My Weekend in the Woods with 150 Trans Men

There were two problems with the assignment: to go to camp as a 37-year-old man. The first was that I didn’t go to camp as a kid, save one two-week stint at band camp in middle school, playing third-chair clarinet. I had spent the bulk of my time at band camp regretting having gone at all and imploring the counselors to let me leave, to no avail. So now, in the lead-up to my three days at Camp Lost Boys, a sleepaway camp for adult trans men like me, I found myself quizzing friends who actually went to camp as children. Asking them things like Is it weird if I bring a suitcase? (“How else would you gather items?” a friend texted back.) “I’m really worried about how I’m going to sleep, pee, etc,” I texted another, who replied, “You and half the other campers.” What do people do at camp? I asked people. Is this supposed to be obvious? Studying the Camp Lost Boys website, I was attracted mostly to a photo of a guy sitting alone meditating. A friend pointed at the archery photo and said I could totally learn to shoot an arrow. I debated inside if this was true. I’ll admit I had been so nervous to go to camp that I had even vaguely hoped the assignment might fall through.

I had met the camp director, Rocco, over Zoom some months prior, snow outside my windows. He was Gen X to my millennial and a notch cooler, if I’m honest—heavily tatted, stylish, L.A.-based. I liked him immediately. He and I discussed the second problem, the bigger problem. How could I describe my three days at Camp Lost Boys without violating the sanctity of the place that Rocco had worked so hard to build?

He was willing to allow me to attend camp in part because I am trans myself, and I didn’t want to be anything other than, well, myself at camp. So during the weekend, I would let the others know I was on assignment for this magazine. I’d scribble incessantly in my notebook (“notes on camp,” I chuckled to myself) but I wouldn’t go out of my way to interview them, or take out a microphone or anything like that. (Anyone whose name you see in this article has given his permission.)

Because, despite the confidentiality that was the camp’s entire premise, I had another, maybe stronger instinct: to tell others, the rest of the world, about our time at camp. To try to describe what happened there, to humanize trans men and whatever our deal is. Maybe I was also still trying to figure that out myself. But summer came fast and there I was, at the eighth iteration of Camp Lost Boys, on the campus of a long-established boys’ camp in rural Pennsylvania, faced with days ahead of nothing but trans men and the question of how to fill my time. Why had I come to this again?

Others expressed nerves too. Rocco alluded to a raft of cancellations that final week leading up. You’d hear throughout the weekend how others had considered driving away or how apparently one guy had pulled in and then just turned around. You had the enormous sense some of us had traveled very far, in time and space and despite a lot, to be here. Guys had driven and carpooled in from all over the northeastern seaboard and from the South and the Midwest. They’d flown in from out West, from Europe. Men had come from Central and South America, from Canada and Australia. On the first night of camp all hundred and fifty of us took the mic one by one by out on the basketball court. Bugs flitted about in the waning light. Each shared how they felt in a word. “Nervous.” “Excited.” “Grateful.”

What were we there for? The word came up again and again: Community. Community. Community.

My carrying around a notebook turned out not to be a problem. Amongst us there were many note-taking types—therapists, professors and the like—so my scribbling didn’t make me stand out. This was especially the case during the various information-heavy sessions and talks—like on trans cybersecurity; one called “10 years after T”; “Dad Chat” for fathers, or those interested in becoming them; “Cock Talk,” for those considering bottom surgery, featuring a panel of others who had. In general, for me and I think for a lot of us, this was the most marvelous thing about being at Camp Lost Boys: For 72 hours, I got to feel so entirely regular.

I felt it in my brain, that first moment I was greeted by a volunteer staffer through a rolled down car window, as he cheerfully explained how to take the COVID test he was handing me. “You nervous?” he asked with a grin. I felt it as Rocco and his co-directors greeted me with their welcoming spiel. I felt it as I met my bunkmates and unrolled my sleeping bag. I felt it as we all anxiously waited for announcements and dinner that first night, making chitchat outside the mess hall.

