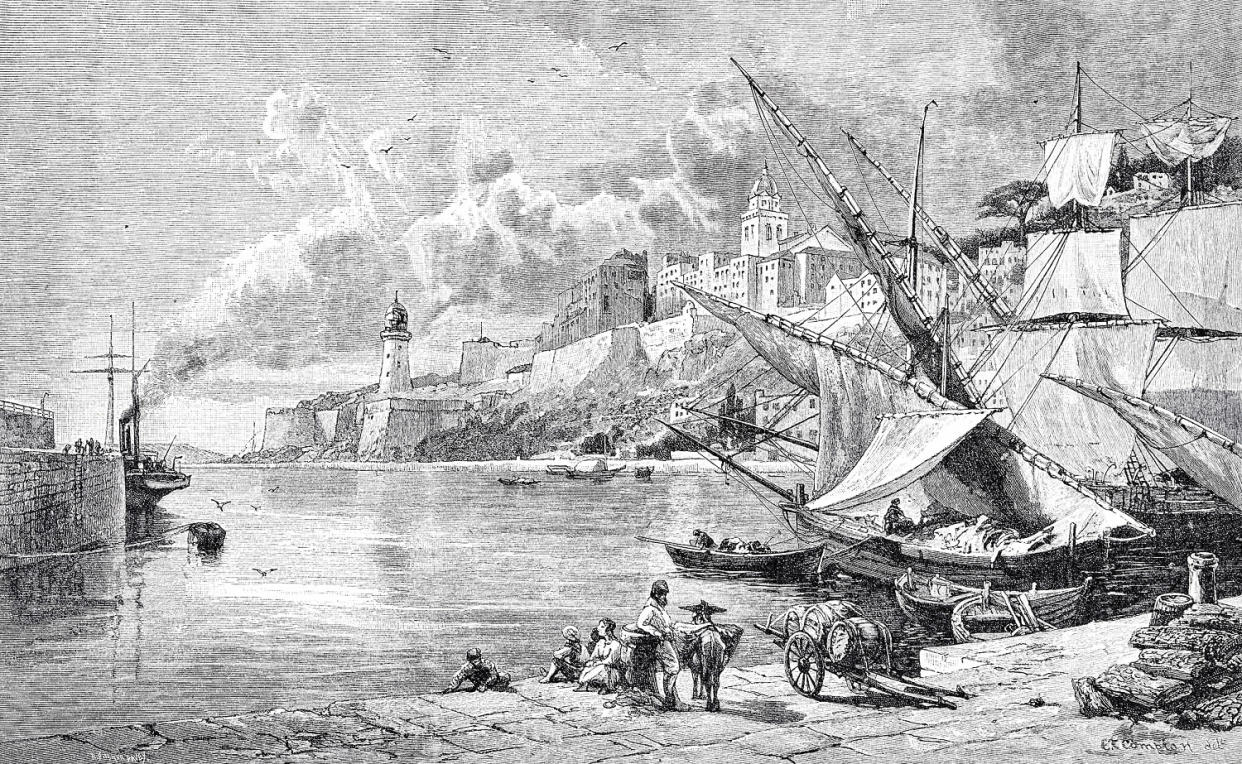

Polari is widely believed to have originated in Mediterranean ports around the 16th century to the 18th century. Sailors who spoke different native languages used a form of it as a common shorthand to avoid having to learn every other language spoken at port, experts say.

“It was a trader’s jargon or a cant, as they call it, which is this lingo used by people who work the ships and the brought cargo from place to place in Europe and in the Mediterranean,” says Grant Barrett, a lexicographer and linguist specializing in slang and new words.

As the language grew, so did the categories of people who used it: In addition to sailors, vagrants and traveling circus performers relied on it, many of them from or influenced by Romany culture. In fact, a lot of Polari words derive from the Romany culture as well as facets from Italian, Indian and other tongues.

“It’s a kind of a mishmash of other languages. We know, for example, where the zhuzh is very similar to Romany words meaning ‘to clean,’” Barrett says, pointing to the Angloromani words “yusho” and “yuser.”

The language eventually made the journey to the U.K., as it was particularly popular among actors and queer men in the Merchant Navy, some who would dress in drag at sea. Eventually, it shifted into its most recognizable form as a language used by LGBT people during the early 20th century.

Polari was used in secret

Barrett hosts a language-focused podcast called “A Way With Words,” which recently dealt with the spelling of “zhuzh,” when a caller, like the Kardashians, had no idea how to spell it.

“It’s a common question,” Barrett says. “It’s a fun word to say.”

