‘Play It Loud For Him’: Remembering Jeff Buckley and ‘Grace’ at 30

Jeff Buckley once told his manager, Dave Lory, that he wanted to make 18 albums in three years. Sadly, he only made one before he died in 1997.

More from Spin:

The first time Lory met Buckley was in a coffee shop on St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan. It was a Sunday morning in 1993. Buckley had already signed with Columbia Records—the premier label of Sony Music Entertainment—and was being managed by lawyer George Stein, who had no experience with rock acts. Buckley’s EP, Live at Sin-é, was set to be released in a month, followed by a promotional tour, and they needed to find someone fast. At this point, Buckley was still relatively unknown, but Columbia had big plans for him. Lory had just finished producing the New Music Seminar, the largest music conference in the world, and was exhausted. He was hesitant to even take this meeting but obliged Stein anyway.

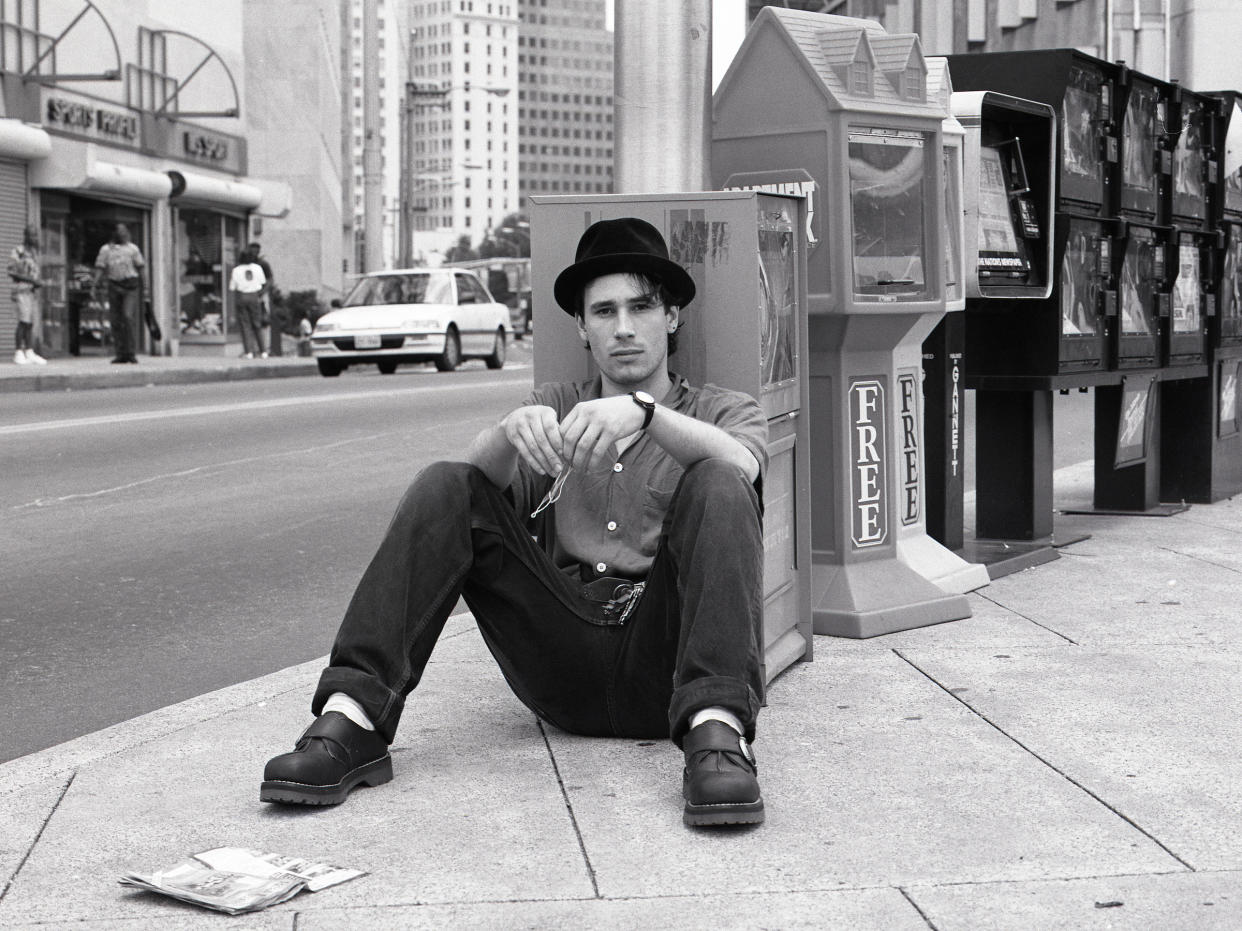

Buckley kept Lory, who was there with Stein, waiting for 45 minutes before he showed up wearing a V-neck T-shirt, black jeans, scuffed-up Doc Martens, and a fedora. Lory tells me over the phone that he threw his manager bio down on the table, and as he walked out of the door said to him, “I got a pet peeve with people being late.” As Lory walked down the street, Buckley followed him and said, “You didn’t kiss my ass.” Buckley, apparently, was used to being courted by music industry professionals who saw potential—and dollar signs—in him. His electrifying solo performances at Sin-é were causing quite the stir; his hypnotic voice, the kind of voice that comes along only once in a lifetime, accompanied by his borrowed 1983 Butterscotch Telecaster guitar. Lory told him, “If I were you, I’d be worried because they are going to chew you up and spit you out.” Columbia, Lory tells me, had a habit of doing that to new artists at that time. He had heard the hype about Buckley, and as they went back inside and began talking again, Lory agreed to manage him.

Steve Berkowitz—the A&R executive and producer with Columbia Records—along with other top executives at the label, chose a release date of August 23, 1994 for Grace.