The place itself was perfect, like a Hollywood set of a boys’ sleep-away camp. The wooden buildings painted brown, the bug-spray-and-sleeping-bag odor of the bunks, the twangy yawn of their screen doors. Lovely mossy paths leading to basketball hoops. Paddle ball and corn hole under the pine trees. For most of the summer a swarm of boys occupies these tiny bunk beds and tiny toilet stalls. Their presence is both spectral and evident in such details as the names of the past camp musicals displayed in the theater or the commemorative paddles lining the walls of the dining hall.

Like me, Rocco wasn’t a goes-to-camp kind of kid; he didn’t know about camp stuff before. Long story short this camp was an idea that became an experiment that became a reality. These days, he’s pleased to say, it’s his full-time job, the larger effort nonprofit. (Rocco had previously done a lot else with his career, including running the first-of-its-kind transmasc publication with the exceptional name Original Plumbing.)

Rocco isn’t that many years older than me in earth-time but he’s been on T nearly 25 years and therefore is an elder to me in a profound sense. To even share space with men like him—let alone men who are in their 50s or 60s or older—is a totally new experience for me. Prior to my weekend at camp I’d been physically in the company of two other trans men simultaneously, total. Suddenly I was around a hundred and fifty and I felt like I was vibrating cellularly. To make casual conversation with men older than me, especially, it was transforming me, I could feel it no question. Maybe until meeting them, I had literally never known what my future might look like.

Decades ago, in the San Francisco Bay Area, when Rocco and his peers were first figuring out how the hell to even receive transmasculine care, I was living only a few miles away from them, albeit in a different world. I was a miserable child, labeled a “tomboy,” simultaneously constantly aware of what was so wrong with me and, in other senses, absolutely clueless. Clueless, at least, that any path existed that could be less miserable than the one I was on. Rocco and his generation of trans men, as well as those before him, figured out how to live this life anyway. Usually it was because they met someone or saw someone.

You were the first trans man I saw on TV, one of the older guys said to another one evening after dinner as we sat at a picnic bench having watermelon and ice cream sandwiches. Our table was discussing when the one had been on Oprah two decades ago. He’d discussed the invasiveness of the host’s questions, how it was, of course, all about whether or not he had a dick. He’d described how the producers of those shows would have you take off your shirt for b-roll, or have you shave the same spot on your face, over and over.

My dinner companion who’d seen the segment twenty years ago reflected that, after seeing him, that was when he felt like, well I have to do something about this—a feeling no doubt all of us here have experienced versions of. He added that before that, he’d only seen trans women on TV, on like Springer. Heads nodded. Another of the men at my table remembered it must have been back in the sixties or seventies maybe when he learned about Christine Jorgensen, an American GI who made headlines in the fifties for being the first publicly known trans woman to have medically transitioned. My dinner compatriot recalled how, having learned about Jorgensen, he’d tried to find out if such a thing were possible, you know, in the other direction. At that point, the answer he got was no. What he’d heard was, oh, it isn’t going to be convincing. Again heads nodded.

The man who’d been on Oprah back then, whose name is Aidan Key, has made many such appearances and spent his career facilitating trans community. He reflected that the one thing he wouldn’t want now is people asking him why he made himself so visible, back then.

It’s something I think about a lot, too: Why risk visibility? You do so in large part because you know there are others out there who need to see this or hear that. Maybe who’ve waited their whole lives to hear you or see you reflected on their screen. But you do so at your own peril, and often with little control, especially back in the day.

Millennials like myself and those who are younger, us raised somewhat or entirely online, we might not realize how rare a thing any media exposure once was for trans people, let alone the sort where you were treated with respect. Because “media” meant—and more or less still means—cis media, and the trouble with cis people, sorry to generalize, but cis people, alas, are often first and foremost obsessed with our genitals. Cis people so often have to undress us in their minds the moment they discover the “truth” of us, our “secret,” what have you. (A recurring joke at camp: imagine if you learned some dude was cis and your first question was, “Oh, are you circumcised?”)