The word has several spellings, actually — tszuj, zhuzh, zhoosh, jhoosh, jeuje and even josh. This is because while Polari is an extensive language, it was mostly spoken out loud by folks who weren’t too keen on writing it down — and for good reason.

Paul Baker, author of “Polari: The Lost Language of Gay Men,” wrote that the language emerged in part from the slang lexicons of numerous stigmatized groups, which made it a popular option for queer folks who could not live openly at the time.

Baker, who is a professor in the Department of Linguistics and Modern English Language of England’s Lancaster University, wrote that Polari was used in order to maintain secrecy, but also as a means of socializing with like-minded people in a safer way.

“Polari was a way for gay men to talk to each other, but also to create a sense of solidarity and a sense of community, just like a lot of repressive languages,” Esteban Touma, cultural expert and language teacher at Babbel tells TODAY.com. “It was a way to not only establish contact, but also to support each other, and in that way, express themselves and their identities in a covert manner, since it was illegal at the time.”

In the 19th century in England and Great Britain, sodomy remained a capital offense punishable by hanging until 1861.

By the start of the 20th century, gay men were potentially able to be kept in penal servitude for life or for any term not less than ten years by the laws at the time.

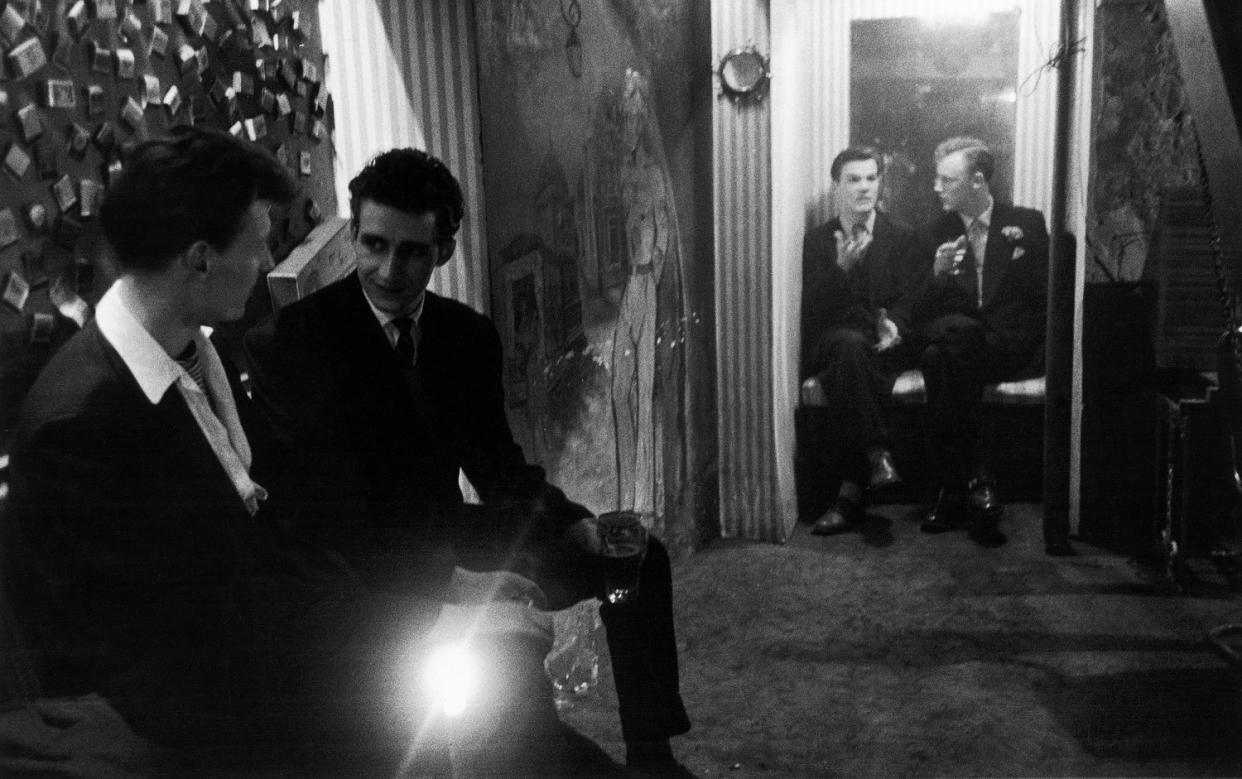

Even royalty wasn't safe from persecution: In 1954, the English Baron Edward Douglas-Scott-Montagu was convicted along with Peter Wildeblood and Michael Pitt-Rivers for homosexual acts and sent to prison.