Famed producer Andy Wallace was chosen to produce the album. Wallace, who had extensive experience mixing Nirvana’s Nevermind and Sonic Youth’s Dirty, and a slew of other well-known records, wanted the production to be casual. He wanted to capture a body of work that Buckley could choose from, with little direction from him. There was no template, no plan for what the album was supposed to look like, or how it was supposed to sound. Because Buckley was influenced by so many styles of music—from Bob Dylan and Led Zeppelin to Billie Holiday and Nina Simone to Eastern musicians such as Qawwali legend Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan—Columbia allotted him the luxury not often given to artists. “He was into so many different types of music,” says Lory. “And to Columbia’s credit, they allowed him a year to just figure out what he was going to do. What record company would do that?”

Recording for Grace took place at Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, New York. Chosen for its isolation, it was the ideal place for Buckley to create with no distractions. Once they arrived, Buckley and Wallace had six weeks to record the album.

By the time Live at Sin-é was released on November 23, 1993, Buckley and Wallace had brought in two permanent band members to accompany Buckley on Grace—Mick Grondahl on bass and Matt Johnson on drums. Gary Lucas was recruited as a guest musician for three days to play guitar on two original songs—“Grace” and “Mojo Pin,” which ended up being the opening tracks of the album.

“It was kind of magical,” Lucas tells me. “I enjoyed playing on the tracks. I doubled the parts, all the main riffs. He left me alone on the last morning to add space guitar…I blew through both ‘Grace’ and ‘Mojo Pin,’ just improvising all sorts of little voices.”

Buckley had met Lucas while playing a tribute concert for his father, singer-songwriter Tim Buckley, at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn in 1991. The two eventually collaborated, and Lucas invited him to play in his band, Gods and Monsters, which Jeff did briefly.

Lucas sent two songs he had been working on to Jeff, who was still living in L.A. at this time, prior to moving to New York. One was called “Rise Up to Be” which would become “Grace,” and the other was called “And You Will,” which would evolve into “Mojo Pin.”

“After about a week, I had two finished instrumentals,” Lucas says. “I could, in my mind, hear Jeff’s voice on them. I didn’t hear a melody specifically. And I just thought they were in the range. He could really work out his voice… against his guitar music. He gets them a few days later, and he calls me and he says, ‘They’re beautiful. Listen, I’m coming to New York in like two weeks, three weeks, and I’ll come over and we’ll work on these.’”