These days, there is the scary sense that the stakes—and the price of silence—have never been higher. Some men this weekend had driven in from states whose names are now synonymous with hate. Many of us live in places, and here I’ll include myself, where we don’t feel safe to interact with whoever we encounter or whoever might swing by. I have to perform an endless mental calculation about which strangers are safe, about where it’s safe, about how I might want to costume myself or behave so as to ensure my safety. A few guys this weekend will speak about how they live stealth, entirely or partially. Not out at their jobs. Not out to their neighbors or partners’ families or their kids.

Because, to really emphasize that even I felt this: Some of these guys you’d never fucking know. You’d never know. Truly. That was perhaps the most surprising feeling, encountering so many trans men who, even to me, did not “look trans.” Whatever expectation I had about how we look radically expanded: There were men of all size and shape and color, all manner of appearance and vibe. Men who aren’t just tall-for-trans but legit tall. Men who are ripped, totally jacked. Men with facial hair, beards of all sorts—goatees, chinstraps, mustaches. I couldn’t help but fixate especially on the beards, three years on T that I am, with my patchy growth, especially on the big full beards—how voluminous, how magnificent.

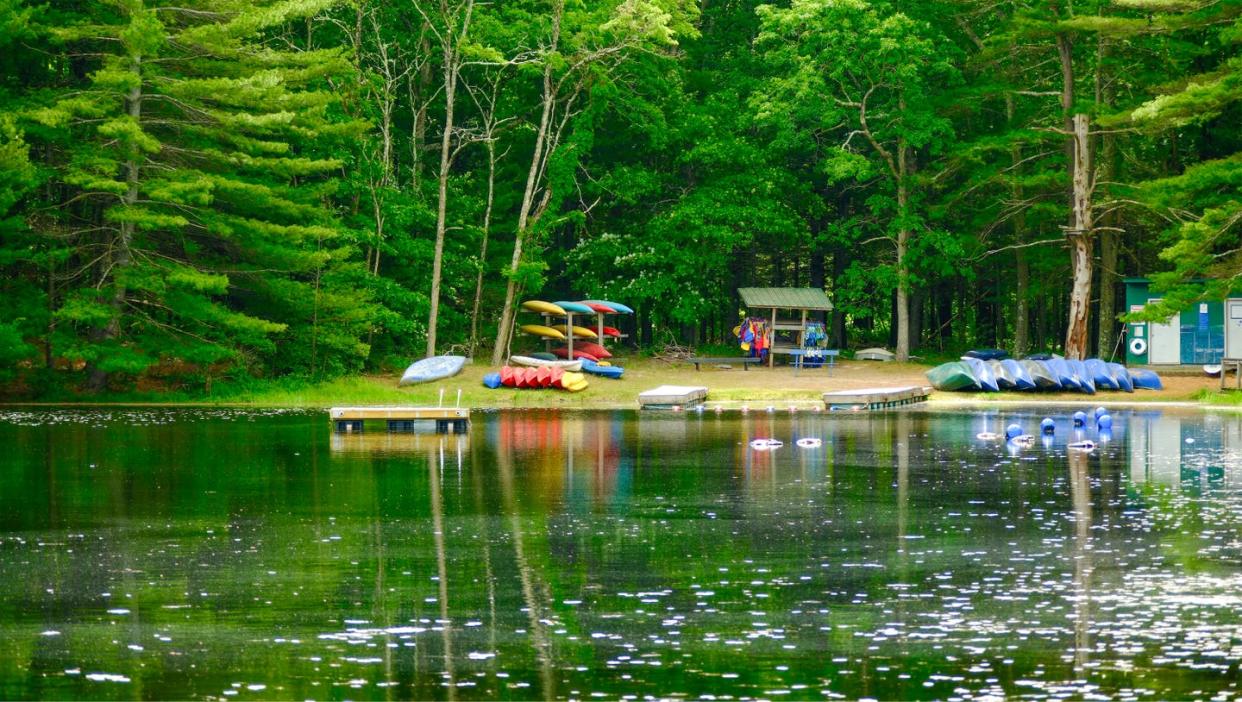

This is another way of saying, trans guys look like guys. Hundred and fifty of us, all united by one thing, sure, but no two the same, not at all. In the course of the weekend, I met accountants and veterans, DJs and lawyers, career men and happy-but-tired dads. There were men who bowed their heads to pray before they ate. There were some who attended breakout groups for specific minority identities. Some hung out in the “decompression space” reserved for men of color, a beautiful stone building overlooking the lake. Some seemed to spend a lot of their camp time in the gym or on the basketball court or soccer field. There were guys who strung up hammocks between trees or sat alone reading. There were guys who brought fishing gear or did yoga or walked around strumming an acoustic guitar.