Although a lifetime of servitude was less severe than death, it was still a permanently life-altering punishment, so it makes sense that no one was writing anything down. Still, that doesn’t mean Polari speakers weren’t having any fun.

A coded language for sex

It must go without saying that since gay men and women were stigmatized because of who they were attracted to, a lot of Polari words have to do with sex. Plenty of words were conceived for cruising, adult activities and sexual identities, such as the often pejoratively-used fruit, fairy and pouf.

“As well as being funny, gay slang is often subversive, assigning bold new meanings to words that already exist, tackling taboos and laughing in the face of adversity,” Baker wrote in "Fantabulosa: A Dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang.” (Fantabulosa is actually a Polari word meaning wonderful.)

Words like cherry, dish, tart and many other food-related words were used to describe sexual acts while making it seem to the casual observer you were just talking about lunch. Even words for innocent things like eke, which means face, were ways to clue one another in that you were part of the club.

“The fact that these words spread is not only a matter of saying, ‘Oh, this is a cool new word,’ it’s also a matter of saying ‘I am part of that community, I am part of this language,’” Touma says.

Baker wrote in The Guardian that Polari was often used sarcastically or as a way to throw shade. This included inventing feminizing terms for the largely male group (at the time) that persecuted gay populations: the police. Thus “Betty bracelets,” “lily” and “orderly daughters” all meant police in Polari.

Polari words spread, as the language itself faded

On March 7, 1963 a radio show called “Round the Horne” premiered on the BBC. In Episode 4, the popular comedy program introduced Sandy and Julian, two characters played by Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams.

“Now, if you’re listening to them with a modern ear, you hear these very gay vibes,” Barrett says. “At the time, I think many people did also pick up on that, but they had this kind of lingo that was just stuffed with the language of theater and the arts and a lot of it was Polari words.”

“How nice to vada your eke again,” Williams says as Sandy in the episode, using two Polari words: vada (to look) and eke. Later in the episode, a reference to someone’s “package” is spoken by one of the characters, to raucous laughter from the audience.

Both actors were members of the LGBT community, performing in a time that being gay was illegal. The show was extremely popular and boasted an audience of 9 million listeners a week.

Barrett says words like drag for wearing clothes of another gender or camp to mean excessively showy behavior or appearance came from Sandy and Julian popularizing the terms to the UK audience, priming it to spread beyond its shores.

As these words grew in popularity, so did the idea that love is love among the British people. In 1967, the Sexual Offences Act was passed in the UK, decriminalizing private homosexual acts between men over 21. (The law was not changed in Scotland until 1980 or in Northern Ireland until 1982.)

Polari’s legacy

Even as over the years Polari fell out of use, Britain’s tradition of camp and comedy kept it alive in plays, movies, film and more.

In a 1973 “Doctor Who” serial called “Carnival of Monsters,” a character attempts to converse with the Doctor in Polari.

In music, iconic British singers have sung the language into history.

"So bona to vada, oh you / Your lovely eek and / Your lovely riah," former The Smiths frontman Morrissey sings in "Piccadilly Palare," a song about male prostitution in London released in 1990.

To translate the above, knowing the words bona (good), vada (look), eek (face) and riah (hair) means Morrissey is singing, "So good to look, oh you, your lovely face and your lovely hair."

David Bowie also sung in Polari, using the words "titi" (which means “pretty)” and “nanti” (or, “no”) in the lyrics to his 2016 song "Girl Loves Me," off the album "Blackstar."

And, where would Polari be today without the queens on one of the most popular competition shows airing today?

The Emmy-winning juggernaut that is “RuPaul’s Drag Race” brought several Polari terms into the mainstream.

For example, regular watchers see the queens (another popular Polari word) discussing at least once every cast rotation which one of them is the “trade of the season” out of drag.

The word trade is defined by “Fantabulosa” as a casual male sexual partner — essentially a male hookup or one night stand. Historically, it also referred to sex work, as in "trading" money for services.

Over time its definition has evolved (including in communities of color) to be more simply defined as a male sexual partner who is — or at least, looks — straight.

Coincidentally, Carson Kressley, a frequent Drag Race judge, popularized the word “zhuzh” in a style sense on the original “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy,” which aired from 2003 until 2007, a tradition Jonathan Van Ness continued on the reboot of the makeover show.

Kressley still uses it to this day in speech and even as a hashtag on his Instagram, bringing Polari into the digital age. That's pretty fantabulosa.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com