Buckley had gotten a gig to play at premiere parties in L.A., Chicago, and New York for the film The Commitments. He was hired as a guitar player and a tech for Glen Hansard of the Frames, who played Outspan Foster in the film. When Buckley arrived in New York, he jumped off the bus, met with Lucas, and said, “You know those two songs you sent me?” Lucas tells me that Buckley started playing the two songs, but Buckley had added lyrics to them. “This is the beauty of my working with Jeff,” says Lucas. “He would respect these instrumentals and weave a melody and a vocal that fit the parts I’d come up with like a glove. But then he added these beautiful, sinuous melodies on both these things. With a guy like Jeff, he was like, for me, a dream collaborator because I thought, whatever I hand him, he’s going to come up with the right stuff to fit and it’s going to be beautiful.”

After six weeks in Bearsville, Buckley, Grondahl, and Johnson returned to New York City. Nine songs were almost complete. Three of them were covers: Benjamin Britten’s “Corpus Christi Carol,” “Lilac Wine” by Nina Simone, and Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” The others were Buckley originals, including “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over,” “Last Goodbye,” and “Eternal Life.” “Dream Brother” still needed lyrics and mixing.

But Buckley was struggling with the latest mix of one of those songs. “Forget Her,” about his breakup with ex-girlfriend Rebecca Moore, was a song that Columbia Records loved and wanted for the album’s second single. But eventually, Buckley decided he didn’t want the song on the record at all. (Eventually, it would be included on the 2004 Legacy Edition of Grace.) This meant that Buckley would need one more song to complete his album.

Michael Tighe—who knew Buckey because the singer would occasionally babysit Tighe’s younger brother—was brought in to add additional guitar to the album at Sony Studios in Hell’s Kitchen.

“I was still in high school when I met Jeff,” says Tighe. “We became fast friends…and I had just started playing guitar at that point. He would come over, and we would listen to Son House and Robert Johnson and play guitar together. And then he befriended my family as well. So there would be days that I’d get back from high school and he’d be hanging around with my brother or babysitting my brother and playing with him. It was cute.”

Tighe says when Buckley asked him to join the Grace sessions, it was his first time playing in a band. He had just graduated high school. He remembers playing a composition he came up with on the guitar, one of his first, and playing it for Buckley as they both sat in his bedroom. It was something Tighe said Buckley was really into at the time but never brought up again. But after Tighe joined Buckley in the studio a year later, Buckley mentioned it.

“One day during rehearsal, he was like, ‘Remember that riff you played me last year at your place?” Tighe started playing the chords, and Buckley got behind the drum set and started playing the beat and singing.

“He didn’t quite have the lyrics, but he started singing the melody to the chorus. We recorded the basic track, and he had that melody for the chorus. And then I remember he was like, ‘Okay, I’m going to go take a walk.’ And he took a walk around Hell’s Kitchen, and he came back about two hours later. And this was at like, 1 a.m., and he just went into the booth and in two takes sang all of “So Real.” I was blown away.”

Aside from a few tweaks, Grace was complete.

Lory, along with Buckley and Andy Wallace, officially delivered Grace to Columbia Records on May 31, 1994.

The now-iconic album cover, with Buckley wearing a sparkling sequin jacket—which he bought in a used clothing shop—over a white V-neck T-shirt, his head bowed, and his left hand clutching a vintage microphone, was symbolic, Lory tells me. “Jeff was not a fad. Jeff was Jeff. The purpose of the silver jacket—we call it ‘the Judy Garland jacket’—was for two reasons: Number one was, he didn’t want to define a musical style. And number two was obviously to go as far away from his father as possible.”

To promote the album, Lory and Buckley chose to promote Grace slowly and methodically.