I was especially aware of those men I’d see who, if I walked by them outside of this context, I admit with shame I would probably assume they were cis and straight and maybe the sort of cis straight person I need to fear. Here, none of us are having to do any of that wondering if we pass, wondering if we are safe, wondering if we are being clocked, wondering if we are man enough. Going down to the lake or back to my bunk, walking by guys on the trail, I felt myself meet their eyes. I felt myself say good morning, nod. I wondered when I had ever greeted strangers this way. Maybe when I was a kid, in my 300-person hometown, I thought.

Really: When had I ever felt so comfortable? What’s freed up inside, if we aren’t trapped in some closet or in some lie? Or if we aren’t defined by being “the only one” at our school or workplace or congregation or town? Many guys have attended one, two, three, four, even more camps prior and it’s not hard to understand why. Some dudes walked around with shirts unbuttoned or off. It was casual shirtless-ness. Other than at our own homes, or at a queer-friendly beach, where have we ever gotten to feel so safe? When do we get to be regular-ass men just walking around with shirts open or off, canoeing or sorting out the rules of pickleball? Where have we ever gotten to be so effortlessly understood?

There are generalizations I could make, our in-group stereotypes perhaps. At least ones I noted during this heavy concentration of this one sample size, which certainly wasn’t scientific and probably over-favored men in our thirties and twenties, and from Philadelphia and New York City and Boston. So take that for what you will. But that being said: Trans men have great style. We have fantastic tattoos. We have hilarious bumper stickers. I went around the pack of Subarus and Priuses and trucks parked around the bunks and out on the field and noted standouts: a smiling cartoon star that said FULL OF ANXIETY; one that said CHEWIE IS MY COPILOT; and multiple stickers making fun of the “don’t tread on me” snake. My favorite: a duck illustration that said ‘THROW BREAD ON ME’. I’d seen an actual DON’T TREAD ON ME flag flying during my drive between my home in rural New York and camp, as well as Trump flags of various sorts. The only mention of the Democrats was in a FUCK BIDEN banner (this was back in early June). Rocco had half-jokingly alluded in his announcements to the area beyond the camp boundaries as the “MAGA swamp”—as in, if we needed anything, don’t drive off into “the swamp,” please just ask a staffer for help.

Again—if I had to stereotype—trans men are funny. We are compassionate. We are warm-hearted and loving. We’ve had to be deliberate about a lot in our lives and also brave. Maybe, therefore, I think we tend to be open-minded and willing to have even hard conversations. I didn’t observe anybody having a problem with anybody else, at any point during the entire weekend, even if sometimes during group discussions people did respectfully disagree.

In the course of the weekend, I did observe lots of hugging, consensual. I did observe lots of crying—happy crying, bittersweet crying, overwhelmed crying. I did observe lots of rule-following and men going out of their way to help one another. Amongst trans men it’s a joke, how we are all the goodest boy, by which I think we mean, we sometime adopters of the masculine role are very aware of not wanting to become toxic men. I did observe lots of campers exchanging information and planning to see one another after these three days. One afternoon as a rainstorm passed, I did sit by watching as a group of men exchanged horror stories about their doctors while making friendship bracelets.

At the night-time pool party on the second evening, a sea of beautiful scars all around me, scars of every shape and color. Where had I ever seen so many scars? Some guys whose scars were near invisible; some who wore binders or shirts or robes. Also some who’ve not gotten surgeries. Some stayed clothed. Some men shivered by the fire pits and made s’mores.

Back in my bunk, I had nervously donned a pink bathing set—trunks with a matching short button-up shirt—an outfit I’ve seldom worn and certainly not off my own property. I was quite nervous. Pink is the sort of color I might like but still feel afraid to wear in the world, for fear of it encouraging misgendering. But this trunk and shirt set are also, frankly, super cute.

During my walk to the party, more than one guy said that he loved my outfit. A few asked where I got it. My confidence had soared.

Dipping my toes in the pool, I let my top surgery scars peek out of my opened shirt. I’ve never let my own chest be visible in public before.

Did this count as “in public”?

I studied the lifeguards, and the staff cleaning up from the BBQ we’d had. Everybody working the camp this weekend had all been vetted and trained, Rocco had explained, but it was also abundantly obvious, mostly because nobody stared, nobody gawked. The folks in the dining hall and helping with maintenance and overseeing the archery and kayaking and everything else, they weren’t one of us, sure, but they were also chill.

Us campers had been assured we would be understood and regarded here as men, by all—however not-on-Testosterone or not-passing we might look. I comment on this and commend these folks because it did give me hope, when it comes to that bigger question of whether everybody else could possibly calm down when it comes to the hating-trans-people thing that’s becoming so popular. Perhaps all it might take is experiencing—or even just imagining—us in a majority for a moment, feeling what it is to be the unusual one.

During free time one morning, a group milled about the archery area, taking turns with the two bows and three targets. The instructor would patiently stand by whoever was next to try, demonstrating where to put your feet and how to hold the bow. I had approached guessing I wouldn’t actually try it, just hide in my notebook and observe.

But I kept joking to myself: Maybe I should learn in case I ever need to hunt to survive. (I think I watched too many seasons of Alone during the pandemic’s height.) A few other guys noticed me lingering there and asked if I was going to give it a shot.

Rocco lingered around the archery area as well, making small talk. Other than meals when he took the mic and made announcements, Rocco mostly seemed to act like any other camper. He didn’t give the impression of being outdoorsy, really; like many city guys, he seemed freaked about ticks. If it was going to be that kind of survival camp, Rocco said, it was going to have to be facilitated by somebody else.

I let another dozen or so others approach and try archery before I finally said alright. I grasped the bow and figured out where to place the arrow, finding it less tricky than I’d feared. Before going to camp, my friend had said I’d be fine with archery because I’m strong. That it’s just about pulling it back, hard as I could.

I pulled back hard and released. The arrow hit with a pleasing THWACK on the bottom left-hand side of the target. I felt a rush of joy. I took up another arrow, and another, managing to hit the target several more times. I handed off the bow.

How rare, in the scheme of a trans life in 2024, to feel such intense and unbroken joy, as I did during the course of that weekend. Even though by its end I felt beyond socially drained. And even though, light sleeper and nervous pee-er that I am, my sleep was indeed pretty wretched and figuring out where to pee was a total ordeal. As I listened to Rocco say his farewells to us that final morning, I nonetheless felt a dread settle over me like a sky darkening before a great storm. It was a fear of re-entry into the real world. I wondered if I could handle it now.

Men who’d attended prior camps and such gatherings warned us first-timers it’d be a shock, going back to reality. Much as I missed home, much as I wanted to smother my face in my dog’s neck, I also never wanted to leave this Neverland. The rest of the world is just so unrelentingly terrible to us, these days, at least so it can feel to me. And yet so many of us have nonetheless chosen this life, feel we have no choice, in fact; again and again we choose this. We’ve chosen hormones despite health risks. We’ve chosen surgeries despite so much hassle and again potential danger—including death.

And how many of us, again, risk violence when we just walk down the block, or hop into the gas station to pay? Or what about the peril of loneliness itself and how it plagues us? My doctor these days is himself a trans man and he has said to me, for his lonely and /or remote patients (such as myself), he more or less wishes he could prescribe some dose of actual community at least once a year, like this camp (because the health risks of isolation are that real). How many campers shared stories this weekend of the people we’ve lost along the way. The families sure, and the partners, and the best friends and even entire friend groups. The jobs. Some lost their whole communities. Some men, especially those older than me, had sometimes begun transition as they had changed states and basically their whole identities.