“He and I came up with a plan of ‘one fan at a time,’ and that was getting him out on the road, playing in places that were hip that educated listeners would be at,” says Lory. “And that’s what we did. And we sold out every venue around the world for two years. We started at 40 seats, 50 seats, and you know, by the time it was over—especially international—we were selling out multiple theaters. And we actually turned down a tour with Aerosmith at one point for arenas.”

To help execute this plan, Lory hired Gene Bowen as Buckley’s tour manager to handle logistics, while Lory booked venues and approved all album promotions.

Bowen tells me that Buckley was very particular about the kind of success he wanted from the tour, Bowen says. “And he was not into MTV or into this flashy 15 minutes of fame. He really made it clear to management that if the thing could sell like 200,000 records domestically, that’s all he wanted. Because of his background—his dad—he understood the value of journalists, specifically in Europe, and how journalists were really the “cred” in ways of presenting an artist. Like, if you had the right journalist, that could be the thing that could catapult your career, or if nothing more, the longevity of your career.”

Before soundcheck each night, Buckley did press, from print interviews to radio and TV appearances. Then after the show, the band would travel to the next city and he would do it all over again. Bowen says Buckley felt a lot of pressure from Columbia because, at first, the company was losing money. During its first week, Grace garnered low sales. Critically, it received mixed reviews.

“And college radio wasn’t picking it up, which made me very nervous because we kind of wanted that as a base,” says Lory.

Bowen tells me a story about how Jimmy Page and Robert Plant, in the midst of their “Page and Plant” tour, invited Jeff to open one of their shows. Buckley, a huge fan of Led Zeppelin, turned it down because he felt he wasn’t worthy.

That’s the kind of humility he had, says Bowen.