Others, myself included, have performed the bizarre work of trying to come out despite having a life in progress already—a life whose nuances I do and don’t identify with now. Amongst fellow trans men, I didn’t need to explain how strange I feel all the time. How I am literally thirty-seven but also three-going-on-four (because of time on T) and also like eighteen or nineteen because in ways these all feel true. And, from what I can sort out, I appear like I’m in my twenties because that’s how strangers tend to treat me? I also feel a thousand, maybe because being alive and trans right now is exhausting. At camp I didn’t really need to explain to anybody how surreal it is to try to figure out what parts of my “self,” constructed through my first few decades remain authentic to me and which do not. What a balm it was for me to meet men who lived closeted lives much longer than even my own, especially for example those who came out past fifty.

Who am I now? Some guy. Blonde guy. Guy with a notebook. Guy with bed-head who needed a haircut but was too anxious in the lead-up to camp to get one. Guy who’s from Nor Cal originally and who despite being many years an expat is admittedly these days pretty woo-woo, and so, as I predicted, felt happiest during the morning meditation sessions. They were held in the open-air theater, the stage backgrounded by green leaves and the lake, and led by one of Rocco’s co-directors, Jay. Jay was extremely cool, almost distractingly so. I tried to focus on my breath and all that, clearing my chakras, communing with ancestors, frankly the stuff I do at home in my regular life. Finally: I had found the other guys who woke up too early and did this crap, wore chucks, lit incense. My people, I laughed to myself.

“Nervous guy!” the volunteer staffer from my COVID test smiled at me as we crossed one another on the trail. I chuckled hello in reply. He asked if I was less nervous and I said kinda. During a session one afternoon, I even gathered the nerve to share something extremely personal about myself, a story so painful I never talk about it with anyone except like my therapists and most trusted inner circle. Afterward, my bunkmate out on our porch called inside to me, “Sandy, come here!” He’d heard some of my story earlier and now told me what had happened to him, his tragedy an echo of mine. We hugged, and as I pulled away from the hug (nervous guy!), I felt him pull me back in tighter, basically saying, nope I’m gonna let you actually feel it. And I did.

When I got back to my house I showered for a long while and sobbed, I barely knew what about. But also I barely knew where to start, there were so many reasons I was sobbing. I sobbed about people I’d met, stories I’d heard, so beautiful, so utterly tragic. I sobbed about all the terrible ordeals men like us go through just to be.

I have contemplated that Peter Pan metaphor a lot, us as the Lost Boys. We were like expats from some country many of us have never before seen, I thought during the weekend, all come home. If that had been home, though, what did it mean to return to our lives, to the rest of the world, where we won’t share such visible and comforting brotherhood at all times? It was so beautiful, us all together, forging community, especially inter-generationally. And the power, too, of feeling myself placed into these greater narratives.

But what was that bigger story? Where is this all headed? One cannot help but wonder, I suppose, especially when our very precarious existence is so relentlessly, mercilessly attacked and politicized. I cannot help but wonder, are those of us who do not conform to the gender binary, that great powerful myth, are we some aberration, some little blip? Or are we—as it did truly feel that weekend—seeds now dispersed to the wind, impossible to contain?

I’d heard older guys—or those older in trans time—talk about this feeling of forgetting. As in, you hit a point where you just forget you’re trans. In the shower, I realized I had felt it. All those guys, all weekend, I had seen us, I had felt us, just as men. More importantly perhaps: I had felt myself as just a regular man.

At camp, beside the mess hall doors, there’d been two maps of the country and world, along which we’d been provided colorful post-it arrows and encouraged to write down where we were coming from. Afterwards, I kept picturing that rainbow smattering of post-its. I kept imagining one of those deserts that suddenly gets a big dump of rain and erupts into flowers. Which implies, really, that sure this looked like sand but there have been flowers here all along.

We are all over, is what those maps reminded me. We are here and we have been here — and dare I say, we will remain. Even if we may not be perceived wherever we are, and even though our existence will almost be guaranteed to be a hard one, we are here anyway. And maybe—if the rest of you are so lucky—someday we will all experience our glorious, full bloom.

You Might Also Like