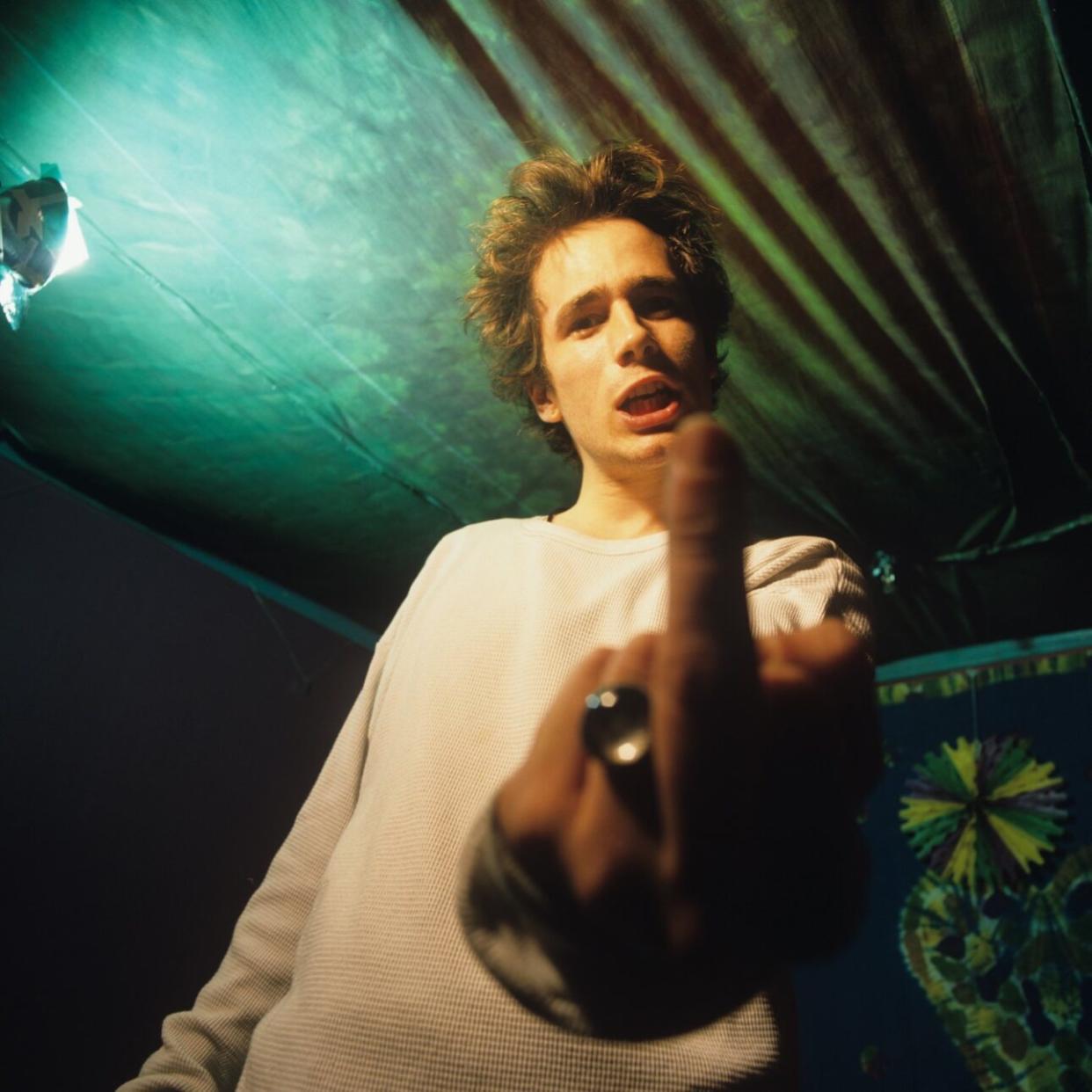

It wasn’t until Buckley played England’s Glastonbury Festival in June 1995, almost a year after Grace was released, that Lory realized the power Buckley could have in large venues and festivals, how he could play in front of a hundred thousand people and make it seem so intimate, almost like his days playing at Sin-é. By the time the tour ended in 1996, Buckley and Columbia Records were making money around the world.

Buckley, of course, never got to see the impact Grace would have on the world. He drowned in the Wolf River Harbor in Memphis on May 29, 1997, at the age of 30. His autopsy ruled it an accident.

Thirty years later, Grace has been generally recognized as one of the greatest albums of all time. Younger generations have discovered the album, raving on YouTube about what a genius Buckley was. If you look on Reddit, you’ll find people discovering Grace for the first time and what that experience means to them.

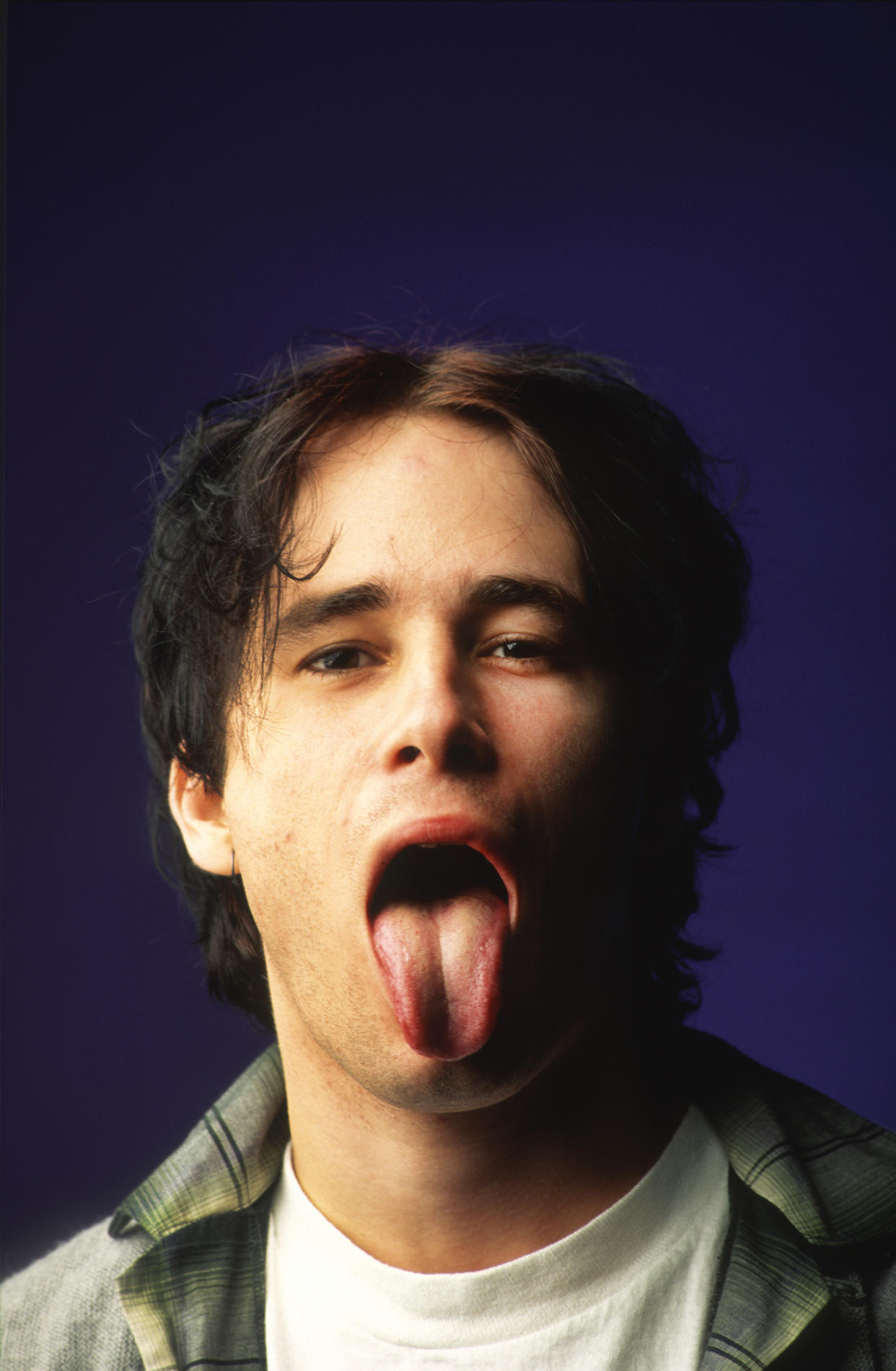

Tighe believes that one of the reasons Grace has endured is because of Buckley’s voice. “I think it really does, like, come down to his voice ultimately,” he says. “He sang from such an emotional place that it almost feels holy, you know? And that’s kind of rare. I actually think Billie Eilish and Frank Ocean sing from that same kind of place; they remind me of Jeff in that way. But there are not a lot of people who can access that. He was ultra romantic.”

Tighe’s right. Watch this clip of Buckey singing “Grace” in the electronic press kit Columbia Records released for the album and tell me you don’t get chills. Look at the way his lips quiver, the way his jaw vibrates as he sings; it’s as if he’s possessed, as if something higher than himself has taken over his body. He was ethereal.

Lory notes that when Grace came out, grunge dominated the American music scene and that Buckley was an anomaly. “Any artist that survives in a career is taking their own path,” he says. “And that’s what Jeff did… When you went and saw him live, it was like a religious experience, and the word of mouth is what made his career happen. What people don’t understand, he was a phenomenal guitar player too. You didn’t hear that necessarily on the album, but you saw it when they played live. And the band was so amazing live that then people went back and listened to the record differently.”

Watch this sped-up version of “Eternal Life” and you’ll see what Lory’s talking about. Buckley didn’t get a chance to really jam on Grace. But he loved to do it onstage with his band, which the label frowned upon. Remember, Buckley was also a metalhead. This was, as Lory tells me, his “Fuck you!” to Columbia.

Thirty years later, Bowen sums up Grace’s legacy perfectly. “I was at a friend’s house the other day, and his kids have a band, and they’re 19 years old,” he says. “And they said at the end they had something special they wanted to play for me, and they ended their set with “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over.” It’s one record, and yet the honesty of who he was has resonated to another generation.

“He’d always say ‘Play it loud! No matter what it is, ‘Play it loud!’ So I always say to people…play it loud for him.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.